Humphrey Fellows at Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication – ASU

Exploring the world through servant leadership

From Nepal to California: A Fight Against Caste-Based Discrimination

- CevherShare

<Prem Pariyar>

At school, friends and teachers did not eat food or drink water touched by Prem Pariyar. He and his family were also barred from worshiping at the temple.

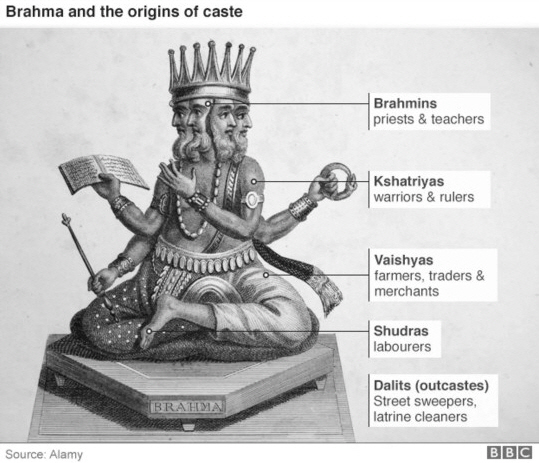

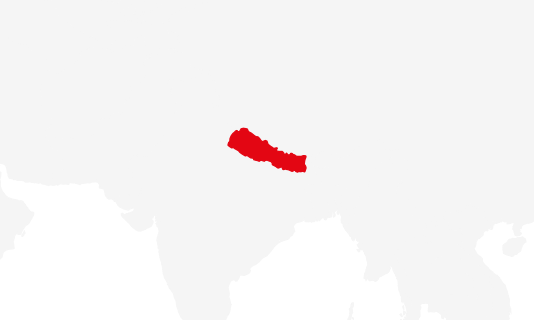

In Nepal, more than 400,000 individuals out of the country’s 30 million population belong to a community known as the untouchables. Members of this community, like Prem Pariyar, identify themselves as Dalits, which translates to ‘the oppressed.’

Raised within this caste system, Prem encountered discrimination at every stage of his life. Residing in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital, his family was subjected to physical assaults when accessing the same public water source as their neighbors. “Despite displacement and violence, we couldn’t find justice. This prompted my decision to leave Nepal for the U.S.,” he recalled.

Beyond Nepal, discrimination resonates across the South Asian diaspora worldwide, notably affecting South Asian Dalit communities in the U.S. This has prompted universities to revise non-discrimination policies, and cities like Seattle, Washington, and Fresno, California to amend their regulations. These efforts have further galvanized California’s senate and assembly to amend some state laws but faced a setback with the Governor’s veto. This obstacle not only poses a challenge to the Dalit rights movement but also highlights power struggles, revealing tensions between the upper-caste elite and the marginalized Dalit community.

Upon arriving in the U.S. to escape caste-based discrimination, Prem discovered that prejudice had followed him. In California, he encountered exclusion within the Nepali diaspora. “At a party, I was segregated and made to wait for food instead of serving myself,” he said. “I was shocked to see how this shadowed me here too, where I expected only educated individuals concerned with human rights. It shattered my illusion.”

One day, as he waited for the light rail, he struck up a conversation with two speaking Nepali individuals. Upon introducing himself as a graduate student in the social work department at California State University, East Bay, the initial exchange was amiable. However, when asked for his surname, a common practice in South Asia to discern caste affiliations, and disclosed the name as ‘Pariyar,’ the mood changed.

Recalling his newly met compatriots’ reaction, he said the two individuals gave him a thorough examination from head to toe. “I sensed in their scrutiny a question of, ‘How could you come here to study in the same university as we are studying?’ The moment was deeply embarrassing.”

This discrimination prompted him to seek legal mechanisms within the university. However, he found no specific mechanism to address caste-based discrimination, even though procedures and remedies existed for discrimination based on race, disability, sexual orientation, and gender.

In collaboration with a professor from the social work department, he developed various strategies to address the issue. The professor introduced him to Equality Lab, a Dalit feminist-led civil rights NGO that combats caste-based discrimination in the U.S.

This activism evolved into a more structured approach as Equality Lab developed its engagement with the Department of Social Work. Initially, the department revised its mission statement to include caste as a protected category, alongside race, ethnicity, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, immigration status, religion, and other forms of social injustice in its non-discrimination policy.

Subsequently, the issue was addressed by the academic senate’s faculty diversity and equity committee at CSU East Bay. A resolution was passed to incorporate caste as a protected category in the university’s non-discrimination policy .

This initiative expanded to the CSU system, one of the largest public university systems in the country with 23 campuses, which also included caste as a protected category in its non-discrimination policy.

Before this development, Brandeis University had already banned caste-based discrimination, becoming the first U.S. university to do so. Harvard University , the University of California, Davis, and Brown University followed similar prohibitions. Under the revised policy, students and staff can now file complaints if they experience discrimination or harassment based on their perceived castes, and these complaints may trigger formal investigations.

“We engaged in extensive lobbying efforts with politicians and university leaders, sharing personal testimonies on caste discrimination, organizing grassroots initiatives, and seeking advice from legal experts,” an Equality Lab spokesperson stated in an email interview. “As a result, we achieved such policy reform within universities.”

Following the progress at universities, the movement transitioned to cities. In February 2023, the Seattle City Council passed a resolution to include caste as a protected category in the city’s anti-discrimination laws , marking Seattle as the first city to enact such laws in the U.S. Subsequently, Fresno, California, became the second U.S. city to explicitly prohibit caste discrimination when the City Council unanimously voted in September 2023 to add ‘caste’ and ‘indigeneity’ as new protected categories in its municipal code.

In California, the Dalit rights movement gained momentum following a lawsuit filed by the California Civil Rights Department (formerly the Department of Fair Employment and Housing) against Cisco, the Silicon Valley tech giant, and two of its engineers in 2020. The lawsuit alleged caste-based discrimination against an employee by Cisco supervisors and engineers. Cisco denied the allegations. Later, the Civil Rights Department voluntarily dropped the case.

Despite the prohibition of caste-based discrimination in Nepal during the 1960s and in India since the 1950s, the issue remains a significant societal challenge. This system not only segregates people based on their caste hierarchy but also limits their employment opportunities. Initially, Dalit families were denied education, which affected their access to employment, healthcare, and political empowerment.

Following the restoration of democracy in Nepal and the end of British colonial rule in India, governments introduced laws to curb discrimination and implemented reservation policies to promote education and employment among Dalits.

Historically, migration to Western countries has been dominated by individuals from the upper echelons of the caste system who had access to education and job prospects. However, with government initiatives promoting Dalit education and employment, members of the Dalit community have begun migrating to the West.

According to Equality Lab’s 2018 report , “Caste in the United States: A Survey of Caste Among South Asian Americans,” a significant portion of Dalit migration to America occurred within the last decade. In contrast, upper-caste individuals who migrated to America did so primarily 25 to 50 years ago. Consequently, instances of discrimination and social power struggles have emerged in the US.

According to the Equality Lab’s survey report, one in every three Dalit students has reported experiencing discrimination during their education. Additionally, two out of three Dalits have reported unfair treatment in their workplaces, with 60% of Dalits stating they have encountered caste-based derogatory jokes or comments.

California, home to a large number of South Asian immigrants, including those from the Dalit community, has recently seen backlash within the diaspora regarding caste-based discrimination. State Sen. Aisha Wahab, D-Hayward, sought to curb such discrimination.

In Feb 2023, she introduced Senate Bill 403 , which proposed adding caste to the list of non-discriminatory grounds in the Fair Employment and Housing Act, the Unruh Civil Rights Act, and the Education Code.

The Judiciary Committee approved the bill in April, marking the first step in the legislative process. The Senate passed the bill in May with a 34-1 vote, and the Assembly followed suit in August with a 31-5 vote.

In September, the Senate sent the bill to Gov. Gavin Newsom for his signature. However, Newsom vetoed the bill on Oct. 7, citing existing laws that already prohibit discrimination based on ancestry, thus deeming the bill unnecessary. Had he signed it, California would have become the first state to explicitly ban caste-based discrimination.

Sen. Wahab didn’t provide comments; however, after the bill was vetoed, she stated in her public remarks that she “will continue to fight to balance power and support vulnerable Californians.”

“I believe our laws need to be more explicit, especially in times when we see civil rights being eroded across the country. We cannot take anything for granted,” she wrote .

In the aftermath of legal reform efforts in California, a backlash has surfaced. A segment of Hindu Americans argue that these laws disproportionately target their community. After the California State University (CSU) board of trustees approved the policy, approximately 80 CSU faculty members criticized it. They signed a petition against the reform initiatives, expressing concern that the new policy would apply solely to South Asians. They argue that including caste in the non-discrimination policy would unlawfully single out Indians and South Asians.

However, some people see this as an indication of the increasing influence of Hindu nationalism in the United States. They associate this directly with the Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an Indian Hindu nationalist organization that shares ideological similarities with the governing party of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“This path isn’t easy, but we know that none of the civil rights laws have been passed easily,” Prem said. “Our fight is for equality. It shouldn’t have taken this long.”

( The story was produced as part of the Humphrey Seminar’s assignment, and some paragraphs were translated from Nepali to English using the AI assistant Claude.)

Related Posts

Young Africans on a Mission: Chasing International Scholarships, Facing Systemic Hurdles

May 24, 2024 May 24, 2024

A Phoenix Manual for International Fellows

April 28, 2024

Sedona’s vortex: Believe or not to believe

April 22, 2024 April 23, 2024

About Tufan Neupane

The Legacy of Caste Discrimination in Nepal’s Criminal Justice System

Updated: Jan 15, 2021

By Ajay Shankar Jha Rupesh, ILF Nepal Country Representative and Executive Director of PDS-Nepal

The recent murder of a young Dalit man, Nawaraj BK, and his five friends was a tragic reminder for the world that caste discrimination is still very much alive in Nepal. The murders sparked protests around the country calling for justice, and the issue goes far beyond this act of violence. Discrimination against people considered lower-caste has all too often meant that they are ignored as victims of crime and their abusers enjoy impunity. At the same time, like other marginalized communities , people considered lower-caste are disproportionately arrested, convicted, and mistreated in the criminal justice system. Dalits are the first punished and the last protected.

The caste system has traditionally defined social order in Nepal: Dalits, who make up between 13 and 20 percent of the population , occupy the lowest rung of this social order. Historically, this meant that Dalit men, women, and children were considered “untouchable” and were denied education, healthcare, public amenities, and economic opportunities. This discrimination has locked Dalits into a continued cycle of exclusion, poverty and violence for centuries.

The caste system in Nepal was formally declared unconstitutional in 1951 , and caste-based discrimination was criminalized in 2011 , but the legacy of systemic discrimination lives on today. Poverty rates are much higher in Dalit communities and education rates are lower compared to other groups. In addition, there are very few Dalit leaders in government: as of 2018, Dalits made up only around 8% of parliament .

This social structure is reflected in Nepal’s criminal justice system. While marginalized people are underrepresented in the police force , courts , and other powerful institutions, they are overrepresented in the prison population. While statistics about Nepal’s prison population are scarce, according to a survey PDS-Nepal conducted in 2017, “lower-caste” people (Dalit, Janajati, and Madhesi) represent a larger portion of the prison population than “upper-caste” groups (Brahmin, Chhettri).

Around the world, discrimination, lack of access to education, and increased rates of poverty impact a person’s ability to access justice. For the Dalit community in Nepal, these factors increase the rates at which Dalits are arrested, while limiting knowledge about their legal rights, and reducing access to defense lawyers. Additionally, bail is commonly required in Nepal for people accused of even low-level crimes, disproportionately impacting Dalit defendants who lack the resources to pay. Thus, the poorest and most marginalized people suffer even more, languishing in jail awaiting trial. The resulting job loss and stigma exacerbate the cycle of poverty .

Yet, the justice system doesn’t have to be this way: quality legal aid can help level the playing field. More than 70% of our PDS-Nepal clients belong to marginalized communities and without legal aid, would not have access to a lawyer. When people accused of crimes have access to effective lawyers , they are less likely to be tortured, less likely to be subject to discrimination, and more likely to be released ahead of trial.

The fight to end caste discrimination in Nepal is far from over. We must continue to support Nepal’s marginalized communities and the many organizations that are fighting for their rights. In the criminal justice system, we must ensure that everyone has access to a quality lawyer who understands the particular challenges faced by underserved communities and will advocate for dignity, fairness, and justice for all.

Recent Posts

The ILF's Statement to the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, 33rd Session

Collaborating to Expand Access to Legal Aid in the Global South

Georgia Launches Efforts to Measure Quality of Legal Aid Services

Nepal’s caste struggle

On 15 June, 24-year-old Rupa Sunar, a Dalit media person went to the house of Saraswti Pradhan in Kathmandu’s Babar Mahal with two friends. They discussed and agreed on the terms and conditions of a rental agreement. House-owner Pradhan apprised Sunar of the rules: that she should not make noise, should to be out late, and cooperate with her.

At the end of the meeting, Pradhan asked Sunar about her caste. Upon learning of her ‘lower’ caste status , she said that she would convey her decision after family consultation. Pradhan called Sunar’s friend an hour later, and told that she could not rent the room to a ‘lower’ caste person.

Sunar phoned Pradhan to confirm. She recorded the conversation: “I cannot rent you the room. Our elderly mother lives with us. She cannot share the house with a lower caste. But please let me know if other friends need a room.’

According to the 2011 Census, Dalits make up of 14% of Nepal's population. Many ‘higher’ caste people still do not consume food and beverages touched by a Dalit persons. To maintain ritual purity, the ‘higher’ caste families do not let Dalits enter their houses. In 2001, one study identified over 205 forms of such discriminatory practices.

The 1990 Constitution outlawed caste-based discrimination and

untouchability. But historically, most laws remain on paper only. Violations mostly go unpunished.

In 2011, the Constituent Assembly enacted the Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability (Offense and Punishment) Act. The Act prohibits caste-based discrimination ‘in any public or private place.’

For example, the act forbids preventing someone from entering a house or evicting them on the ground of caste or race. The act made caste-based discrimination a crime against the state. Hence, in the caste-based discrimination cases, the state becomes a party, which requires it to file the cases in court, investigate and defend them.

In January 2021, Nepal was re-elected for a second term on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), an international body responsible for the promotion and protection of human rights around the world.

But in Nepal last week, a sitting minister interfered with and obstructed a police investigation of a caste-based discrimination case. International human rights laws define caste-based discrimination as human rights violations.

On 17 June, two days after being refused the flat, Sunar lodged a complaint against Pradhan at the Metropolitan Police Office, Singha Darbar, accusing her of caste-based discrimination .

The police initially denied registering the complaint. Despite laws criminalising it, the Police, government attorneys, and judges often do not recognise caste-based discrimination cases as an offence, and in fact dissuade people from filing such complaints.

Only after the case attracted public attention did the police finally register Sunar’s complaint, and initiate an investigation. On 20 June, the Police arrested Pradhan, and put her in custody.

The case soon took on an ethnic colour, with some making it out to be a Dalit vs Newa issue. Some Newa organisations released statements asking the police to punish Sunar for disrupting social harmony. Former senior government officer Bhim Upadhyaya accused Sunar of fomenting societal tension. Instead of standing up against caste discrimination, the Mayor of Madhyapur Thimi on Monday called for Sunar to be prosecuted.

Sudha Tripathi, the former Tribhuvan University registrar, described Sunar as a Dalit ‘gangster’. Thousands of their social media followers shared these statements.

All Sunar wanted was a room to live in, just like anyone else in Nepal. Why was that such a problem?

As we know, the story did not end there. On 23 June, the Minister of Education, Science, and Technology Krishna Gopal Shrestha drove to the station in his official car, pressured the Police to release Pradhan and even posed for a photoshoot with her in front of media.

Nepal’s national flag fluttered from his ministerial vehicle as he drove Pradhan home. Not only did Minister Shrestha have no authority to handle this case, he misused state authority and state resources.

As the minister belonged to the same ethnic group as Pradhan, he abandoned his state responsibility and took a communal stance. Minister Shrestha’s triumphant pose with Pradhan ignited a firestorm of hatred against Dalits on social media, prompting users to vow never to rent rooms to Dalits.

There have also been threats of violence. Dalit activists have received death threats for speaking out. Dalit leaders and rights activists have called on the government to act against Minister Shrestha, and create a conducive environment for fair trial. Dalits and non-Dalits have even demonstrated in the streets to protest the state inaction and minister’s unlawful action.

However, Prime Minister K P Oli has been silent on the issue. On 24 June, he even assigned Minister Shrestha four additional portfolios. But his government has not done anything to assure the victims and the Dalit community a fair trial and protection of their lives and human rights.

The failure of state to assure the Dalit community of justice has made them feel unprotected and vulnerable. They fear that in the future no law enforcement agency will register and try cases of caste-based discrimination. They also fear the possibility of retaliation by members of ‘higher’ castes.

Nepal is a party to Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the

International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The ICERD specifically prohibits any form of state engagement in practicing, sponsoring, defending, or supporting any forms of racial or descent-based discrimination.

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is supposed to protect Nepali citizens from violations. However, after the government appointed the new NHRC members bypassing parliamentary hearing on 3 February, UN human rights experts have expressed concern about its independence. This is proven by its complacency about Minister Shrestha’s involvement in the Rupa Sunar case.

The Dalit community in Nepal is looking to international human rights groups, including the United Nations, to question the government’s accountability. Maintaining silence and inaction when human rights are violated will only escalate tension. Inaction will not create an environment for world-wide respect to human rights necessary for peace and justice.

Kunjani Pariyar Pyasi is a human rights lawyer. Binita Nepali is a graduate of International Relations and Diplomacy from TU. They are also the participants of Dalit Reader’s Writing Workshop.

- caste discrimination

‘Art Lover’ accused of sexual abuse

Ufo over pokhara, what nepal’s vip prisoners do in jail, here comes the nepal premier league.

- Developing Stories

- Creative Series

- Press releases

- Signup for our newsletter Our Editors' Best Picks Send I hereby confirm that I wish to receive FairPlanet's newsletter. I have read, understood and confirm FairPlanet's Privacy Policy . * .

- Discrimination

From Prejudice to Progress: Combating caste and LGBTQ+ discrimination in Nepal

Gauri Nepali had always known that she was different from other children in Kabri, a small village in Nepal. She belonged to a lower caste, and as a result, was constantly reminded of her place in society.

One day, when she was just a child, Nepali went to her friend's house. The kitchen had a tap under which utensils were stacked on top of one another. When she ran over towards the tap, her friend's family members forbade her from accessing that part of the kitchen. They claimed that if she touched the water it would become polluted. Nepali was confused and hurt, and that experience had scarred her ever since.

“I stopped making friends and going out. I would play at home alone. My parents became my friends,” the 33-year-old told FairPlanet. She said that the lack of communication and interaction with her peers caused her to become introverted.

As she grew up, Nepali’s social and networking opportunities remained limited - both because she was Dalit and LGBTQ+. After completing her Master's in Nepali literature, Nepali had found the courage to come out to her best friend. Unfortunately, her friend has not spoken to her for over three years since that time.

“My psychology and mental health were impacted during those years, because I felt that even a close friend of mine thinks in the way of society,” she said.

Caste discrimination and LGBTQ+ marginalisation are both prevalent in Nepal and often intersect, which results in unique challenges for those who belong to both communities. And while discrimination based on one's caste or sexual orientation is considered a violation of human rights according to the country’s constitution, queer people and Dalits continue to face difficulties in accessing education, employment opportunities and social integration.

Activists and members of Nepal’s LGBTQ+ community remain adamant that solutions exist to create a more inclusive society for all. However, they have yet to see them implemented in Nepalese society.

Double Discrimination

Caste discrimination is rooted in Nepal’s history and culture, and the hierarchical caste system continues to affect the lives of millions, particularly those from lower castes, in areas such as education, employment, healthcare and justice.

In contrast, Nepal has made notable progress when it comes to LGBTQ+ rights, with a 2007 Supreme Court ruling recognising them as fundamental human rights. However, despite the passing of laws protecting LGBTQ+ rights and the country's reputation as being queer-friendly, deploy-held negative social attitudes and prejudice against queer people continue to inspire stigma and discrimination towards the community.

This ongoing marginalisation is experienced separately by members of both communities, except for in cases where intersectionality is at play: some members of the LGBTQ+ community also belong to lower castes, and thus experience “double discrimination.”

“Society has excluded Dalits or lower-caste people anyways. But when you reveal that you are transgender or part of the LGBTQI+ community, the chances of double discrimination are higher,” Pinky Gurung, President of the Blue Diamond Society of Nepal, told FairPlanet. “Society discriminates when you are a Dalit. But when you are part of the LGBTQI+ community, society and family both discriminate.”

rights violated

Nepal has enacted several policies to eradicate both caste discrimination and LGBTQ+ rights infringements.

The Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability Act of 2011 criminalises caste-based discrimination and untouchability practices, and prescribes penalties for related offences. The Muluki Ain, originally drafted six decades ago, was amended in 1991 to include a punishment for discriminatory acts. The 2015 Constitution of Nepal prohibits discrimination based on caste, gender and sexual orientation, and recognises queer rights as fundamental rights, including the right to obtain a citizenship certificate that corresponds to one’s gender identity.

But despite these broad legal protections, many LGBTQ+ Nepalis continuously face challenges in accessing education . Many transgender youths, for instance, are being compelled to drop out due to increased bullying incidents, which subsequently leads to decreased employment opportunities and participation in public life, according to a report by Blue Diamond Society (BDS) and the Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights - Global Initiative for Sexuality and Human Rights.

“While applying for a job, [candidates are expected to have a university degree] - but that is a disadvantage for us, as Dalit and queer do not have a strong education. Companies also look for people strong in English or Nepali language. But the access to the language has not been given to the Dalit community,” said Nepali from Kabri.

A 2015 report by the Dalit Civil Society Organizations' Coalition for UPR, Nepal and International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) found that the literacy rate among Dalits stood at 52.4 percent, which was lower than the national average of 65.9 percent. A different report from 2009 by the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies had found that only 15 percent of the Dalit population has educational credentials, which is nearly half of the national average.

The same report also revealed that nearly 50 percent of enrolled children fail to complete primary education due to caste-based discrimination by non-Dalit students and teachers, parents’ insistence that children prioritise household chores, schools being located far from Dalit communities, as well as general frustration and depression.

“On top of that, if you add the LGBTQI+ community, very few transgender and queer people have been allowed to study. Most of the people in my network have left studying after the 12th grade,” Nepali said.

Furthermore, the significant obstacles in accessing education among Dalits lead to a lack of exposure to LGBTQ+ issues, which undermines their understanding and acceptance of the community. A study conducted in Nepal by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Blue Diamond Society found that individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to have positive attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people and their rights.

The same report also revealed that queer Nepalis face discrimination in public healthcare facilities, with doctors denying treatments and privately-owned transportation businesses denying them access to rides.

They have also been the target of attacks and harassment, which at times result in murder .

Mental health affected

This engenders a prevalent sense of inferiority among queer Nepalis, which often prevents them from coming out and embracing their identity, according to Rabina G. Rasaily, Executive Director at the Nepal-based Feminist Dalit Organization.

“We don’t have that kind of environment at the household, family or community level. I think that is a very basic problem in terms of identification,” she added.

Nepali seconds Rasaily. Based on her own experiences and interactions with other community members, she has observed that individuals who carry a dual identity are generally not outspoken.

“We have come from a marginalised background. We don’t have an environment where we can put our points strongly about how we feel or what we want,” she said.

Potential solutions

Nepali activists argue that the first step in addressing the discrimination of Dalits and LGBTQ+ people in the country is raising public awareness. “In Nepal’s society, people need to show equal behaviour irrespective of caste, physical status or geography. They should treat everyone as an equal and human. That’s the thought people should have,” said Nepali.

They point out, however, that this would be no easy task, particularly in cases of caste and LGBTQ+ intersectionality, which would require the unlearning of deep-seated prejudices.

“In our Hindu society, the caste system is still prevalent where the Dalits and other marginalised castes have been facing discrimination and exclusion from the society every day,” said Rasaily.

They further point to the importance of implementing existing policies designed to protect these minorities and expanding their scope.

“It has been over 70 years of the Dalit movement in Nepal, but there are a lot of drawbacks in the movement despite that. All the policies made to target the Dalit community have taken into account only the binary genders. That’s also true for every other policy,” said Nepali, who believes that policies protecting sexual and gender minorities should be considered alongside laws protecting other types of minorities, including lower caste members.

“The ultimate beneficiaries are our [communities], and for that we need legal recognition of such communities in terms of accessing the basic rights like health care, education and employment opportunities so that they can also live a dignified life,” said Rasaily, who believes that a multi-sectoral, integrated approach is key in addressing discriminatory sentiments and practices.

Image by Kandukuru Nagarjun .

Related Sustainable Development Goals

Related articles of human rights.

- Editors’ Picks

- Editors’ Voices

- The Beam Magazine

- FairPlanet Media Advertising Kit

- FairPlanet Media Services

- FairPlanet Social Enterprise

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Our Coverage

- Editors´ picks

- Authors Network

- Editorial Policy

- Equality and Diversity

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- © 2024 FairPlanet

- All rights reserved

By copying the embed code below, you agree to adhere to our republishing guidelines .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Social discrimination on account of inequality has been in practice between upper caste and lower scheduled caste people. Brahmins are subjected as upper level castes that are known to be scholars, educators, traditionally priest and so on. Top caste enjoys more rights and those at bottom performing more duties got no rights.

3 Caste-based Discrimination in Nepal Krishna B. Bhattachan, Tej B. Sunar and Yasso Kanti Bhattachan(Gauchan) many terms to refer to Dalits. Some terms, such as paninachalne (water polluting), acchoot (untouchables), doom, pariganit, and tallo jat (low caste) are derogatory, while other terms, such as uppechhit (ignored), utpidit (oppressed), sosit (exploited), pacchadi pareka (lagging behind ...

Caste-Based Discrimination In Contemporary Nepal: A p ro b l e ma t i sa t i o n o f N e p a l ' s n a t i o n a l p o l i ci e s t h a t a d d re ss d i scri mi n a t i o n b a se d o n ca st e . Aastha Kc Human Rights Studies Bachelor Thesis 15 Credits Spring 2020 Supervisor: Dimosthenis Chatzoglakis

This paper analyzes caste-based discrimination and educational inequalities among Dalits using the deconstructive lens. The article reflects on Nepal's 1990 and 2015 constitutional provisions on ...

In Nepal, more than 400,000 individuals out of the country's 30 million population belong to a community known as the untouchables. Members of this community, like Prem Pariyar, identify themselves as Dalits, which translates to 'the oppressed.' Raised within this caste system, Prem encountered discrimination at every stage of his life.

discrimination, including untouchability, is still ubiquitously practiced in Nepal in many different ways. Caste based untouchability is nothing but one of the worst form of human rights violations and crime against humanity. Dalit movement against caste based discrimination began in early 1950s with focus on entry in Hindu temples and later co ...

The recent murder of a young Dalit man, Nawaraj BK, and his five friends was a tragic reminder for the world that caste discrimination is still very much alive in Nepal. The murders sparked protests around the country calling for justice, and the issue goes far beyond this act of violence. Discrimination against people considered lower-caste has all too often meant that they are ignored as ...

Hence, in the caste-based discrimination cases, the state becomes a party, which requires it to file the cases in court, investigate and defend them. In January 2021, Nepal was re-elected for a second term on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), an international body responsible for the promotion and protection of human rights ...

Caste discrimination is rooted in Nepal's history and culture, and the hierarchical caste system continues to affect the lives of millions, particularly those from lower castes, in areas such as education, employment, healthcare and justice. ... But the access to the language has not been given to the Dalit community," said Nepali from ...

The present publication contains the report on Nepal, prepared in collaboration with the Department of Anthropology/Sociology of Tribhuvan University under the coordination of Dr. Tulsi Ram Panday and his research team, Mr. Dambar Chemjong, Mr. Surendra Mishra, Mr. Sanjeev Pokhrel and Mr. Nabin Rawal.