Does Ashwagandha supplementation have a beneficial effect on the management of anxiety and stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Clinical Nutrition, School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 2 Department of Community Nutrition, School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 3 Department of Cellular and Molecular Nutrition, School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 4 Cognitive Neurology and Neuropsychiatry Division, Psychiatry Department, Roozbeh Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 5 Geriatric Department, Ziaeeian Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

- 6 Hemato-Oncology Ward, Taleghani Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science, Tehran, Iran.

- PMID: 36017529

- DOI: 10.1002/ptr.7598

Clinical trial studies revealed conflicting results on the effect of Ashwagandha extract on anxiety and stress. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the effect of Ashwagandha supplementation on anxiety as well as stress. A systematic search was performed in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar from inception until December 2021. We included randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that investigate the effect of Ashwagandha extract on anxiety and stress. The overall effect size was pooled by random-effects model and the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CIs) for outcomes were applied. Overall, 12 eligible papers with a total sample size of 1,002 participants and age range between 25 and 48 years were included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis. We found that Ashwagandha supplementation significantly reduced anxiety (SMD: -1.55, 95% CI: -2.37, -0.74; p = .005; I 2 = 93.8%) and stress level (SMD: -1.75; 95% CI: -2.29, -1.22; p = .005; I 2 = 83.1%) compared to the placebo. Additionally, the non-linear dose-response analysis indicated a favorable effect of Ashwagandha supplementation on anxiety until 12,000 mg/d and stress at dose of 300-600 mg/d. Finally, we identified that the certainty of the evidence was low for both outcomes. The current systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of RCTs revealed a beneficial effect in both stress and anxiety following Ashwagandha supplementation. However, further high-quality studies are needed to firmly establish the clinical efficacy of the plant.

Keywords: Ashwagandha; anxiety; meta-analysis; stress; systematic review.

© 2022 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Publication types

- Meta-Analysis

- Systematic Review

- Anxiety Disorders

- Anxiety* / drug therapy

- Dietary Supplements

- Middle Aged

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

- Ashwagandha

Phytotherapy Research

Subject Area and Category

- Pharmacology

John Wiley and Sons Ltd

Publication type

0951418X, 10991573

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

Evolution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- Editorial Board

- Instruction For Author

- Manscript Submission

International Journal Of

Phytotherapy Journal

e ISSN : 2249 - 7722

Print ISSN : 2249 - 7730

Subscriber Login!

A digital object identifier (DOI) is a unique alphanumeric string assigned by a registration agency

Abstracting and Indexing

CROSSREF, DOI, CAS, CASSI, Directory of Open Access Journal (DOAJ), Google Scholar etc.

Issn / e-Issn

An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) is an eight-digit serial number used to uniquely identify a serial publication.

International Journal of Phytotherapy is an international peer-reviewed multidisciplinary journal, scheduled to appear bi-annual and serve as a means for scientific information exchange in the international pharmaceutical forum The International Journal of Phytotherapy publishes original research articles; review articles; short communications; case reports; letters to the editors and rapid communications on the mechanisms of action of natural and chemical substances affecting biological systems.

The International standard serial number (ISSN) for International Journal of Phytotherapy is 2249 -7722.

International Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutics publishes original research papers, critical reviews and communications on the latest developments in the pharmaceutical sciences with strong emphasis on originality and scientific quality.

- Pharmacologists

- Pharmacognosist

- Phytochemist

- Pharmaceutical researchers

- Clinical pharmacist

International Journal of Phytotherapy exclusively covers the following fields of pharmacy: pharmacology and toxicology, experimental and clinical pharmacology, Pharmacognosy, Behavioral pharmacology, Neuropharmacology and analgesia, Cardiovascular pharmacology, Pulmonary, gastrointestinal and urogenital pharmacology, Endocrine pharmacology, Immunopharmacology and inflammation, and Molecular and cellular pharmacology and history of pharmacy. The primary criteria for acceptance and publication are scientific rigor and potential to advance the field. It is essential that authors prepare their manuscripts according to established specifications. Failure to follow them may result in papers being delayed or rejected. Therefore, contributors are strongly encouraged to read these instructions carefully before preparing a manuscript for submission. The manuscripts should be checked carefully for grammatical errors. All papers are subjected to blind peer review.

CROSSREF, DOI, CAS, CASSI (American Chemical Society), Directory of Open Access Journal (DOAJ), Google Scholar, Index Copernicus, ICAAP, Scientific commons, PSOAR, Open-J-Gate, Indian Citation Index (ICI), Index Medicus for WHO South-East Asia (IMSEAR), OAI, LOCKKS, OCLC (World Digital Collection Gateway), UIUC.

Scopus, Elsevier, EBSCO, EMBASE, SCI mago (SJR), Chemical Abstracts, Medline, Pubmed, Pubmed Central.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Clinical trials on pain lowering effect of ginger: A narrative review

Mariangela rondanelli, federica fossari, viviana vecchio, clara gasparri, gabriella peroni, daniele spadaccini, antonella riva, giovanna petrangolini, giancarlo iannello, mara nichetti, vittoria infantino, simone perna.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence , Vittoria Infantino, Department of Biomedical Science and Human Oncology, University of Bari, Azienda di Servizi alla Persona “Istituto Santa Margherita,” Pavia, 27100 Italy. Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Aug 28; Revised 2020 Apr 8; Accepted 2020 Apr 23; Issue date 2020 Nov.

This is an open access article under the terms of the http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Ginger has a pain‐reducing effect and it can modulate pain through various mechanisms: inhibition of prostaglandins via the COX and LOX‐pathways, antioxidant activity, inibition of the transcription factor nf–kB, or acting as agonist of vanilloid nociceptor. This narrative review summarizes the last 10‐year of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), in which ginger was traditionally used as a pain reliever for dysmenorrhea, delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), osteoarthritis (AO), chronic low back pain (CLBP), and migraine. Regarding dysmenorrhea, six eligible studies suggest a promising effect of oral ginger. As concerned with DOMS, the four eligible RCTs suggested a reduction of inflammation after oral and topical ginger administration. Regarding knee AO, nine RCTs agree in stating that oral and topical use of ginger seems to be effective against pain, while other did not find significant differences. One RCT considered the use of ginger in migraine and suggested its beneficial activity. Finally, one RCT evaluated the effects of Swedish massage with aromatic ginger oil on CLBP demonstrated a reduction in pain. The use of ginger for its pain lowering effect is safe and promising, even though more studies are needed to create a consensus about the dosage of ginger useful for long‐term therapy.

Keywords: chronic low back pain, dysmenorrhea, ginger, knee osteoarthritis, myalgia, pain

1. INTRODUCTION

Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae family), commonly known as ginger is a climbing perennial plant, indigenous to southeastern Asia. Ginger extract is a mixture of many biologically active constituents (Grzanna, Lindmark, & Frondoza, 2005 ). These compounds are numerous and vary depending on the place of origin and whether the rhizomes are fresh or dry (Ali, Blunden, Tanira, & Nemmar, 2008 ).

More than 400 chemical substances have been isolated and identified in ginger rhizomes extracts, and new ones are still being discovered (Charles, Garg, & Kumar, 2000 ; Jolad, Lantz, Solyom, & Chen, 2004 ; Ma, Jin, Yang, & Liu, 2004 ). At present, only a few of them have been evaluated for their pharmacological properties (Grzanna et al., 2005 ).

Carbohydrates, lipids, terpenes, and phenolic compounds are between the ones that already have been identified (Peter, 2016 ; Prasad & Tyagi, 2005 ). From the chemical point of view, isolated zingiber's principles are categorized into pungent and flavoring compounds. Pungent ones including gingerols, shogaols, zingerones, gingerdiols, gingerdione, and paradols are known to play a major role in various pharmacological actions (Jolad et al., 2004 ; Mashhadi et al., 2013 ; Peter, 2016 ; Prasad & Tyagi, 2005 ).

Patients suffering from diseases associated with chronic inflammation are turning to alternative compounds for relief of their symptoms or to take advantage of natural drug properties as prophylactic treatments. A complex interplay of inflammatory cells and a large range of chemical mediators are normally associated with the beginning of the inflammatory response, recruiting, and activating other immune cells to the site to subsequently solve it.

Several studies indicate that many different compounds in ginger are active in lowering chronic inflammatory diseases' symptoms:

Inhibition of prostaglandins via COX and LOX pathways

The traditional use of ginger infusions to alleviate rheumatism and arthritis have pushed researchers to investigate the anti‐inflammatory pathways of secondary metabolites of the plant (Baliga et al., 2011 ; Zahedi, Fathiazad, Khaki, & Ahmadnejad, 2012 ). Some authors attributed 6‐gingerol's anti‐inflammatory activity to the inhibition of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and LPS‐activated macrophages antigen presentation (Setty & Sigal, 2005 ; Tripathi, Tripathi, Kashyap, & Singh, 2007 ).

Dugasani et al. demonstrated that shogaols and all gingerols inhibit NO production in LPS‐stimulated RAW 264.7 cells in a dose‐dependent manner (Dugasani et al., 2010 ). Moreover, with their experiments they showed that stimulation of RAW 264.7 cells with LPS (1 g/ml) for 24 hr induced a dramatic increase in PGE2 production, four times the basal level (Dugasani et al., 2010 ).

Antioxidant activity on free radical scavenging cascade

Zingiber officinale active ingredients like gingerols, shogaols, zingerone, and so on exhibit antioxidant activity. Ginger inhibits an enzyme, namely xanthine oxidase, which is mainly involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Ahmad et al., 2015 ).

Inhibition of the transcription factor, nuclear NF‐kB

Grzanna and his group demonstrated for the first time that ginger inhibits the transcription factor nuclear NF‐kB (Grzanna et al., 2005 ). Nuclear NF‐kB is the principal regulator of pro‐inflammatory gene expression. Activated NF‐kB can be detected at sites of inflammation, and a link among NF‐kB activation, cytokine production, and inflammation is now generally accepted.

6‐gingerol displayed anti‐inflammatory activity by decreasing inducible NO synthase and TNF‐α expression through the suppression of I‐kBα phosphorylation, NF‐kB nuclear activation, and PKC‐α translocation. The compound was also found to control TLR‐mediated inflammatory responses. It inhibited NF‐kB activation and COX‐2 expression by inhibiting the LPS‐induced dimerization of TLR4 (Ahn, Lee, & Youn, 2009 ).

Vanilloid nociceptor agonist

Vanilloid nociceptor agonists are known to be potent analgesics. The moderate pungency of ginger has been attributed to the mixture of gingerol derivatives in the oleoresin fraction of processed ginger. Gingerols possess the vanillyl moiety which is considered important for activation of the VR1 receptor expressed in nociceptive sensory neurones (Dedov et al., 2002 ).

Dedov reported that gingerols act as agonists at vanilloid receptors suggesting an additional mechanism by which ginger may reduce inflammatory pain (Dedov et al., 2002 ). This finding has added gingerols and zingerone to the list of vanilloid receptor agonists.

Moreover, the presence of VR1 receptors throughout the brainstem (Mezey et al., 2000 ), where the nausea center is located, may conceivably be associated in part with the common use of ginger as antiemetic medicine (Dedov et al., 2002 ).

In summary, current evidence in vitro and in animal models demonstrated that many different compounds of ginger have been shown to posses antioxidative and anti‐inflammatory activities that may be active in lowering chronic inflammatory disease symptoms, in particular pain.

However, human studies that were carried out to assess whether oral or topic ginger has a positive effect by reducing pain are not numerous; furthermore, in these studies different dosages and methods of administration were used, as well as disparate products' formulations and different study designs.

Given this background, the aim of this narrative review was to assess the state of the art randomized clinical trials on pain lowering effect of ginger, considering the pathologies in which ginger is traditionally used in order to control pain, such as: dysmenorrhea, delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), knee osteoarthritis, chronic low back pain (CLBP), and migraine.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

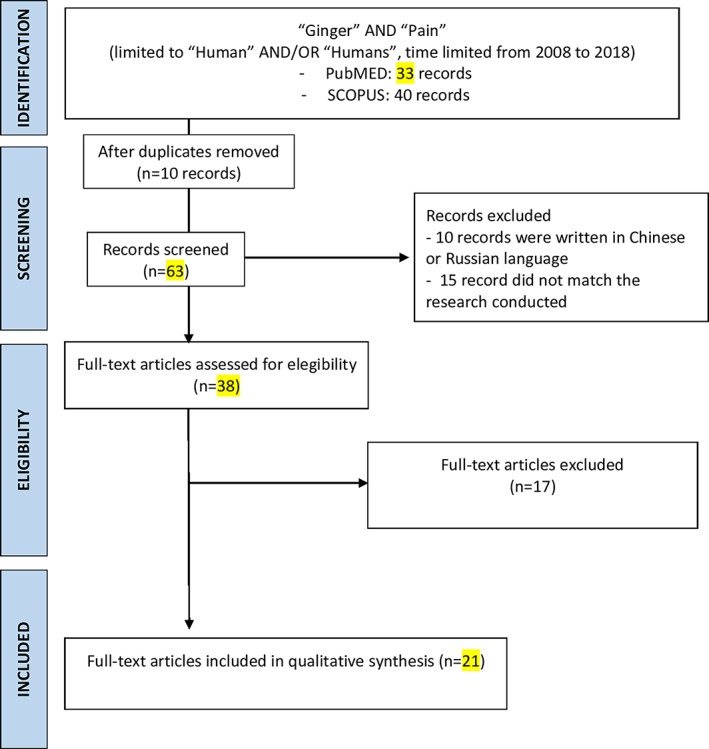

This narrative review was written after a PubMed and SCOPUS research performed with these keywords: “Ginger,” “pain” with the use of Boolean AND operator to establish the logical relation between them. The research was conducted by four skilled operators from July to September 2018 and followed Egger's criteria (Egger, Smith, & Altman, 2001 ; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman,, & PRISMA Group, 2009 ). The research was time limited (from 2008 to 2018) and restricted to English and humans randomized controlled trial (RCT). The keywords were pain, ginger, primary dysmenorrhea, DOMS, knee pain, osteoarthritis (AO), CLBP, and migraine. They were combined with “AND” to search related articles. Furthermore, we selected trials with oral ginger used as a primary, sole or combined therapy and compared with a placebo or active treatment in diseases. The analysis was carried out in the form of a narrative review (Figure 1 ).

Flow chart of literature research [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com ]

Standard datacoding tables were developed for extracting data from individual trials, key characteristics, and the level of evidence of each study (“Oxford Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine ‐ Levels of Evidence (March 2009)—CEBM,” 2009 ). The following data were extracted: participant characteristics, sample size, form and dosage of ginger, control group, assessment of adherence, outcome measures, methods for statistical analysis, study findings, and adverse events reported.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. dysmenorrhea.

This review summarizes evidence from six clinical trials (687 patients) evaluating the efficacy of oral ginger use for dysmenorrehea (Table 1 ). Among the six eligible studies, five were conducted in Iran (Jenabi, 2013 ; Kashefi et al., 2014 ; Ozgoli, Goli, & Simbar, 2009 ; Rahnama et al., 2012 ; Shirvani et al., 2017 ) and one in India (Halder, 2012 ). Participants were either college or high school students. Five of the six studies included only women with moderate to severe symptoms (Jenabi, 2013 ; Kashefi et al., 2014 ; Ozgoli, Goli, & Simbar, 2009 ; Rahnama et al., 2012 ). Five studies specified the inclusion of women with primary dysmenorrhea only, excluding women with secondary dysmenorrhea (Jenabi, 2013 ; Kashefi et al., 2014 ; Ozgoli, Goli, & Moattar, 2009 ; Rahnama et al., 2012 ; Shirvani et al., 2017 ); however, it is unclear how secondary dysmenorrhea was defined/diagnosed. Across the studies, the sample sizes of the ginger group ranged from N = 25 to N = 61. The daily dose of powdered ginger ranged from 750 to 2,000 mg. The most common duration and timing of ginger treatment was 3 days (the first 3 days of menstruation) (Halder, 2012 ; Jenabi, 2013 ; Ozgoli, Goli, & Simbar, 2009 ).

Summary of articles about effect of ginger on dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea is characterized by low abdominal or pelvic pain occurring before or during menstruation (Morrow & Naumburg, 2009 ). Better management of dysmenorrhea may not only improve women's quality of life, but also reduce their risk of developing future pain (Berkley & McAllister, 2011 ; Vincent et al., 2011 ). Dysmenorrhea is conventionally treated with nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) (Dawood, 2006 ), the efficacy of which are supported by research evidence (Wong, Farquhar, Roberts, & Proctor, 2009 ). However, NSAIDs and OCPs have limitations: some women with dysmenorrhea do not respond to NSAIDs or OCPs (with an estimated failure rate of >15% for NSAIDs) (Dawood, 2006 ); some cannot use these medications because of contraindications or adverse effects; some prefer not to use any medications. Therefore, investigation of complementary alternative treatments for dysmenorrhea is warranted. Ginger is one of the most commonly used natural products among women with dysmenorrhea. The exact mechanism of action of ginger in pain relief remains to be elucidated; however, some evidence suggests that the constituents of ginger have anti‐inflammatory and analgesic properties (Ali et al., 2008 ). Furthermore, preclinical research shows that ginger suppresses the synthesis of prostaglandin (through inhibition of cyclooxygenase) and leukotrienes, which are involved in dysmenorrhea pathogenesis (Dawood, 2006 ; Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC), 2013 ).

The available data suggest a promising pattern of oral ginger (750 to 2,000 mg for the first 3 days of menstruation) as a potentially effective treatment for pain in dysmenorrhea. All RCTs agree in demonstrating that ginger is more effective for pain relief than placebo, and no significant difference was found between ginger and NSAIDs (Halder, 2012 ; Jenabi, 2013 ; Kashefi et al., 2014 ; Ozgoli, Goli, & Moattar, 2009 ; Rahnama et al., 2012 ). These findings, however, need to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of studies, poor methodological quality, and high heterogeneity across the trials. Moreover, all of the included trials were conducted in Asia.

3.2. Delayed onset muscle soreness

This review summarizes evidence from four randomized clinical trials (194 subjects) evaluating the efficacy of oral or topic ginger use for DOMS (Table 2 ). Three RCT suggested an effective reduction of inflammation due to exercise‐induced muscle damage after daily consumption of 2 g of raw and heat‐treated ginger (Black et al., 2010 ; Manimmanakorn et al., 2016 ). A useful alternative seems to be the topical administration of Zingiber cassumunar in 14% concentration (Manimmanakorn et al., 2016 ). Finally, 4 g of ginger supplementation is the suggested dose to be used to accelerate recovery of muscle strength following intense exercise (Matsumura et al., 2015 ).

Summary of articles about effect of ginger on DOMS

DOMS indicated by muscle pain and tenderness typically occurs after a strenuous workout or undertaking unaccustomed exercise (Gulick & Kimura, 1996 ). The underlying causes of DOMS are related to exercise‐induced muscle damage, including sarcomere disruption, and the ensuing secondary inflammatory response , (Gleeson et al., 1995 ; Warren, Hayes, Lowe, Prior, & Armstrong, 1993 ). Inflammatory processes stimulate prostaglandin E2 release which sensitizes type III and IV pain afferents, and leukotrienes to attract neutrophils, which produce free radicals that further exacerbate muscle cell damage (Connolly, Sayeres, & McHugh, 2003 ). DOMS after eccentric exercise may result in reduction of muscle performance of athletes (Cheung, Hume, & Maxwell, 2003 ). Numerous methods to prevent and reduce DOMS have been suggested, including stretching exercises, massage, and nutritional supplementation. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been used in an attempt to reduce DOMS by reducing inflammation and pain and improving function.

Ginger and several of its constituents inhibit activity of COX‐1 and COX‐2, block leukotriene synthesis, and block the production of interleukins and tumor necrosis factor alpha in activated macrophages (Black et al., 2010 ). Thus, these antiinflammatory actions that may help reduce inflammation, such as exercise‐induced muscle damage, are recognized as a product of participating in unfamiliar or strenuous physical activity.

Given that ginger has antinflammatory and analgesic properties, it follows that it may be used to reduce the damage and consequent DOMS following high‐intensity exercise. (Black et al., 2010 ; Black & O'Connor, 2008 ).

3.3. Knee osteoarthritis

This review summarizes evidence from nine randomized clinical trials (964 patients) evaluating the efficacy of oral or topical ginger, sole or in combination with other botanicals, use for knee OA (Table 3 ). The three RCTs that considered the efficacy of oral ginger (powder supplementation of 1 g/day) on pain in knee OA demonstrated that efficacy of ginger on knee pain seemed not to have a unique position. Two studies suggested that the use of ginger in subjects with knee pain could decrease pain (Mozaffari‐Khosravi et al., 2016 ; Naderi et al., 2016 ) while other did not find significant differences (Naderi et al., 2016 ; Niempoog et al., 2012 ). The two RCT that assessed the efficacy of the topical use of ginger considered an aromatic essential oil (1% Zingiber officinale and 0.5% Citrus sinesis) (Yip & Tam, 2008 ) and 4% ginger gel (Niempoog et al., 2012 ) and agree in stating that the topical use of ginger seems to have potential as an alternative method for short‐term knee pain relief. Finally, all the four studies that considered the ginger supplementation in combination with other botanicals agree in demonstrating that these combinations are effective in order to decrease knee pain (Chopra et al., 2013 ; Drozdov et al., 2012 ; Nieman et al., 2013 ).

Summary of articles about effect of ginger on knee AO

Osteoarthritis Osteoarthritis (OA) is a joint disease characterized by degeneration of cartilage, pain, inflammation, impaired mobility, and dysfunction, especially in older populations (Heidari, 2011 ).

Current treatment for OA is palliative and is focused on pain relief and improving mobility, including a combination of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures. However, when these therapeutic treatments fail to improve symptoms, a variety of surgical interventions can be used (Haghighi, Tavalaei, & Owlia, 2006 ). With respect to some commonly‐used treatments, such as NSAIDs, there is increasing concern that long‐term consumption may cause gastrointestinal bleeding and cardiovascular risks, mainly hypertension and thrombotic events (Dingle, 1999 ; Mamdani, 2005 ). Thus, an interest in research has been conducted to find care treatments that have negligible adverse effects while offering significant improvements in the symptoms (Zakeri et al., 2011 ).

Ginger is thought to have anti‐inflammatory effects and may modulate the concentration and activity of inflammatory mediators in OA (Ahmad et al., 2015 ).

Only one RCT, that considered the efficacy of oral ginger (powder supplementation of 1 g/day) on pain in knee OA, did not find significant changes (Niempoog et al., 2012 ). These difference in the results between the study by Niempoog et al. and the study by Mozaffari‐Khosravi H, although the dosage used was the same (1 g/day), could be due to numerous reasons: the type of administration (non‐encapsulated powder vs. encapsulated powder), the duration of treatment (2 vs. 3 months), the parameters studied (symptoms and daily activities vs. inflammatory cytokines), number of patients evaluated (30 vs. 120 subjects) (Mozaffari‐Khosravi et al., 2016 ; Niempoog et al., 2012 ).

3.4. Chronic low back pain

As shown in Table 4 , one RCT was sourced using topical ginger. No RCT studies were found regarding oral ginger supplementation and pain in patients with low back pain.

Summary of articles about effect of ginger on migraine and low back pain

CLBP is defined as a chronic condition of lower back pain lasting for at least 3 months or longer (Andersson, 1999 ; Bogduk, 2004 ). Non‐pharmacologic interventions for CLBP are recommended when patients do not show improvement with standard treatment (Deyo, Mirza, & Martin, 2006 ).

Ginger has been used as an anti‐inflammatory and anti‐rheumatic for musculoskeletal pain (Altman & Marcussen, 2001 ; Therkleson, 2010 ). Although CLBP predominantly affects older people, only one study has specifically investigated the effects of Swedish massage with aromatic ginger oil in order to evaluate if improve the level of disability.

The objective of Sritoomma et al. was to investigate the effects of Swedish massage with aromatic ginger oil (SMGO) on CLBP and disability in older adults compared with traditional Thai massage (TTM). This study demonstrated that SMGO was more effective than TTM in reducing pain and improving disability at short‐ and long‐term assessments. It's important to note that there might be a lack of methodology in this study, because the difference might be due to the type of massage not to the use of ginger. Moreover, it is not clear if the benefit of low back pain is due to the massage and ability of the operator itself or the medical principle of ginger drug in the aromatic oil.

3.5. Migraine

One single RCT (Cady et al., 2011 ) on humans could be considered as the first effort to elucidate the use of ginger in this frequently disabling disease that is present in a large slice of the adult population. This multi‐center RCT on feverfew/ginger use seems to suggest an effective treatment to migraine.

Migraine is a complex neurological disease characterized by episodic periods of disabling physiological dysfunction typically recurring over decades of an individual's lifetime (Cady, Schreiber, & Farmer, 2004 ).

Treatment needs for migraine vary considerably from patient to patient and indeed, from attack to attack for the same patient. Pharmacologically, many over the counter and prescription products are effective on treatment in acute migraine (Monteith & Goadsby, 2011 ). Commonly employed acute treatments approved for migraine can be classified as over the counter products, such as acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine combination products and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory medications (Wenzel, Sarvis, & Krause, 2003 ), and prescription products, such as triptans and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatories (Ng‐Mak, Hu, Chen, & Ma, 2008 ). Various opioid and butalbital‐containing analgesics are also commonly prescribed, but most do not have Food and Drug Administration approval for migraine, and are generally avoided by physicians because of their propensity to produce medication overuse headache (Bigal, Rapoport, Sheftell, Tepper, & Lipton, 2004 ; Snow, Weiss, Wall, & Mottur‐Pilson, 2002 ).

The main limitation of this review is represented by searching just two databases and only English literature.

4. CONCLUSION

Current evidence in vitro and in animal models demonstrated that many different compounds of ginger have been shown to posses antioxidative and anti‐inflammatory activities that may be active in lowering chronic inflammatory disease symptoms, in particular, pain. This pain‐reducing effect of ginger has been modulated through various mechanisms: inibition of prostaglandins via the COX and LOX‐pathways, antioxidant activity, inibition of the transcription factor nf–kB, or acting as agonist of vanilloid nociceptor.

However, human studies that were carried out to assess whether oral or topic ginger has a positive effect by reducing pain are not numerous; furthermore, in these studies different dosages and methods of administration were used, as well as different study designs.

This narrative review summarizes the last 10‐year of RCT, in which ginger was traditionally used as a pain reliever for dysmenorrhea, DOMS, knee AO, CLBP, and migraine.

Regarding dysmenorrhea, six eligible studies suggest a promising effect of oral ginger. As concerns DOMS, the four eligible RCTs suggested a reduction of inflammation after oral and topical ginger administration. Regarding knee AO, eight RCTs agree in stating that oral and topical use of ginger seems to be effective against pain, while others did not find significant differences. One RCT considered the use of ginger in migraine and suggested its beneficial activity. Finally, one RCT evaluated the effects of Swedish massage with aromatic ginger oil on CLBP demonstrated a reduction in pain.

The most of the included trials were conducted in Asia. Pharmacogenetics and outcome expectancy regarding ginger intervention could differ across cultures and ethnicities, and therefore, it is necessary to confirm the promising effects in the worldwide population.

In conclusion, the use of ginger for its pain lowering effect is safe and promising, even if more studies are needed to create a consensus about the amount of ginger useful for long‐term therapy. The positive health benefits need to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of studies, poor methodological quality, and high heterogeneity across the trials. Therefore, new studies, possibly multi‐center RCT in different continents, with an adequate number of patients and with standardized ginger formulations, are necessary to confirm the results of this review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rondanelli M, Fossari F, Vecchio V, et al. Clinical trials on pain lowering effect of ginger: A narrative review. Phytotherapy Research. 2020;34:2843–2856. 10.1002/ptr.6730

- Ahmad, B. , Rehman, M. U. , Amin, I. , Arif, A. , Rasool, S. , Bhat, S. A. , … Mir, M. U. R. (2015). A review on pharmacological properties of zingerone (4‐[4‐Hydroxy‐3‐methoxyphenyl]‐2‐butanone). The Scientific World Journal, 1–6. 10.1155/2015/816364 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahn, S. I. , Lee, J. K. , & Youn, H. S. (2009). Inhibition of homodimerization of toll‐like receptor 4 by 6‐shogaol. Molecules and Cells, 27(2), 211–215. 10.1007/s10059-009-0026-y [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ali, B. H. , Blunden, G. , Tanira, M. O. , & Nemmar, A. (2008). Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger ( Zingiber officinale Roscoe): A review of recent research. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 46(2), 409–420. 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.085 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Altman, R. D. , & Marcussen, K. C. (2001). Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 44(11), 2531–2538. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200111)44:11<2531::aid-art433>3.0.co;2-j [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Andersson, G. B. (1999). Epidemiological features of chronic low‐back pain. The Lancet, 354(9178), 581–585. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baliga, M. S. , Haniadka, R. , Pereira, M. M. , D'Souza, J. J. , Pallaty, P. L. , Bhat, H. P. , & Popuri, S. (2011). Update on the chemopreventive effects of ginger and its phytochemicals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 51(6), 499–523. 10.1080/10408391003698669 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berkley, K. J. , & McAllister, S. L. (2011). Don't dismiss dysmenorrhea! Pain, 152(9), 1940–1941. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.013 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bigal, M. , Rapoport, A. , Sheftell, F. , Tepper, S. , & Lipton, R. (2004). Transformed migraine and medication overuse in a tertiary headache centre—Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Cephalalgia, 24(6), 483–490. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00691.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black, C. D. , Herring, M. P. , Hurley, D. J. , & O'Connor, P. J. (2010). Ginger ( Zingiber officinale ) reduces muscle pain caused by eccentric exercise. The Journal of Pain, 11(9), 894–903. 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.12.013 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black, C. D. , & O'Connor, P. J. (2008). Acute effects of dietary ginger on quadriceps muscle pain during moderate‐intensity cycling exercise. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 18(6), 653–664. 10.1123/ijsnem.18.6.653 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bogduk, N. (2004). Management of LBP Bogduk 2004. Medical Journal of Australia, 180, 79–83. 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181caa9b6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cady, R. K. , Goldstein, J. , Nett, R. , Mitchell, R. , Beach, M. E. , & Browning, R. (2011). A double‐blind placebo‐controlled pilot study of sublingual feverfew and ginger (LipiGesic™M) in the treatment of migraine. Headache, 51(7), 1078–1086. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01910.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cady, R. K. , Schreiber, C. P. , & Farmer, K. U. (2004). Understanding the patient with migraine: The evolution from episodic headache to chronic neurologic disease. A proposed classification of patients with headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 44(5), 426–435. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04094.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Charles, R. , Garg, S. N. , & Kumar, S. (2000). New gingerdione from the rhizomes of Zingiber officinale . Fitoterapia, 71(6), 716–718. 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00215-X [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheung, K. , Hume, P. A. , & Maxwell, L. (2003). Delayed onset muscle soreness. Sports Medicine, 33(2), 145–164. 10.2165/00007256-200333020-00005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chopra, A. , Saluja, M. , Tillu, G. , Sarmukkaddam, S. , Venugopalan, A. , Narsimulu, G. , … Patwardhan, B. (2013). Ayurvedic medicine offers a good alternative to glucosamine and celecoxib in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, double‐blind, controlled equivalence drug trial. Rheumatology, 52(8), 1408–1417. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes414 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connolly, D. , Sayeres, S. , & McHugh, M. (2003). Treatment and prevention of delayed onset muscle soreness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 17, 197–208. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dawood, M. Y. (2006). Clinical expert series primary dysmenorrhea advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 108, 428–441. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dedov, V. N. , Tran, V. H. , Duke, C. C. , Connor, M. , Christie, M. J. , Mandadi, S. , & Roufogalis, B. D. (2002). Gingerols: A novel class of vanilloid receptor (VR1) agonists. British Journal of Pharmacology, 137(6), 793–798. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704925 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deyo, R. , Mirza, S. , & Martin, B. (2006). Back pain prevalence and visit rates: Estimates from U.S. National Surveys, 2002. Spine, 31(23), 2724–2727. 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dingle, J. T. (1999). The effects of NSAID on the matrix of human articular cartilages. Zeitschrift fur Rheumatologie, 58, 125–129. 10.1007/s003930050161 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drozdov, V. N. , Kim, V. A. , Tkachenko, E. V. , & Varvanina, G. G. (2012). Influence of a specific ginger combination on gastropathy conditions in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(6), 583–588. 10.1089/acm.2011.0202 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dugasani, S. , Pichika, M. R. , Nadarajah, V. D. , Balijepalli, M. K. , Tandra, S. , & Korlakunta, J. N. (2010). Comparative antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory effects of [6]‐gingerol, [8]‐gingerol, [10]‐gingerol and [6]‐shogaol. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 127(2), 515–520. 10.1016/j.jep.2009.10.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger, M. , Smith, G. D. , & Altman, D. G. (2001). Systematic reviews in health care: Meta‐analysis in context, London, England: BMJ Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gleeson, M. , Almey, J. , Brooks, S. , Cave, R. , Lewis, A. , & Griffiths, H. (1995). Haematological and acute‐phase responses associated with delayed‐onset muscle soreness in humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 71(2–3), 137–142. 10.1007/BF00854970 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grzanna, R. , Lindmark, L. , & Frondoza, C. G. (2005). Ginger—An herbal medicinal product with broad anti‐inflammatory actions. Journal of Medicinal Food, 8(2), 125–132. 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.125 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gulick, D. , & Kimura, I. (1996). Delayed onset muscle soreness: What is it and how do we treat it? Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 5(3), 234–243 Retrieved from https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsr/5/3/article-p234.xml [ Google Scholar ]

- Haghighi, A. , Tavalaei, N. , & Owlia, M. B. (2006). Effects of ginger on primary knee osteoarthritis. Indian Journal of Rheumatology, 1(1), 3–7. 10.1016/S0973-3698(10)60514-6 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Halder, A. (2012). Effect of progressive muscle relaxation versus intake of ginger powder on dysmenorrhoea amongst the nursing students in Pune. The Nursing Journal of India, 103(4), 152–156. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heidari, B. (2011). Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian Journal of Internal Medicine, 2(2), 205–212. 10.1103/PhysRevD.86.056008 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). (2013). Herbal medicine: Summary for the public. What are the HMPC conclusions on its medicinal uses?, 44, 4–6. Retrieved from www.ema.europa.eu

- Jenabi, E. (2013). The effect of ginger for relieving of primary dysmenorrhoea. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 63(1), 8–10. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jolad, S. , Lantz, R. , Solyom, A. , & Chen, G. (2004). Fresh organically grown ginger ( Zingiber officinale ): Composition and effects on LPS‐induced PGE2 production. Phytochemistry, 65(13), 1937–1954. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.06.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kashefi, F. , Khajehei, M. , Tabatabaeichehr, M. , Alavinia, M. , & Asili, J. (2014). Comparison of the effect of ginger and zinc sulfate on primary dysmenorrhea: A placebo‐controlled randomized trial. Pain Management Nursing, 15(4), 826–833. 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.09.001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ma, J. , Jin, X. , Yang, L. , & Liu, Z. L. (2004). Diarylheptanoids from the rhizomes of Zingiber officinale . Phytochemistry, 65(8), 1137–1143. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mamdani, M. (2005). The changing landscape for COX‐2 inhibitors: A summary of recent events. Healthcare Quarterly, 8(2), 24–26. 10.12927/hcq..17052 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manimmanakorn, N. , Manimmanakorn, A. , Boobphachart, D. , Thuwakum, W. , Laupattarakasem, W. , & Hamlin, M. J. (2016). Effects of Zingiber cassumunar (Plai cream) in the treatment of delayed onset muscle soreness. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 14(2), 114–120. 10.1016/S2095-4964(16)60243-1 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mashhadi, N. S. , Ghiasvand, R. , Askari, G. , Feizi, A. , Hariri, M. , Darvishi, L. , … Hajishafiee, M. (2013). Influence of ginger and cinnamon intake on inflammation and muscle soreness endued by exercise in Iranian female athletes. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4(Suppl 1), S11–S15. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23717759 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsumura, M. D. , Zavorsky, G. S. , & Smoliga, J. M. (2015). The effects of pre‐exercise ginger supplementation on muscle damage and delayed onset muscle soreness. Phytotherapy Research, 29(6), 887–893. 10.1002/ptr.5328 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mezey, E. , Toth, Z. E. , Cortright, D. N. , Arzubi, M. K. , Krause, J. E. , Elde, R. , … Szallasi, A. (2000). Distribution of mRNA for vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (VR1), and VR1‐like immunoreactivity, in the central nervous system of the rat and human. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(7), 3655–3660. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3655 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. , & PRISMA Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Monteith, T. S. , & Goadsby, P. J. (2011). Acute migraine therapy: New drugs and new approaches. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 13(1), 1–14. 10.1007/s11940-010-0105-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morrow, C. , & Naumburg, E. H. (2009). Dysmenorrhea. Primary Care; Clinics in Office Practice, 36, 19–32. 10.1016/j.pop.2008.10.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mozaffari‐Khosravi, H. , Naderi, Z. , Dehghan, A. , Nadjarzadeh, A. , & Fallah Huseini, H. (2016). Effect of ginger supplementation on proinflammatory cytokines in older patients with osteoarthritis: Outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 35(3), 209–218. 10.1080/21551197.2016.1206762 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Naderi, Z. , Mozaffari‐Khosravi, H. , Dehghan, A. , Nadjarzadeh, A. , & Huseini, H. F. (2016). Effect of ginger powder supplementation on nitric oxide and C‐reactive protein in elderly knee osteoarthritis patients: A 12‐week double‐blind randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 6(3), 199–203. 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.12.007 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng‐Mak, D. S. , Hu, X. H. , Chen, Y.‐T. , & Ma, L. (2008). Acute migraine treatment with oral triptans and NSAIDs in a managed care population. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 48(8), 1176–1185. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01055.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nieman, D. C. , Shanely, R. A. , Luo, B. , Dew, D. , Meaney, M. P. , & Sha, W. (2013). A commercialized dietary supplement alleviates joint pain in community adults: A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled community trial. Nutrition Journal, 12(1), 1–9. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-154 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Niempoog, S. , Siriarchavatana, P. , & Kajsongkram, T. (2012). The efficacy of plygersic gel for use in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet Thangphaet, 95(Suppl 1), S113–S119. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23451449 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine ‐ Levels of Evidence (March 2009) ‐ CEBM . 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2019, from https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford‐centre‐evidence‐based‐medicine‐levels‐evidence‐march‐2009/

- Ozgoli, G. , Goli, M. , & Moattar, F. (2009). Comparison of effects of ginger, Mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(2), 129–132. 10.1089/acm.2008.0311 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ozgoli, G. , Goli, M. , & Simbar, M. (2009). Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(3), 243–246. 10.1089/acm.2008.0406 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peter, K. V. (2016). Ginger. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 10.1201/9781420023367 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prasad, S. , & Tyagi, A. (2005). Ginger and its constituents: Role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology Research, 2015, 1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rahnama, P. , Montazeri, A. , Huseini, H. F. , Kianbakht, S. , & Naseri, M. (2012). Effect of Zingiber officinale R. rhizomes (ginger) on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: A placebo randomized trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 12(1), 92 10.1186/1472-6882-12-92 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Setty, A. R. , & Sigal, L. H. (2005). Herbal medications commonly used in the practice of rheumatology: Mechanisms of action, efficacy, and side effects. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 34(6), 773–784. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.011 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shirvani, M. A. , Motahari‐Tabari, N. , & Alipour, A. (2017). Use of ginger versus stretching exercises for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 15(4), 295–301. 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60348-0 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snow, V. , Weiss, K. , Wall, E. M. , & Mottur‐Pilson, C. (2002). Pharmacologic management of acute attacks of migraine and prevention of migraine headache. Annals of Internal Medicine, 137, 840–849. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sritoomma, N. , Moyle, W. , Cooke, M. , & O’Dwyer, S. (2014). The effectiveness of Swedish massage with aromatic ginger oil in treating chronic low back pain in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 22(1), 26–33. 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Therkleson, T. (2010). Ginger compress therapy for adults with osteoarthritis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(10), 2225–2233. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05355.x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tripathi, P. , Tripathi, P. , Kashyap, L. , & Singh, V. (2007). The role of nitric oxide in inflammatory reactions. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology, 51, 443–452. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00329.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vincent, K. , Warnaby, C. , Stagg, C. J. , Moore, J. , Kennedy, S. , & Tracey, I. (2011). Dysmenorrhoea is associated with central changes in otherwise healthy women. Pain, 152(9), 1966–1975. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.03.029 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Warren, G. L. , Hayes, D. A. , Lowe, D. A. , Prior, B. M. , & Armstrong, R. B. (1993). Materials fatigue initiates eccentric contraction‐induced injury in rat soleus muscle. The Journal of Physiology, 464, 477–489 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8229814 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wenzel, R. G. , Sarvis, C. A. , & Krause, M. L. (2003). Over‐the‐counter drugs for acute migraine attacks: Literature review and recommendations. Pharmacotherapy, 23(4), 494–505. 10.1592/phco.23.4.494.32124 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong, C. L. , Farquhar, C. , Roberts, H. , & Proctor, M. (2009). Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4), CD002120. 10.1002/14651858.CD002120.pub3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yip, Y. B. , & Tam, A. C. Y. (2008). An experimental study on the effectiveness of massage with aromatic ginger and orange essential oil for moderate‐to‐severe knee pain among the elderly in Hong Kong. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 16(3), 131–138. 10.1016/j.ctim.2007.12.003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahedi, A. , Fathiazad, F. , Khaki, A. , & Ahmadnejad, B. (2012). Protective effect of ginger on gentamicin‐induced apoptosis in testis of rats. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2(2), 197–200. 10.5681/apb.2012.030 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zakeri, Z. , Izadi, S. , Bari, Z. , Soltani, F. , Narouie, B. , & Ghasemi‐Rad, M. (2011). Evaluating the effects of ginger extract on knee pain, stiffness and difficulty in patients with knee AO. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research, 5(15), 3375–3379. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zahmatkash, M. , & Vafaeenasab, M.R. (2011). Comparing analgesic effects of a topical herbal mixed medicine with salicylate in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Pakistan Journal of Biological Science, 14(13), 715–719. 10.3923/pjbs.2011.715.719 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.4 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Phytotherapy Research is an international pharmacological journal providing a pioneering resource for biochemists, pharmacologists, and toxicologists. We publish original medicinal plant research that advances knowledge and understanding. Our key areas of interest are pharmacology, toxicology, and the clinical applications of herbs and natural products in medicine.

Phytotherapy Research is a monthly, pharmacologically-oriented international journal for the publication of original research papers (experimental and clinical), review articles (including systematic reviews and meta-analyses), letters on medicinal plant research. Key areas of interest are pharmacology, toxicology, and the clinical applications ...

Phytotherapy Research is a medicinal chemistry journal for biochemists, pharmacologists, & toxicologists interested in medicinal plant research & clinical applications.

Phytotherapy Research is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing original research papers, short communications, reviews, and letters on medicinal plant research. Key areas of interest are pharmacology, toxicology, and the clinical applications of herbs and natural products in medicine, from case histories to full clinical trials, including studies of herb-drug interactions and ...

Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2014;28(5):692-698. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5044. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ] Brooks NA, Wilcox G, Walker KZ, Ashton JF, Cox MB, Stojanovska L. Beneficial effects of Lepidium meyenii (Maca) on psychological symptoms and measures of sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women are not related to estrogen or ...

Clinical trial studies revealed conflicting results on the effect of Ashwagandha extract on anxiety and stress. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the effect of Ashwagandha supplementation on anxiety as well as stress. A systematic search was performed in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Google Scholar from …

Phytotherapy Research is a monthly, international journal for the publication of original research papers, short communications, reviews and letters on medicinal plant research. Key areas of interest are pharmacology, toxicology, and the clinical applications of herbs and natural products in medicine, from case histories to full clinical trials ...

International Journal of Phytotherapy is an international peer-reviewed multidisciplinary journal, scheduled to appear bi-annual and serve as a means for scientific information exchange in the international pharmaceutical forum The International Journal of Phytotherapy publishes original research articles; review articles; short communications; case reports; letters to the editors and rapid ...

Phytotherapy Research publishes original research papers, reviews and letters on the pharmacology, toxicology and clinical applications of herbs and natural products. It covers herb-drug interactions, safety, food ingredients and plant extracts.

Flow chart of literature research [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]. Standard datacoding tables were developed for extracting data from individual trials, key characteristics, and the level of evidence of each study ("Oxford Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine ‐ Levels of Evidence (March 2009)—CEBM," 2009).The following data were extracted: participant ...