- 1-888-SNU-GRAD

- Daytime Classes

The 8 Most Asked Questions About Dissertations

A Ph.D. represents the highest level of education in most fields. People who earn this degree earn the honorific of “doctor” and are considered experts in their field. A doctoral degree is often a prerequisite for teaching at the highest levels in academia or ascending career ladders in education, the government and the nonprofit space.

In 2020 , doctoral degree holders had median weekly earnings of $1,885 and an unemployment rate of 2.5%—lower than any other group. And yet, the dissertation is often a major barrier to completing a doctorate and realizing its many financial and personal benefits.

So what is a dissertation, and what role does it play in your educational trajectory? At SNU, we value exceptional dissertations and integrate the writing process into your coursework. Here are the most common questions we hear about writing dissertations and earning your doctorate.

1. What is a dissertation?

A dissertation is a published piece of academic research. Through your dissertation research , you become an expert in a specific academic niche. After writing your dissertation, you then defend it to a committee of experts in the field. A dissertation is integral to the process of earning a doctoral degree, contributing innovative ideas to your chosen field. Until you have written, published and defended a dissertation, you can’t graduate from a doctoral-level program.

2. Why are dissertations so important?

Dissertations are the crucial piece of research in most doctoral-level programs. The process of writing, researching and amending the dissertation serves several important goals:

- It contributes novel research to the field, supporting innovation, growth and ongoing scholarship.

- It requires students to write a substantive piece of academic research across many semesters, sharpening research skills and expertise.

- It demands that s tudents defend their research, ensuring strong communication and critical thinking skills.

- It requires deep, comprehensive research—including a literature review—improving reading comprehension and writing skills.

- It is a challenging project that serves as a test of the skills you might use as an academic professional in your chosen field.

- It helps establish new members of an academic discipline as contributors to the field.

- It fosters academic connections as you interview sources and defend your work.

3. Why do so many students struggle with the dissertation?

The dissertation process is difficult. However, this difficulty establishes the credibility of doctoral degrees, proving that the student can commit to long-term, intensive research and become a true subject-matter expert.

However, for many adult learners, the dissertation proves especially challenging thanks to work-life balance difficulties, financial constraints and lack of family or institutional support. At SNU, we know that a dissertation is critical to your growth as an academic. But we also know that institutional support can make a big difference in your ability to finish this impressive work. That’s why we integrate dissertation writing into our curriculum, rather than leaving you to do it all on your own time.

One study suggests that more than half of students never complete their dissertation. Other research indicates that academic reforms that help students with their work reduce dropout rates, ensuring more students complete their dissertation and earn the coveted title of doctor.

4. How long is a dissertation?

Most dissertations are 100 pages or longer — roughly the length of a book. The specific length of your dissertation depends on the type of research, how much research exists in the field and similar factors. The goal of dissertation writing is not to attain a specific length, but to be comprehensive and thoughtful. It anticipates and answers potential objections, gives appropriate credit to the source materials and reviews prior work in the field.

Your dissertation review committee is more interested in a comprehensive dissertation that displays your critical thinking and research skills than they are in a dissertation of a specific length. Excessive wordiness without value wastes a reader’s time.

The right length for a dissertation depends on several factors:

- How much research already exists in the field?

- What field are you publishing in?

- What type of research are you doing?

- Is your research controversial?

- How much space do you need to explain your research and address objections?

Put simply: A dissertation should be long enough to comprehensively cover the subject, but no longer.

5. How do you write a dissertation?

In general, the dissertation process follows this schedule:

- Research the field and identify potential topics.

- Meet with an advisor to choose and improve a topic.

- Perform a literature review.

- Conduct new research.

- Write the dissertation.

- Edit the dissertation.

- Defend the dissertation.

Each step involves weeks to months of work and many phases of revision, reevaluation and research. At SNU, we incorporate many phases of the writing and research process into your coursework. This ensures you are on track to graduate and addresses dissertation writing challenges before they snowball into a serious problem.

6. When should you start writing a dissertation?

The dissertation writing process should begin almost as soon as you enroll in school. That doesn’t necessarily mean you need to have content written on your first day of class. Instead, you will need to engage in substantive pre-writing that includes:

- Familiarizing yourself with relevant research in the field.

- Developing an opinion on recent research.

- Designing your research to address a clear and narrowly defined topic.

As you hone in on your topic, you can begin the writing and research portion of the project. In most cases, this starts within a semester or two of enrollment. A dissertation is not something you can leave until the last semester or shortly before graduation. SNU ensures this doesn’t happen by integrating the writing process into your coursework. You will start working on your dissertation early, preventing you from becoming overwhelmed.

7. How do you cite a dissertation?

A dissertation is a published scholarly work. Each style manual has specific instructions for citing a dissertation, so be sure to consult the style manual you’re using.

You can cite other dissertations in your dissertation. In many cases, dissertations can provide useful starting points for your research. The literature reviews they contain may also help with your literature review.

8. How do you choose a school for your dissertation?

Choosing the right school for your dissertation can mean the difference between finishing this scholarly work and languishing at the dreaded “ all-but-dissertation” (ABD) stage . SNU specializes in supporting adult learners by encouraging intensive research and protecting your work-life balance.

At SNU, your dissertation is a part of your coursework . You will get support from start to finish, including a dissertation advisor who is an expert in your chosen field. We are here for you, and we want to see you succeed.

Want to learn more about SNU's programs?

Request more information.

Have questions about SNU, our program, or how we can help you succeed. Fill out the form and an enrollment counselor will reach out to you soon!

Subscribe to the SNU blog for inspirational articles and tips to support you on your journey back to school.

Recent blog articles.

Veteran Students

Campus Spotlight: Southern Nazarene University’s VETS Center

Adult Education

The Value of Military Experience in the College Classroom

Leveraging Military Experience in Criminal Justice

From Boot Camp to Bit Camp: A Guide to Cybersecurity for Vets

Have questions about SNU or need help determining which program is the right fit? Fill out the form and an enrollment counselor will follow-up to answer your questions!

Text With an Enrollment Counselor

Have questions, but want a faster response? Fill out the form and one of our enrollment counselors will follow-up via text shortly!

- Accessibility Tools

- Undergraduate Degrees

- Postgraduate Degrees

- Cyber Security

- Computing & Tech

- Project Management

- All courses

- Your country

- Pre-arrival information

- Finance & funding

- Entry requirements

- Accommodation

Studying in London

- Student support

- Why Northumbria London

- Meet our students

- Meet our faculty

- Our campus & virtual tour

- News & stories

- Working with businesses

- Your Prospectus

- Enquire now

International Students

Working professionals.

- How to Apply

- Enquire Now

Subject Areas

New students, study levels, upcoming start-dates, study options, your country, part-time masters.

- What to Expect with Weekend Study

- Financing Options

Why Northumbria

- Make a Payment

- All Courses

- Dates and Fees

- Scholarships

- Student Budget Calculator

- Pre-Arrival Information

- Enrolment Information

- Pre-Masters

- Pre-sessional English and Study Skills

- Study in January

- Study in May

- Study in September

- Blog: Full-Time or Part-Time?

- Advanced Practice

- Internships

- European Union

- All Countries

- MSc Business with International Management

- MSc Cyber Security

- MSc Cyber Security Technology

- MSc Programme and Project Management

- Northumbria University London Student Guide

- Meet Our Students

- Meet Our Faculty

- I Am Northumbria

- Student Support

- Cost of Living

- Professional Pathways

- Our London Campus Partner

- Consultancy Clinic

- Virtual Tour

- How to find us

- Virtual 16th International Conference on Global Security, Safety & Sustainability, ICGS3-24

15 Essential Dissertation Questions Answered

This National Dissertation Day, we asked our dissertation advisers to answer some of the most common questions they get asked by students. These range from what you need to know before you start, tips for when you’re writing, and things to check when you’ve finished.

1. Before you start writing

Q: What is a dissertation?

A: A research project with a word count of 12,000+ at Master’s level.

Q: What is the difference between a postgraduate and an undergraduate dissertation?

A: The length for Undergraduate is less than 12,000 words and for Postgraduate it is more than 15,000 words. Level 7 requires a higher level of critical debate, better synthesis of the arguments, and more independence in research. It also requires originality and an attempt to touch, challenge, or expand the body of existing knowledge.

Q: How much time should be spent writing a dissertation?

A: An Undergraduate dissertation is worth is 40 credits (from 360 in total) and should take 300-400 hours. A Postgraduate dissertation is worth 60 credits (from 180 in total) and should take 400-600 hours.

Q: What is the best way to pick a topic and where should the focus be when writing?

A: As per your pathways of study and incorporating your areas of interest, based on previous research papers and contemporary or futuristic issues.

Q: What kind of research do students need to complete before starting?

A: Both Undergraduate and Postgraduate students study a module on research methodology and develop a research proposal, based on previous research.

2. Whilst you write your dissertation

Q: Can dissertations include other media i.e. imagery, videos, graphs, external links to examples?

In most programmes this is not possible, however specific programmes such as MA design, media studies, or architecture may allow various media to be included.

Q: How much support is offered by advisers?

A: Students are offered 4 hours of one-to-one supervision spread over 12-14 weeks of a term.

Q: Are students able to submit multiple drafts?

Yes, this is allowed.

Q: What is the policy on dissertation deadline extensions?

A: A student can be granted late authorisation (two extra weeks) or personal extenuating circumstances, but there needs to be evidence to support the requests.

3. What advisers see after the dissertation submission

Q: What are some of the most common mistakes advisers see with dissertations?

A: The following:

- Non-focused research objectives and a lack of SMART research topics

- Not enough depth and critical debate in the literature review

- A lack of justification of research methods and not using a reliable questionnaire

- A failure to use required methods of qualitative or quantitative research

- Not discussing their results

Q: What makes a truly great dissertation?

- A well-structured piece of work with a clear introduction, literature review, research methods, findings, discussions, and conclusions

- A dissertation that follows TAASE (Theory, Applications, Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation)

- Work that meets the module’s learning objectives

Q: What does excellent collaboration between a student and an adviser look like?

A: Regular planned meetings, mutual respect, and a partnership where both of the parties are motivated and inspired for the research.

Q: What’s one key piece of advice you can give to prospective Master’s students on dissertation writing?

A: Critically read and benchmark previous peer-reviewed research journals in your area of research. Regularly attend supervision meetings and work continuously and not only towards the end of the term. Be honest and ethical in your data collection.

If you need more information about dissertation writing or pursuing a degree, please contact us using the details below:

- To find out more about our courses: https://london.northumbria.ac.uk/courses/

- For support with study skills please email your Academic Community of Excellence (ACE) Team .

Related posts

Quick contact

- I'm interested in a Pre-Sessional English Course.

In future QA Higher Education would like to contact you with relevant information on our courses, facilities and events and those of our University Partners. Please confirm you are happy to receive this information by indicating how you would like us to communicate with you below:

Please note, this will overwrite any previous communication preferences you may have already specified to us on our website or websites relating to our University Partners. You can change your communication preferences at any time. QA Higher Education will process your personal data as set out in our privacy notice

Hidden Fields

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this website, you agree to our Cookie Notice & Privacy Notice .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started

Published on 26 March 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 5 May 2022.

A dissertation is a large research project undertaken at the end of a degree. It involves in-depth consideration of a problem or question chosen by the student. It is usually the largest (and final) piece of written work produced during a degree.

The length and structure of a dissertation vary widely depending on the level and field of study. However, there are some key questions that can help you understand the requirements and get started on your dissertation project.

Make your writing flawless in 1 upload

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

When and why do you have to write a dissertation, who will supervise your dissertation, what type of research will you do, how should your dissertation be structured, what formatting and referencing rules do you have to follow, frequently asked questions about dissertations.

A dissertation, sometimes called a thesis, comes at the end of an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. It is a larger project than the other essays you’ve written, requiring a higher word count and a greater depth of research.

You’ll generally work on your dissertation during the final year of your degree, over a longer period than you would take for a standard essay . For example, the dissertation might be your main focus for the last six months of your degree.

Why is the dissertation important?

The dissertation is a test of your capacity for independent research. You are given a lot of autonomy in writing your dissertation: you come up with your own ideas, conduct your own research, and write and structure the text by yourself.

This means that it is an important preparation for your future, whether you continue in academia or not: it teaches you to manage your own time, generate original ideas, and work independently.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

During the planning and writing of your dissertation, you’ll work with a supervisor from your department. The supervisor’s job is to give you feedback and advice throughout the process.

The dissertation supervisor is often assigned by the department, but you might be allowed to indicate preferences or approach potential supervisors. If so, try to pick someone who is familiar with your chosen topic, whom you get along with on a personal level, and whose feedback you’ve found useful in the past.

How will your supervisor help you?

Your supervisor is there to guide you through the dissertation project, but you’re still working independently. They can give feedback on your ideas, but not come up with ideas for you.

You may need to take the initiative to request an initial meeting with your supervisor. Then you can plan out your future meetings and set reasonable deadlines for things like completion of data collection, a structure outline, a first chapter, a first draft, and so on.

Make sure to prepare in advance for your meetings. Formulate your ideas as fully as you can, and determine where exactly you’re having difficulties so you can ask your supervisor for specific advice.

Your approach to your dissertation will vary depending on your field of study. The first thing to consider is whether you will do empirical research , which involves collecting original data, or non-empirical research , which involves analysing sources.

Empirical dissertations (sciences)

An empirical dissertation focuses on collecting and analysing original data. You’ll usually write this type of dissertation if you are studying a subject in the sciences or social sciences.

- What are airline workers’ attitudes towards the challenges posed for their industry by climate change?

- How effective is cognitive behavioural therapy in treating depression in young adults?

- What are the short-term health effects of switching from smoking cigarettes to e-cigarettes?

There are many different empirical research methods you can use to answer these questions – for example, experiments , observations, surveys , and interviews.

When doing empirical research, you need to consider things like the variables you will investigate, the reliability and validity of your measurements, and your sampling method . The aim is to produce robust, reproducible scientific knowledge.

Non-empirical dissertations (arts and humanities)

A non-empirical dissertation works with existing research or other texts, presenting original analysis, critique and argumentation, but no original data. This approach is typical of arts and humanities subjects.

- What attitudes did commentators in the British press take towards the French Revolution in 1789–1792?

- How do the themes of gender and inheritance intersect in Shakespeare’s Macbeth ?

- How did Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia influence nineteenth century utopian socialist thought?

The first steps in this type of dissertation are to decide on your topic and begin collecting your primary and secondary sources .

Primary sources are the direct objects of your research. They give you first-hand evidence about your subject. Examples of primary sources include novels, artworks and historical documents.

Secondary sources provide information that informs your analysis. They describe, interpret, or evaluate information from primary sources. For example, you might consider previous analyses of the novel or author you are working on, or theoretical texts that you plan to apply to your primary sources.

Dissertations are divided into chapters and sections. Empirical dissertations usually follow a standard structure, while non-empirical dissertations are more flexible.

Structure of an empirical dissertation

Empirical dissertations generally include these chapters:

- Introduction : An explanation of your topic and the research question(s) you want to answer.

- Literature review : A survey and evaluation of previous research on your topic.

- Methodology : An explanation of how you collected and analysed your data.

- Results : A brief description of what you found.

- Discussion : Interpretation of what these results reveal.

- Conclusion : Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your findings contribute to knowledge in your field.

Sometimes the order or naming of chapters might be slightly different, but all of the above information must be included in order to produce thorough, valid scientific research.

Other dissertation structures

If your dissertation doesn’t involve data collection, your structure is more flexible. You can think of it like an extended essay – the text should be logically organised in a way that serves your argument:

- Introduction: An explanation of your topic and the question(s) you want to answer.

- Main body: The development of your analysis, usually divided into 2–4 chapters.

- Conclusion: Answers to your research question(s) and summary of what your analysis contributes to knowledge in your field.

The chapters of the main body can be organised around different themes, time periods, or texts. Below you can see some example structures for dissertations in different subjects.

- Political philosophy

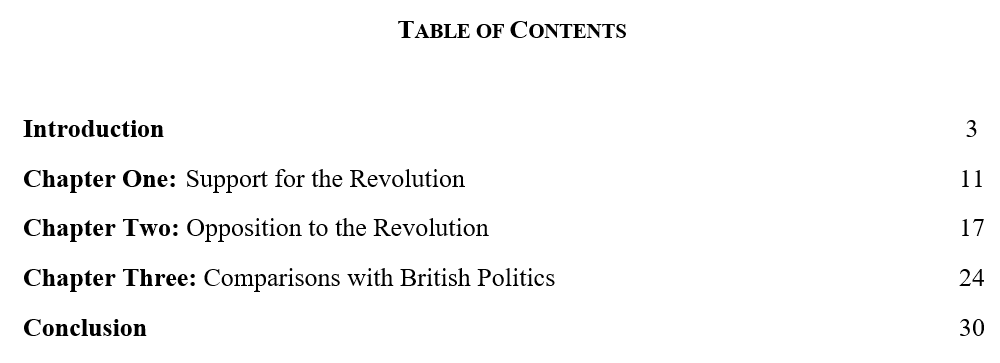

This example, on the topic of the British press’s coverage of the French Revolution, shows how you might structure each chapter around a specific theme.

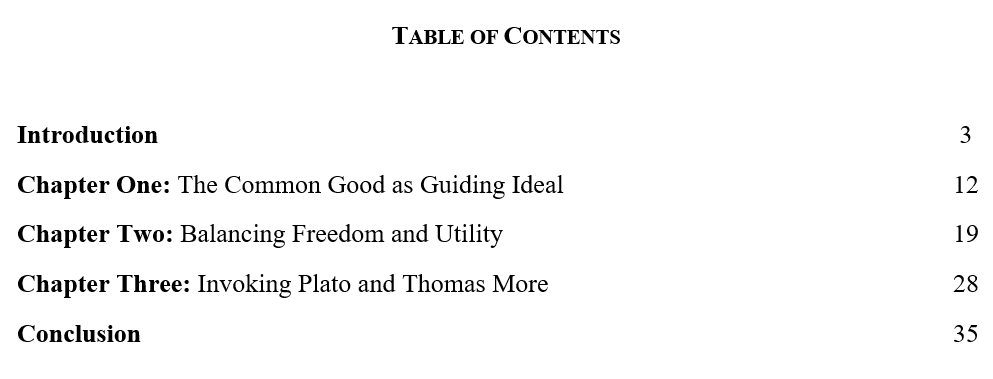

This example, on the topic of Plato’s and More’s influences on utopian socialist thought, shows a different approach to dividing the chapters by theme.

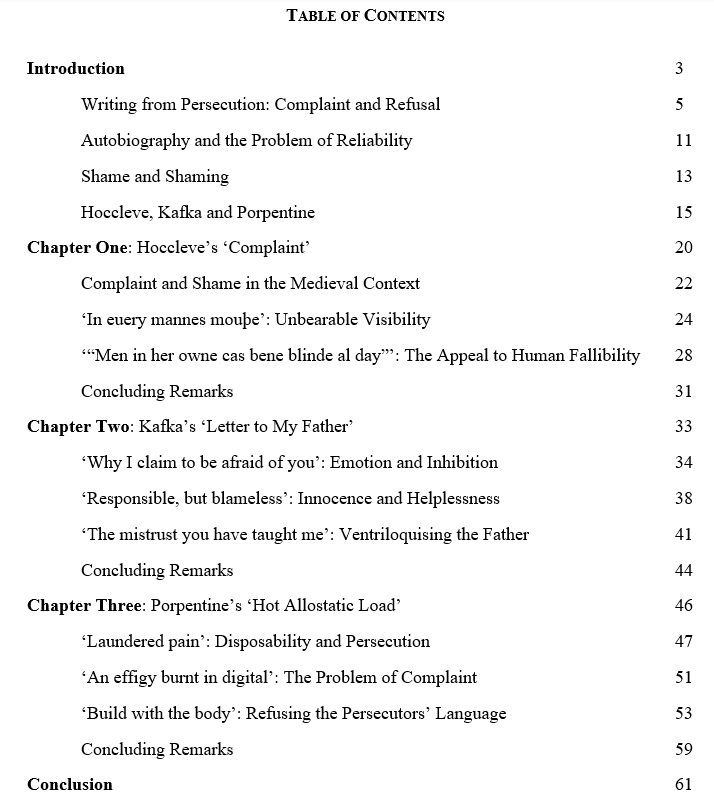

This example, a master’s dissertation on the topic of how writers respond to persecution, shows how you can also use section headings within each chapter. Each of the three chapters deals with a specific text, while the sections are organised thematically.

Like other academic texts, it’s important that your dissertation follows the formatting guidelines set out by your university. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

Formatting guidelines concern things like:

- line spacing

- page numbers

- punctuation

- title pages

- presentation of tables and figures

If you’re unsure about the formatting requirements, check with your supervisor or department. You can lose marks unnecessarily over mistakes, so it’s worth taking the time to get all these elements right.

How will you reference your sources?

Referencing means properly listing the sources you cite and refer to in your dissertation, so that the reader can find them. This avoids plagiarism by acknowledging where you’ve used the work of others.

Keep track of everything you read as you prepare your dissertation. The key information to note down for a reference is:

- The publication date

- Page numbers for the parts you refer to (especially when using direct quotes)

Different referencing styles each have their own specific rules for how to reference. The most commonly used styles in UK universities are listed below.

You can use the free APA Reference Generator to automatically create and store your references.

APA Reference Generator

The words ‘ dissertation ’ and ‘thesis’ both refer to a large written research project undertaken to complete a degree, but they are used differently depending on the country:

- In the UK, you write a dissertation at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a thesis to complete a PhD.

- In the US, it’s the other way around: you may write a thesis at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a dissertation to complete a PhD.

The main difference is in terms of scale – a dissertation is usually much longer than the other essays you complete during your degree.

Another key difference is that you are given much more independence when working on a dissertation. You choose your own dissertation topic , and you have to conduct the research and write the dissertation yourself (with some assistance from your supervisor).

Dissertation word counts vary widely across different fields, institutions, and levels of education:

- An undergraduate dissertation is typically 8,000–15,000 words

- A master’s dissertation is typically 12,000–50,000 words

- A PhD thesis is typically book-length: 70,000–100,000 words

However, none of these are strict guidelines – your word count may be lower or higher than the numbers stated here. Always check the guidelines provided by your university to determine how long your own dissertation should be.

At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, the dissertation is usually the main focus of your final year. You might work on it (alongside other classes) for the entirety of the final year, or for the last six months. This includes formulating an idea, doing the research, and writing up.

A PhD thesis takes a longer time, as the thesis is the main focus of the degree. A PhD thesis might be being formulated and worked on for the whole four years of the degree program. The writing process alone can take around 18 months.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, May 05). What Is a Dissertation? | 5 Essential Questions to Get Started. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 December 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/what-is-a-dissertation/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples.

Writing the Dissertation - Guides for Success: Research Question

- Writing the Dissertation Homepage

- Overview and Planning

- Research Question

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Results and Discussion

- Picking a Topic

- Questions and Hypotheses

- Room for Refinement

- Action Words

- Preparing to Research

Overview of developing research questions

Effective writing should have a clear purpose, and purpose shines through the best when an essay or dissertation responds to an explicit research question(s). Sometimes, you will need to define or refine a research question based on an essay title provided by an instructor. In the case of dissertations and theses, you will start from scratch, developing one or more research question(s) to anchor and guide a major piece of work.

A research question is powerful: it shapes the focus and breadth of your reading, suggests the data you will need to access or produce, underpins choices related to method/methodology, and more. Therefore, it's crucial to build experience both in inventing and amending research questions.

Guide contents

The tabs of this guide will support you in developing research questions and/or hypotheses to get your writing project started. The sections are organised as follows:

- Picking a Topic - Tips on finding the broad starting place for your essay or writing project.

- Questions and Hypotheses - Learn how to develop your idea into a workable hypothesis or research question.

- Room for Refinement - Explore ways to fine-tune your question to allow maximum depth and criticality.

- Action Words - Help deciding on the right verbs to frame what you will do in your writing.

- Preparing to Research - With your question decided, here's a concise outline to begin the research process.

Getting started: the topic

The first things you will need to do when starting your research are to think of a subject or topic for your writing project and design either a hypothesis (a statement for investigation) or question that you will address. Let's start with picking the subject.

Inspiration

When embarking on a thesis or dissertation , you can find the inspiration for your research topic from anywhere: for example, the media, current affairs, art, literature, technology, or your course notes and general reading interests. Above all, it is important that you are interested in and enthusiastic about your topic. You will be a more successful researcher if you care about your project.

If you are starting an essay rather than a final project, odds are you will be assigned a general subject. However, within the broad essay title/instructions, there may be scope to tailor the focus.

– Our Understanding the Assignment guide goes into more depth about unpicking and responding to assigned essay titles.

Your supervisor's role

You needn't discuss your approach to every essay with the lecturer ahead of time. However, if working on a major project , make sure you discuss your topic with your supervisor. This includes chatting with them about changes to, expansions of, etc. your topic. Academic supervisors might do some of the following:

- Talk through whether the subject matter is suitable for your own skill set;

- Indicate if they are happy to work with you on your chosen topic;

- Advise you on the availability of information and resources on your topic, or if any problems are likely to arise;

- Help you to shape/refine your hypothesis or question.

Supervisors vary in how directive they get with student projects: there are many valid approaches to supervision. However, if you are ever concerned about the supervision you're receiving, consider discussing this with your Personal Academic Tutor.

In any case, you should not expect your academic supervisor to simply give you a 'good topic' – learning to develop research questions is a vital part of independent study, so while it can take trial and error, the process is worth it to improve as a scholar in your field.

From topic to hypothesis/question

Once you have decided upon the general topic and the main issues you wish to address, then you can think about developing your hypothesis or question in a more detailed way. Hypotheses need to be carefully phrased as the wording is an indication of what will be discussed in your essay. The hypothesis not only gives the reader information about the content you will write about, but also how you will approach the topic.

We'll explore an organised way to begin developing your hypothesis/question on the next tab.

Developing your hypothes(es) or question(s)

In developing your hypothesis or question, experiment with starting broad and gradually narrowing the focus. Work through the sequence of questions below to begin:

What subject?

What general field of study do you want to cover in the course of your research and writing? In some cases, this is self-evident: 'I'm a Biology student, so I'll cover Biology, of course.' However, some projects lend themselves to an interdisciplinary approach, meaning you will link or combine multiple subjects. For example...

- The fields of Medicine and Philosophy intersect when considering medical ethics, which could raise an initial question such as, ‘What are the ethical dimensions of denying NHS treatment on account of lifestyle choices?’

- The fields of History, Linguistics, and Queer Studies might intersect in undertaking an analysis of letters written between same-sex couples in the late 1800s.

Inventory your research interests and assess whether they nest neatly inside one discipline or are interdisciplinary in nature.

What theme?

- For the fields of History, Government and Politics, you could look at a theme such as U.S. foreign policy.

- For the field of Biomedical Engineering, you could look at the theme of smart prosthetics.

- For the field of Marketing, you could look at the theme of multi-channel retailing.

What context?

The themes above are too wide to tackle in a single piece of research. For example, 'U.S. foreign policy' could cover a ~250-year period that spans American relationships with nearly 200 different countries: that's too much! Therefore, the next step is to pick a context for your theme. For example...

- U.S. foreign policy as related to Iran in the twenty-first century.

- Smart prosthetics used by individuals with acquired lower-limb shortening.

- Multi-channel retailing among organic food brands in the UK.

As you can see, this context step continues to narrow down the focus of the initial subject and theme.

What specific angle?

Here, you will carefully consider the theme and its context, and ask yourself, 'What, specifically, is relevant to find out about this theme?' Or, put another way, what do you want to discover? The answers to questions like these will suggest a meaningful angle for your project. For example...

- Question: What role did the U.S. play in the 2009 Iranian elections?

- Hypothesis: Lower-limb prosthetic sockets could be redesigned with innovative materials to improve shock absorption and, thus, user comfort.

- Question: Which marketing channels are proving most effective for customer acquisition amongst organic food brands currently operating in the UK?

Bear in mind that longer projects such as dissertations and theses often address a handful of related questions – so don't panic if you can't boil it down to just one question!

What method(ology)?

Finally, it's time for a reality check: your idea might be fantastic, but is there a realistic way to produce meaningful answers? For example, this is an intriguing question:

Leading up to the 2016 Brexit vote, to what extent did the privately expressed opinions of top officials in the UK government align with, or contradict, their publicly made statements?

However intriguing that question, it would be difficult or impossible to research: how would you gather evidence of 'privately expressed opinions' in an ethical, reliable way? (Hacking governmental memos or email accounts definitely runs afoul of academic responsibility and conduct!)

Therefore, you need to vet whether a sound method or methodology can underpin your choice of theme(s), context and angle(s). You don't need to define every detail of your method at this stage, but ask yourself questions like these:

- For example, is it possible to compare and contrast the official responses of the U.S. and Iranian governments by using public speeches? Is there any further evidence of American involvement in the election highlighted in press reports, or online sources such as YouTube and Twitter? Which sources can you use to confirm facts, and which to confirm public perceptions/opinions?

- For example, have any organic food brands published their data on customer acquisition strategies? If not, how could you measure this using publicly available information and/or direct correspondence with brands?

- Identifying an ethical consideration doesn't necessarily mean you need to abandon your idea, but you will need to review the University Ethics Policy , discuss your idea with your supervisor, and, if deemed necessary, apply for ethics approval before proceeding.

The benefits

If you write a well considered hypothesis or question you can:

- Narrow your research and focus more carefully;

- Make better choices for the selection of your reading;

- From your reading you can select information more carefully and get the right evidence to include in your essay/project;

- Structure your writing to address the question(s) more directly;

- Transform your original hypothesis into a final thesis statement that frames your writing: see our Crafting the Introduction guide for more on thesis statements.

Refine and shine

All activities within the writing process are iterative: that is, you have to go through multiple versions (i.e., iterations) of what you're producing in order to improve it. In fact, your research questions may continue to evolve even once the research is underway. Such evolution is normal, so don't panic if you start to doubt your hypothesis halfway through writing up your work. Instead, use your growing knowledge base and new insights to make informed changes to your question(s) or hypothes(es).

Below, we'll work through some examples of ways that research questions might shift or be improved.

Think argument

It is essential that you can clearly develop an argument from the hypothesis or question that you pose. Avoid generalisations that are not possible to substantiate, for example...

Bad: The relationship between humanity and nature.

What is this trying to talk about? It could cover so many different topics and subjects that it needs to be much more focused. A better question would target specific relations between humanity and nature, for example...

Better example: Has humanity overcome the threat of earthquakes through its specially engineered buildings?

- This question would examine mankind’s relationship with nature in light of geological factors.

- However, while this question is better than the 'bad' original, it could be further improved – more on that shortly!

Avoid the yes/no trap

Let's return to the question above and consider the type of answer that its phrasing invites:

Has humanity overcome the threat of earthquakes through its specially engineered buildings?

In this case, the wording used encourages a response of either 'yes' or 'no' – either 'yes,' humanity has overcome the threat entirely (hurrah!), or 'no,' engineering has done nothing to stop the threat (boo!). However, the situation is surely more complex than that. A yes/no framing is therefore a poor foundation for the research, as it might compel the writer to sacrifice critical nuance in favour of a straightforward answer.

What if the writer were instead to consider phrasing options like these?

To what extent do specially engineered buildings mitigate the threat of earthquakes in major cities?

Which innovations in building design have proved most effective in reducing human casualties during earthquakes?

How can buildings be reengineered to minimise the threat to life posed by earthquakes?

These iterations of the question might not be perfect, but notice how they encourage greater complexity of response. The writer has moved away from a yes/no framing to instead pose questions that will allow richer, more layered answers to be explored in the body of the essay or project.

Is yes/no ever okay?

In short, yes – this is sometimes okay. However, you should treat any yes/no question with caution. In many cases, a yes/no question functions better when paired with or embedded within a question of more nuanced phrasing. For example...

Could polymer XYZ be replaced with polymer ABC in the manufacture of technology Q? If so, what implications exist for the cost and longevity of the final product?

Here, the first question is yes/no in nature – and for some assessment types, it might be sufficient! However, the second question builds upon the first to add more depth and relevance.

Expect detours

In many cases, research questions must be refined not because they are 'bad' or problematic, but instead due to either 1) evolution of interests/knowledge or 2) change(s) in research circumstances. The prior can loosely be understood as internally driven whilst the latter is externally driven. The examples below illustrate how these shifts might look in practice.

Evolution of interests/knowledge

Sam plans to critically evaluate the TV show The Walking Dead through the lens of disability theory in their dissertation. They begin the project with a set of related research questions that includes this one:

How do depictions of facial differences (e.g. scars, burns) in The Walking Dead reinforce – or alternately, subvert – the damaging trope of the 'Disabled Villain'?

This question operates well alongside Sam's other enquiries/hypotheses, and they make a strong start on their research. However, the deeper Sam gets into their analysis, the more they find themself writing about the show's depictions of amputations and prostheses rather than facial differences. Therefore, Sam decides to revise the focal question as so:

To what extent does loss of limbs operate as a metaphor for change to internal character throughout The Walking Dead, and do these depictions cumulatively serve to reify or subvert persistent tropes of disability in filmed media?

In this manner, Sam refined their research question to respond to an evolution of interest as well as their expanding knowledge of the source material. The 'detour' was internal as Sam didn't technically need to change directions, but by realigning the question with what they are actually curious about, the resulting dissertation will surely be richer.

Change(s) in research circumstances

The more panic-inducing 'detours' are those compelled by external change over which the writer has little or no control. Circumstantial changes that might impact the feasibility of your research question(s) include things like the following (click each dropdown heading to see examples):

Access to required data

- Problem: You intended to analyse items held overseas in a historical archive. However, your funding request to visit the archive was rejected, and the archive curators say they can't digitise the items for you.

- Potential solution: Can you conduct an equivalent analyis of items held in an archive you can access? For example, an archive maintained by a UK library or university, or an international archive that has already been digitised?

Availability of collaborators/partners for the research

- Problem: You intended to test the efficiency of a water filtration design by partnering with someone whose engineering specialty fills a vital gap in your abilities. However, they bail. You can't produce the whole filtration system on your own.

- Potential solutions: Could your supervisor help you find an appropriate collaborator to backfill the one who bailed? If not, could you test the design using computer modelling rather than building it 'IRL'? Alternately, could you test the durability, environmental friendliness, etc. of the design element you can produce rather than testing the efficiency of the entire system?

Current events

- Problem: Your MA is intended to culminate in a fieldwork experience during the spring of your degree. The fieldwork will underpin your entire dissertation. Unfortunately, conflict emerges in the geographical area of your planned fieldwork, and you can't safely proceed with traveling/working there.

- Potential solutions: In this case, your supervisor should definitely help you figure out an alternate plan! You might need to engage in fieldwork in a different area entirely, which will of course changes the precise question(s) you're asking. Alternately, your supervisor might encourage you to work with existing literature/data rather than gathering new data in the field.

A change to the feasibility of your method(ology) doesn't always mean you need to abandon your research question(s). If your question relates to the concept of customer satisfaction, for example, there could be many valid ways to measure and interpret that central concept.

If a circumstantial change pushes your plan off course, think creatively and think widely about potential solutions. And if this happens whilst tackling your dissertation or thesis, contact your supervisor ASAP to arrange a meeting.

The role of sub-questions

Finally, understand that you may need to ask (and answer) additional questions in order to address your central question: this is especially true of dissertations and theses. Think of these additional enquiries as sub-questions. Let's return to Sam's original research question from earlier:

This is phrased as one question, but let's slow down and consider how Sam can satisfactorily answer that central question. To provide rich, nuanced answers, Sam might actually need to ask a series of questions that build upon one another:

- How is the trope defined, discussed, etc. across research in Disability Studies?

- How is the trope defined, discussed, etc. across research in Film Studies?

- Are certain facial differences (e.g. a missing eye, a prominent scar) ascribed more often to certain character archetypes?

- Finally, having explored the above, how do depictions of facial differences in The Walking Dead serve to reinforce or subvert the trope of the 'Disabled Villain'?

Sam won't necessarily use the same method or approach to answer each question. For instance...

- Sam will likely review and synthesize existing literature from the fields of Disability Studies and Film Studies to answer the first sub-question.

- To answer the second sub-question, Sam will engage in close viewing and interpretation of the TV show.

- Finally, to answer the overarching question, Sam will use relevant theory as a lens to frame their firsthand textual analysis of the TV show, thereby drawing original conclusions.

Therefore, as you refine your research question, consider building out a mind map or bulleted list of the implied questions that underpin your main enquiry. Making these sub-questions explicit in the writing can help ensure the research proceeds in a logical way from A to B, B to C, etc.

Verbs are vital

Essay questions/titles provided by module leads usually hinge around one or more specific verb(s): that is, action word(s) or instruction(s) of what to do, e.g. 'Discuss,' 'Explain,' 'Evaluate,' etc. For example, imagine Daria's module lead has issued this essay prompt:

Instructor's prompt: 'Trace the evolution of rotor designs in functional helicopters from 1940 onward.'

Daria considers the prompt and her research interests, and she comes up with this hypothesis to kickstart her writing:

Hypothesis: 'In contemporary helicopters, height-based and weight-based adjustments to rotor blades minimize vibration in order to prevent stalling and ensure safe flights.'

Okay, perhaps that's true, but can you see the problems? First, Daria's hypothesis reads more as a statement of fact than a focusing concept for an essay – it's hard to tell what Daria plans to actually do in the writing. Second, Daria has ignored the key verb in the prompt, which was 'trace' – this means she should follow the development of rotor designs over time rather than comparing designs of the present day.

But what if you are designing your own essay/dissertation question or hypothesis rather than following an instructor's prompt?

Picking your own verbs

Essay verbs are every bit as vital when designing our own research questions and hypotheses! You will need to think about these words and their usage, as they will indicate what is to come in your essay or dissertation. For example, imagine you write that you will 'analyse' a situation, but then your essay simply 'summarises' the situation.

- The verb 'analyse' suggests that you will describe the main ideas in depth, showing why they are important, how they are connected, etc. in a critical manner.

- The verb 'summarise' means that you will offer a concise account of main points without critical elaboration.

The mismatch between what you stated you would do and what you actually delivered will likely compel the marker to assign a lower mark to your work.

In the context of a dissertation or thesis , you are likely to use multiple verbs to describe what you will do, given the complexity of the work at hand. These typically appear in your introduction as well as the opening paragraphs of your individual chapters, e.g. 'This chapter will first define condition ABC and then compare divergent perspectives on its treatment.'

– Need a hand understanding the verbs you can choose from and which is the best fit? Check out the 'The Verb' tab of our Understanding the Assignment guide for a comprehensive list.

When you have posed your hypothesis or question, check your department’s guidelines:

- How long should the assignment be?

- What is the deadline?

- What other requirements are there (presentation, referencing, bibliography, etc.)?

Basic research

Start with basic reading to get an overview of the topic and the current issues surrounding it. Keep the question in mind as you do your initial research:

- Lecture and seminar notes.

- Relevant chapters in core textbooks.

- Frequently cited and recent articles.

- Websites: The internet is a hugely valuable resource for research, but remember to verify that the information you have located is academically reliable.

You can think of this first research phase as 'dipping your toes in the water.' It's helpful to get a sense of the overall landscape before investing too much time unpicking highly complex, sprawling literature.

Detailed research

When you are familiar with the basics, move on to more advanced texts where you will find detail on the variety of academic opinions on a given topic and suitable supporting evidence:

- Articles in academic journals (use your Library Search account to get started).

- Texts referred to by your lecturers or supervisor.

- References in core texts (you can expand your reading by checking footnotes, endnotes and bibliographies of core texts to find related work and sources).

- General and specialist databases (check your Library subject page for databases suggested for your discipline).

Be selective

It is essential to always make sure your examples are relevant to the topic in hand. Keep the question in mind, and check the relevance of the material you read and note down.

- << Previous: Overview and Planning

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2024 3:53 PM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/writing_the_dissertation

🚀 Work With Us

Private Coaching

Language Editing

Qualitative Coding

✨ Free Resources

Templates & Tools

Short Courses

Articles & Videos

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

T he research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

You Might Also Like:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Dissertation While Working: A How-To Guide

Struggling to balance your dissertation with a full-time job and family? Learn practical strategies to achieve success.

How To Review & Understand Academic Literature Quickly

Learn how to fast-track your literature review by reading with intention and clarity. Dr E and Amy Murdock explain how.

Dissertation Writing Services: Far Worse Than You Think

Thinking about using a dissertation or thesis writing service? You might want to reconsider that move. Here’s what you need to know.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

41 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

This is a well researched and superbly written article for learners of research methods at all levels in the research topic from conceptualization to research findings and conclusions. I highly recommend this material to university graduate students. As an instructor of advanced research methods for PhD students, I have confirmed that I was giving the right guidelines for the degree they are undertaking.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

Dissertations & projects: Research questions

- Research questions

- The process of reviewing

- Project management

- Literature-based projects

Jump to content on these pages:

“The central question that you ask or hypothesis you frame drives your research: it defines your purpose.” Bryan Greetham, How to Write Your Undergraduate Dissertation

This page gives some help and guidance in developing a realistic research question. It also considers the role of sub-questions and how these can influence your methodological choices.

Choosing your research topic

You may have been provided with a list of potential topics or even specific questions to choose from. It is more common for you to have to come up with your own ideas and then refine them with the help of your tutor. This is a crucial decision as you will be immersing yourself in it for a long time.

Some students struggle to find a topic that is sufficiently significant and yet researchable within the limitations of an undergraduate project. You may feel overwhelmed by the freedom to choose your own topic but you could get ideas by considering the following:

Choose a topic that you find interesting . This may seem obvious but a lot of students go for what they think will be easy over what they think will be interesting - and regret it when they realise nothing is particularly easy and they are bored by the work. Think back over your lectures or talks from visiting speakers - was there anything you really enjoyed? Was there anything that left you with questions?

Choose something distinct . Whilst at undergraduate level you do not have to find something completely unique, if you find something a bit different you have more opportunity to come to some interesting conclusions. Have you some unique experiences that you can bring: personal biography, placements, study abroad etc?

Don't make your topic too wide . If your topic is too wide, it will be harder to develop research questions that you can actually answer in the context of a small research project.

Don't make your work too narrow . If your topic is too narrow, you will not be able to expand on the ideas sufficiently and make useful conclusions. You may also struggle to find enough literature to support it.

Scope out the field before deciding your topic . This is especially important if you have a few different options and are not sure which to pick. Spend a little time researching each one to get a feel for the amount of literature that exists and any particular avenues that could be worth exploring.

Think about your future . Some topics may fit better than others with your future plans, be they for further study or employment. Becoming more expert in something that you may have to be interviewed about is never a bad thing!

Once you have an idea (or even a few), speak to your tutor. They will advise on whether it is the right sort of topic for a dissertation or independent study. They have a lot of experience and will know if it is too much to take on, has enough material to build on etc.

Developing a research question or hypothesis

Research question vs hypothesis.

First, it may be useful to explain the difference between a research question and a hypothesis. A research question is simply a question that your research will address and hopefully answer (or give an explanation of why you couldn't answer it). A hypothesis is a statement that suggests how you expect something to function or behave (and which you would test to see if it actually happens or not).

Research question examples

- How significant is league table position when students choose their university?

- What impact can a diagnosis of depression have on physical health?

Note that these are open questions - i.e. they cannot be answered with a simple 'yes' or 'no'. This is the best form of question.

Hypotheses examples

- Students primarily choose their university based on league table position.

- A diagnosis of depression can impact physical health.

Note that these are things that you can test to see if they are true or false. This makes them more definite then research questions - but you can still answer them more fully than 'no they don't' or 'yes it does'. For example, in the above examples you would look to see how relevant other factors were when choosing universities and in what ways physical health may be impacted.

For more examples of the same topic formulated as hypotheses, research questions and paper titles see those given at the bottom of this document from Oakland University: Formulation of Research Hypothesis

Which do you need?

Generally, research questions are more common in the humanities, social sciences and business, whereas hypotheses are more common in the sciences. This is not a hard rule though, talk things through with your supervisor to see which they are expecting or which they think fits best with your topic.

What makes a good research question or hypothesis?

Unless you are undertaking a systematic review as your research method, you will develop your research question as a result of reviewing the literature on your broader topic. After all, it is only by seeing what research has already been done (or not) that you can justify the need for your question or your approach to answering it. At the end of that process, you should be able to come up with a question or hypothesis that is:

- Clear (easily understandable)

- Focused (specific not vague or huge)

- Answerable (the data is available and analysable in the time frame)

- Relevant (to your area of study)

- Significant (it is worth answering)

You can try a few out, using a table like this (yours would all be in the same discipline):

A similar, though different table is available from the University of California: What makes a good research topic? The completed table has some supervisor comments which may also be helpful.

Ultimately, your final research question will be mutually agreed between yourself and your supervisor - but you should always bring your own ideas to the conversation.

The role of sub-questions

Your main research question will probably still be too big to answer easily. This is where sub-questions come in. They are specific, narrower questions that you can answer directly from your data.

So, looking at the question " How much do online users know and care about how their self-images can be used by Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook? " from the table above, the sub-questions could be:

- What rights do the terms and conditions of signing up for Apple, Google, Microsoft and Facebook accounts give those companies regarding the use of self-images?

- What proportion of users read the terms and conditions when creating accounts with these companies?

- How aware are users of the rights they are giving away regarding their self-images when creating accounts with these companies?

- How comfortable are users with giving away these rights?

Together, the answers to your sub-questions should enable you to answer the overarching research question.

How do you answer your sub-questions?

Depending on the type of dissertation/project your are undertaking, some (or all) the questions may be answered with information collected from the literature and some (or none) may be answered by analysing data directly collected as part of your primary empirical research .

In the above example, the first question would be answered by documentary analysis of the relevant terms and conditions, the second by a mixture of reviewing the literature and analysing survey responses from participants and the last two also by analysing survey responses. Different projects will require different approaches.

Some sub-questions could be answered by reviewing the literature and others from empirical study.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Nov 10, 2024 5:39 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/dissertations

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Learn how to turn a weak research question into a strong one with examples suitable for a research paper, thesis or dissertation.

Here are the most common questions we hear about writing dissertations and earning your doctorate. 1. What is a dissertation? A dissertation is a published piece of academic research. Through your dissertation research, you become an expert in a specific academic niche.

This National Dissertation Day, we asked our dissertation advisers to answer some of the most common questions they get asked by students. These range from what you need to know before you start, tips for when you’re writing, and things to check when you’ve finished.

During this meeting, we would suggest that you: (a) determine whether your research design, research method and sampling strategy are sufficient; (b) get advice on whether your research strategy is likely to be achievable in the time you have available; (c) check that your research strategy meets your dissertation and university's ethical guidel...