Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Informatics Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Community Medicine, International Medical School, Management and Science University, Shah Alam, Malaysia, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Asia Metropolitan University, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department: School of Criminal Justice Education, Institution: J.H. Cerilles State College, Caridad, Dumingag, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia, South East Asia Community Observatory (SEACO), Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

- Ken Brackstone,

- Roy R. Marzo,

- Rafidah Bahari,

- Michael G. Head,

- Mark E. Patalinghug,

- Published: October 19, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, large-scale vaccination coverage is crucial to the national and global pandemic response, especially in populous Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines and Malaysia where new information is often received digitally. The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify individual, behavioural, or environmental predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Data from an internet-based cross-sectional survey of 2558 participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) and Malaysia ( N = 1556) were analysed. Results showed that Filipino (56.6%) participants exhibited higher COVID-19 hesitancy than Malaysians (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants ( p = 0.105). Predictors associated with vaccine hesitancy among Filipino participants included women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.03–1.83; p = 0.030) and rural dwellers (OR, 1.44, 95% CI, 1.07–1.94; p = 0.016). Among Malaysian participants, vaccine hesitancy was associated with women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.14–1.99; p = 0.004), social media use (OR, 11.76, 95% CI, 5.71–24.19; p < 0.001), and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.48, 95% CI, 1.72–3.58; p < 0.001). Predictors associated with vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included subjective social status (OR, 1.13, 95% CI, 1.54–1.22; p < 0.001), whereas vaccine confidence among Malaysian participants was associated with higher education (OR, 1.30, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p < 0.028) and negatively associated with rural dwellers (OR, 0.64, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.005) and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.57; p < 0.001). Efforts should focus on creating effective interventions to decrease vaccination hesitancy, increase confidence, and bolster the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination, particularly in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Citation: Brackstone K, Marzo RR, Bahari R, Head MG, Patalinghug ME, Su TT (2022) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(10): e0000742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

Editor: Nnodimele Onuigbo Atulomah, Babcock University, NIGERIA

Received: June 12, 2022; Accepted: September 20, 2022; Published: October 19, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Brackstone et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data are available on the OSF repository: https://osf.io/ncwjq/ .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

While many high-income settings have achieved relatively high coverage with their COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, almost 32.1% of the world’s population have not received a single dose of any COVID-19 vaccine as of July 2022 [ 1 ]. The Philippines and Malaysia are among two of the most populous countries in Southeast Asia with an estimated population of 110 million and 32 million people, respectively. To date, Malaysia has seen over 4.6 million cases with a mortality rate of 0.77%, while approximately 3.7 million cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.60% [ 2 ]. Malaysia is doing considerably well with their vaccination efforts, with 84.8% of the population currently considered fully vaccinated as of July 2022. However, vaccination campaigns in the Philippines have been more difficult, with 65.6% of the population fully vaccinated [ 3 ]. With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant across the world [ 4 ], large-scale vaccination coverage remains fundamental to the national and global pandemic response. Regular scientific assessments of factors that may impede the success of COVID-19 vaccination coverage will be critical as vaccination campaigns continue in these nations.

A key factor for the success of vaccination campaigns is people’s willingness to be vaccinated once doses become accessible to them personally. Vaccine hesitancy is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the delay in the acceptance, or blunt refusal of, vaccines. In fact, vaccine hesitancy was described by the WHO as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019 [ 5 ]. Conversely, vaccine confidence relates to individuals’ beliefs that vaccines are effective and safe. In general, a loss of trust in health authorities is a key determinant of vaccine confidence, with misconceptions about vaccine safety being among the most common reasons for low confidence in vaccines [ 6 ].

Previously, vaccination in Southeast Asia has been associated with mistrust and fear, particularly in the Philippines, who are still suffering the consequences of the Dengvaxia (dengue) vaccine controversy in 2017 [ 7 ]. Studies suggest that this highly political mainstream event, in which anti-vaccination campaigns linked dengue vaccines with autism spectrum disorder and with corrupt schemes of pharmaceutical companies, continue to erode the population’s trust in vaccines. For example, a survey conducted on over 30,000 Filipinos in early 2021 showed that 41% of respondents would refuse the COVID-19 vaccine once it became available, whereas Malaysia reported 27% hesitancy [ 8 ]. Researchers predict that the controversy surrounding Dengvaxia may have prompted severe medical mistrust and subsequently weakened the public’s attitudes toward vaccines [ 7 , 9 ]. However, there may be many additional factors that weaken confidence in vaccines. For example, incompatibility with religious beliefs is one key driver of weakened confidence in vaccines [ 10 , 11 ], whereas living in urbanised (vs. rural) areas predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in some countries [ 12 – 14 ], possibly due to being more connected to the internet and social media and being more exposed to COVID-19-related misinformation.

Other predictors of vaccine hesitancy and confidence may include digital health literacy–one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources–and social media use. Research has shown that beliefs in available information is integral to perceptions of the vaccine safety and effectiveness [ 15 – 17 ]. Previous studies, for example, have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines, particularly if they relied on social media as a key source of information [ 18 , 19 ]. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is a widely accepted theory which may explain individual behaviors, including digital health literacy [ 20 ]. SCT consists of three factors–environmental, personal, and behavioural–and any two of these components interact with each other and influence the third. As such, SCT can assist in establishing a link between one’s behaviour (e.g., information-seeking–one form of digital health literacy) and environmental factors (e.g., availability of information online), which may interact to promote medical mistrust and influence vaccine hesitancy and confidence (personal) [ 21 ]. Thus, health behaviours are often influenced by social systems as well as personal behaviours.

Although vaccine hesitancy and confidence are related concepts (e.g., people who express low confidence in vaccines are more likely to be vaccine-hesitant [ 6 ]), they are also distinct [ 22 ]. Thus, the main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with both outcomes. Thus, developing a deeper understanding of the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and confidence will provide insight into how specific population groups may respond to health threats and public health control measures.

Design, subjects, and procedure

This was an internet-based cross-sectional survey conducted from May 2021 to September 2021 in the Philippines and Malaysia. Snowball sampling methods were used for the data collection using social media, including research networks of universities, hospitals, friends, and relatives. Filipino and Malaysian residents aged 18 years or older were invited to take part. The inclusion criteria for participants’ eligibility included 18 years or older, and an understanding of the English language. All invited participants consented to the online survey before completion. Consented participants could only respond to questions once using a single account. The voluntary survey contained a series of questions which assessed sociodemographic variables, social media use, digital literacy skills in health, and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from Asia Metropolitan University’s Medical Research and Ethics Committee (Ref: AMU/FOM/MREC 0320210018). All participants provided informed consent. All study information was written and provided on the first page of the online questionnaire, and participants indicated consent by selecting the agreement box and proceeding to the survey.

Demographics.

Filipino and Malaysian participants indicated their age category (18–24, 25–34, or 35–44), gender (man, woman), community type (rural, urban), educational level (no formal education, primary, secondary, tertiary), employment (unemployed, part-time, full-time), religion (Christian, Buddhism, Muslim, Hinduism, Other, None), income (1 = very insufficient ; 4 = very sufficient ; M = 1.84, SD = 0.81), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (no vs. yes), and whether they were social media users (no vs. yes).

Subjective social status.

Participant then rated their own perceived social status using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status scale [ 23 ]. Participants viewed a drawing of a ladder with 10 rungs, and read that the ladder represented where people stand in society. They read that the top of the ladder consists of people who are best off, have the most money, highest education, and best jobs, and those at the bottom of the ladder consists of people who are worst off, have the least money, lowest education, and worst or no jobs. Using a validated single-item measure, participants placed an ‘X’ on the rung that best represented where they think they stood on the ladder (1 = lowest ; 10 = highest; M = 6.23, SD = 1.86).

Vaccine confidence and hesitancy.

Participants were also asked about their perceived level of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine (“I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe,” 1 = strongly disagree ; 7 = strongly agree; M = 4.57, SD = 1.48). Then, participants were asked about their level of hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine (“I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule”; no, I don’t know, yes). These questions were adapted from the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe survey [ 24 ]. The tool underwent evaluation by multidisciplinary panel of experts for necessity, clarity, and relevance.

Digital health literacy.

Finally, participants completed the Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) [ 25 ], which was adapted in the context of the COVID-HL Network. The scale measures one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources. A total of 12 items (three per each dimension) were asked, and answers were recorded on a four-point Likert scale (1 = very difficult ; 4 = very easy; α = .92; M = 2.15, SD = 0.59). While the original DHLI is comprised of 7 subscales, we used the following four domains, including: (1) information searching or using appropriate strategies to look for information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on coronavirus virus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to find the exact information you are looking for?”; α = .87; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (2) adding self-generated content to online-based platforms (e.g., “When typing a message on a forum or social media such as Facebook or Twitter about the coronavirus a related topic, how easy or difficult is it for you to express your opinion, thought, or feelings in writing?”; α = .74; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (3) evaluating reliability of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to decide whether the information is reliable or not?”; α = .86; M = 2.20, SD = 0.69), and (4) determining relevance of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to use the information you found to make decisions about your health [e.g., protective measures, hygiene regulations, transmission routes, risks and their prevention?”]; α = .87; M = 2.09, SD = 0.68). The reliability statistics for the overall DHL score was 0.92, while the alpha coefficients for the four subscales ranged from 0.74 to 0.87, suggesting acceptable to good internal consistency.

Data analysis

Data were examined for errors, cleaned, and exported into IBM SPSS Statistics 28 for further analysis. All hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 0.05. χ 2 tests were conducted for group differences of categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables. Subgroup analyses were performed for Filipino and Malaysian participants.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence were treated as separate dependent variables in a logistic regression model providing the strictest test of potential associations with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence among Filipino and Malaysian participants. Low vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses to the statement: “I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe” into those who disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed (1–4), whereas high vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses into those who agreed to some extent (5–7). Vaccine hesitancy was operationalised by dichotomising responses to the statement: “I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the National vaccination schedule” into those indicating ‘no’ or ‘I don’t know,’ whereas no vaccine hesitancy was operationalized by dichotomising participants’ response into those who indicated ‘yes.’

Independent variables were: age (18–24 vs. 25–34 vs. 35–44 [ref]), gender (women vs. men [ref]), community type (rural vs. urban [ref]), educational level (tertiary vs. secondary or less [ref]), employment (employed to some degree vs. unemployed [ref]), religion (Philippines: Christianity vs. Islam [ref]; Malaysia: Christianity vs. Buddhism vs. Hinduism vs. Islam [ref]), income (low (1–2) vs. high (3–4 [ref])), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (yes vs. no [ref]), whether they were social media users [yes vs. no [ref]), their perceived ranking on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (continuous variable), and finally the four domains of the DHLI scale (all continuous variables).

A total of 2558 participants completed the online survey. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) vs. Malaysia ( N = 1556). Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants indicated higher rates of education ( p < 0.001), but were more likely to be unemployed ( p < 0.001). Further, Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants were also more likely to indicate lower income ( p < 0.001) and rate themselves lower on subjective social status ( p < 0.001). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were more likely to live in urban areas ( p < 0.001). Most notably, Filipino participants (56.6%) indicated higher prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy compared to Malaysian participants (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants in ratings of vaccine confidence ( p = 0.105). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were also more likely to report using social media (96.6 vs. 89.8%; < 0.001).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Values are presented as percent (n) or means ± SD.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t001

Table 2 shows significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Among Filipino participants, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that factors associated with higher vaccine hesitancy included women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), residing in a rural community (OR, 1.45, 95% CI, 1.07–1.95; p = 0.015), and having lower income (OR, 1.62, 95% CI, 1.20–2.19; p = 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), being aged 25–34 (vs. 18–24; OR, 1.52, 95% CI, 1.48–2.21; p = 0.027), Christians (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 1.66–3.62; p < 0.001), completing tertiary education (OR, 2.17, 95% CI, 1.63–2.88; p < 0.001), social media use (OR, 11.59, 95% CI, 5.63–23.84; p < 0.001), and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.50, 95% CI, 1.74–3.61; p < 0.001) were predictors of higher vaccine hesitancy, whereas having a health impairment (OR, 0.49, 95% CI, 0.30–0.78; p = 0.003) and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.75–0.89; p < 0.001) were associated with lower vaccine hesitancy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t002

Table 3 shows significant predictors of vaccine confidence in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.16, 95% CI, 1.07–1.25; p < 0.001), whereas factors associated with lower vaccine confidence included women (OR, 0.72, 95% CI, 0.54–0.96; p = 0.026) and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.49–0.81; p < 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence included women (OR, 1.27, 95% CI, 1.18–1.60; p = 0.035), completing tertiary education (OR, 1.31, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p = 0.026), and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.00–1.16; p = 0.036). Factors negatively associated with lower vaccine confidence included residing in a rural community (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.004), Christians (OR, 0.50, 95% CI, 1.20–2.24; p < 0.001), Buddhists (OR, 0.15., 95% CI, 0.10–0.22; p < 0.001), Hindus (OR, 0.24., 95% CI, 0.17–0.34; p = 0.004), information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.58; p < 0.001), and determining relevance of online information (OR, 0.68, 95% CI, 0.51–0.92; p = 0.013).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t003

Malaysia and the Philippines are among the most populous countries in Southeast Asia. While the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been permanent in the Philippines, it has been shown thus far to be temporary in Malaysia [ 26 ]. Between January and October 2020, around 30,000 Malaysians had been infected by the virus with a mortality rate of 0.79%, while approximately 380,000 cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.9% [ 2 ]. Further, 61.8% of Malaysians had completed their vaccination up until September 2021, while the percentage of completed vaccinations during the same period in the Philippines was only 19.2% [ 27 ]. Vaccine uptake is likely to be a key determining factor in the outcome of a pandemic. Knowledge around factors which predict vaccine hesitancy and confidence is of the utmost important in order to improve vaccination rates. Thus, the core aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with these outcomes.

First, while there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine between Filipino and Malaysian participants, Filipino (compared to Malaysian) participants expressed greater vaccine hesitancy. This may be a consequence of previous vaccine scares in the years leading up to the pandemic, including the Dengvaxia controversy in 2016 [ 7 , 9 ]. Systematic reviews demonstrated that, by the end of 2020, the highest vaccine acceptance was in China, Malaysia, and Indonesia [ 28 , 29 ]. The authors postulated that this elevated awareness was due to being among the first countries affected by the virus, hence resulting in greater confidence in vaccines [ 28 ].

Next, this study shows that women expressed greater vaccine hesitancy in both countries. The evidence base shows mixed findings, with other studies reporting higher hesitancy in women [ 30 ] or in men [ 31 ]. In some countries, the gender gap is not as substantial as others. In a large global study conducted in countries such as Russia and the United States, it was found that there is greater gender gap in vaccine hesitancy among men and women compared to countries such as Nepal and Sierra Leone [ 32 , 33 ]. Unsurprisingly, what drives this hesitancy is the inclusion of pregnant women, where studies have consistently demonstrated that this population is more hesitant toward vaccination due to concerns for their babies [ 34 ]. Hence, after taking all consideration into account, gender differences in vaccine hesitancy cannot be supported with certainty. This also emphasises the need for tailored health promotion towards the key populations at risk.

There are clear differences in predictors of vaccine hesitancy in the Philippines and Malaysia. However, when results for both countries were combined, women, urban dwellers, those of Christian faith, those with higher educational attainment, higher self-reported social class, social media use, and information-seeking tendencies remained as predictors of hesitancy. Urban-dwellers and individuals with more years of education have previously been demonstrated as predictors for vaccine hesitancy [ 35 ], but contradictory results have also previously been shown [ 36 , 37 ]. Urban residents are typically more connected to the internet and social media and, thus, may be more exposed to vaccine-related misinformation than rural inhabitants who have fewer sources of information available to them [ 12 – 14 ]. Nevertheless, reports have shown higher vaccine refusals among those with strong religious beliefs such as the Amish Community in the United States and the Orthodox Protestants in the Netherlands [ 38 ], as well as some Muslim groups in Pakistan [ 18 ].

Frequent social media use is the only strong predictor for vaccine hesitancy in this study, followed by information-seeking behaviours. Research has identified that the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine is the primary concern that people have, including beliefs in available information [ 15 – 17 ]. Unfortunately, high internet literacy is a double-edged sword, since participants in this study preferred to seek information through social media, and thus may have been exposed to inaccurate information regarding COVID-19 vaccine. Previous studies have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines [ 18 ], particularly if they relied heavily on social media as a key source of vaccine-related information [ 19 ]. A 2022 systematic review discovered that high social media use is the main driver of vaccine hesitancy across all countries around the globe, and is especially prominent in Asia [ 39 ]. Furthermore, vaccine acceptance and uptake improved among those who obtained their information from healthcare providers compared to relatives or the internet [ 40 ].

In terms of vaccine confidence, our findings show that those with higher subjective social status have higher confidence in vaccination, consistent with previous studies describing how those with a higher income had expressed willingness to pay for their COVID-19 vaccination if necessary [ 32 , 41 , 42 ]. Further, those of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu faiths, as well as those with a tendency to seek out information, were associated with lower vaccine confidence. This is in keeping with the previous findings demonstrating that strong religious convictions are often tied to mistrust of authorities and beliefs about the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is fuelled by social media [ 43 ]. Furthermore, concern on the permissibility of these vaccines in their religion reduces its acceptability [ 10 ]. However, it is interesting to note that, while the majority in Malaysia are Muslims, it did not reduce the rate of vaccine acceptance and confidence in the country.

These findings have important implications for health authorities and governments in areas focusing on improving vaccination uptake. Misinformation about vaccination greatly hampers vaccination efforts. Thus, not only is it important to understand how specific population groups are influenced by digital platforms such as social media, but it is imperative to provide the right information driven by governmental and non-governmental organisations [ 39 ]. This could be achieved by having community-specific public education and role modelling from local health and public officials, which has been shown to increase public trust [ 44 ]. Since the primary reason for hesitancy is concern about the safety of vaccines, it is crucial that education programmes stress the effectiveness and importance of COVID-19 vaccinations [ 45 ]. Participants in this study coped with the pandemic by seeking out new information, but they sought information from social media when information from the authorities was lacking or were viewed as untrustworthy, which may have contained erroneous information. One way to deter this is to empower information-technology companies to monitor vaccine-related materials on social media, remove false information, and create correct and responsible content [ 44 ].

Furthermore, behavioural change techniques have been found to be useful in stressing the consequences of rejecting the vaccine on physical and mental health [ 46 ]. The most effective “nudging” interventions included offering incentives for parents and healthcare workers, providing salient information, and employing trusted figures to deliver this information [ 47 ]. Finally, since religious concerns have been prominent in reducing vaccine confidence and increasing hesitancy in this study, it is important to tailor messages to include information related to religion, and the use of religious leaders to spread these messages [ 48 ]. These are all important factors for increasing uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine, but also may be relevant in acceptability of routine immunisations as countries look to transition towards a post-pandemic delivery of healthcare.

A limitation of this study includes its cross-sectional design and the heterogeneity among participants, which meant that temporal changes in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines across time were not captured. Further, the need for internet access among Filipino and Malaysian participants limited the representativeness of the sample population. Thus, certain demographic were under-represented, including Filipino and Malaysian individuals over the age of 45, and people of lower socio-economic status. The surveys were also implemented in English, which may have limited the participation of target participants who were not fluent in English. In addition, due to space limitations, vaccine hesitancy and confidence were each captured using one item, which raises concerns of the items’ validity and reliability. Finally, not all independent variables were accounted for, including medical mistrust [ 49 ], vaccine knowledge [ 50 ], and specific social media platforms used [ 11 ]. We also did not assess whether participants had received any doses of the COVID-19 vaccine previously. Future research should include more important predictors to build a broader picture of vaccine-related hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia, and more items should be utilised to tap into these concepts more comprehensively. Despite these limitations, the core strength of this study relates to its relatively large number of participants from both countries, and its comprehensive analysis of predictors to provide as a starting point going forward.

Conclusions

The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among unvaccinated individuals in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Predictors of vaccine hesitancy in this study included the use of social media, information-seeking, and Christianity. Higher socioeconomic status positively predicted vaccine confidence. However, being Christian, Buddhist or Hindu, and the tendency to seek information online, were predictors of hesitancy. Efforts to improve uptake of COVID-19 vaccination must be centred upon providing accurate information to specific communities using local authorities, health services and other locally-trusted voices (such as religious leaders), and for the masses through social media. Further studies should focus on the development of locally-tailored health promotion strategies to improve vaccination confidence and increase the uptake of vaccination–especially in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Supporting information

S1 file. inclusivity in global research questionnaire..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.s001

- 1. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C,Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Philippines: Coronavirus pandemic country profile. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/philippines .

- 9. Mendoza RU, Valenzuela, S, Dayrit, M. A Crisis of Confidence: The Case of Dengvaxia in the Philippines. SSRN: doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3519736.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Junctures in the time of COVID-19: Topic search and government's framing of COVID-19 response in the Philippines

Rogelio alicor l panao, ranjit singh rye.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Rogelio Alicor L Panao, Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, 1101 Philippines. Email: [email protected]

Issue date 2023 Jun.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until permissions are revoked in writing. Upon expiration of these permissions, PMC is granted a perpetual license to make this article available via PMC and Europe PMC, consistent with existing copyright protections.

This article argues that, like many in Southeast Asia, the Philippine government's COVID-19 response was marked by policy experimentation and incremental adaptation, having been caught off-guard by the pandemic. Examining 16,281 government press releases related to COVID-19 issued by the Philippine News Agency between February 2020 and April 2021, we find that in its policy narratives the government panders initially to citizen demand, highlighting social amelioration as a pandemic strategy. However, as citizens’ economic anxiety further intensifies, the government's framing of the crisis response becomes pragmatic and turns towards promoting mass inoculation, ostensibly in a bid to convince citizens to choose health over short-term palliative economic measures. The findings nuance policymaking in an illiberal democracy, beyond the conventional populist description of seeking easy solutions or spectacularizing crisis response.

Keywords: COVID-19, critical juncture, Google Trends, Philippines, policy learning, vaccines

Just as prospects were getting rosy for the Philippine economy, bad news arrived. On January 22, 2020, the first COVID-19 infection in the Philippines was detected in two Chinese nationals visiting the country ( Edrada et al., 2020 ). On February 2, 2020, the first confirmed death due to the virus was reported ( Marquez, 2020 ). By March, the virus had taken the lives of 24 more additional patients and brought the number of cases to 380. By April that year, confirmed cases in the Philippines were running up to four digits.

The government's immediate response to the pandemic focused on minimizing its socioeconomic impact and restarting the economy. For instance, on March 23, 2021, Congress passed Republic Act 11469, the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, granting the president, inter alia, temporary emergency powers to impose community lockdowns and providing cash assistance to displaced workers and low-income families. Essentially a “social amelioration initiative,” the Bayanihan Act was a direct response to the World Health Organization's (WHO) recommendations ( Vallejo and Ong, 2020 ) to an economy thrown into its worst recession since the Second World War. While there were variations in subsequent implementing policies, within government the consensus seemed to have been towards balancing economic growth with public health. However, by the end of the first quarter of 2021, amidst a sudden surge in COVID-19 cases, the government's official policy response took a complete turn towards procuring ample vaccines and inoculating the public.

What causes policy response to turn from palliative interventions to pragmatic options? For resource-challenged governments conveying their policy narratives to the public in response to crises, what motivates the choice between economic viability and securing vaccines? Can citizens’ interest in an event or crisis spur policy learning amidst a lack of adequate opportunity to establish a response strategy?

This article argues that, like many in Southeast Asia, the Philippine government's COVID-19 response was marked by policy experimentation and incremental adaptation, having been caught off-guard by the pandemic. While it is well known in the public policy and political science literature that public opinion can shape public policy ( Wlezien and Soroka, 2016 ); the bulk of the literature is usually in the context of interest groups, political parties, and elites, not ordinary citizens, and not with respect to experiences outside the USA ( Burstein, 2003 ). As for the policy implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, on the other hand, the growing and emerging body of research is largely focused on epidemiological aspects such as the spread of the disease and compliance to health measures ( Brodeur et al., 2021 ). There is also scant scholarly introspection on causal explanations pertinent to the governance component of pandemic policies beyond an organizing framework ( Maor and Howlett, 2020 ).

Using the dynamics of the Philippine government's COVID-19 response as a case study, we argue that citizen concern on economic dislocations during the pandemic has a dynamic effect on how the government frames contentious policies whose redistributive implications can undermine government legitimacy. As anxious citizens seek information on the pandemic, the government panders to what it believes to be a response desired by the public and frames its COVID-19 policy around social assistance as a defining narrative. However, as mounting anxiety reveals the public's uncertainty with concurrent policy, the framing of the crisis response becomes rational and shifts towards the promotion of more viable options, such as mass inoculation. To support our conjecture, we analyzed 16,281 press releases on COVID-19 issued by the Philippine News Agency (PNA) between February 2020 and April 2021, and juxtaposed them with citizens’ COVID-19-related search interest based on Google Trends. Utilizing topic modeling and econometric techniques, we find that the government panders to citizen demand for economic safety nets in its policy narratives but only up to a point, and ultimately shifts to promoting mass inoculation as economic anxiety worsens.

The findings provide an evidence-based facet of policymaking in a precarious democracy criticized for lackluster pandemic intervention. The international media, for instance, initially branded the Philippine COVID-19 response a “tragedy of errors” ( Beltran, 2020 ). While there is arguably a basis for this view, our findings suggest nevertheless that there was an attempt by the government to be responsive, even if such responsiveness meant pandering to public sensitivities with respect to weighing policy alternatives. There was also policy learning, as shown by how the government pragmatically reoriented its policy narrative from economic support to mass inoculation, after heightened interest in social transfers made it realize that population immunity is more cost effective in the long run.

The article proceeds as follows. We begin by expounding on the relationship between crises and policy change as the focus of theoretical and empirical introspection in the literature. Afterwards, we elaborate on our theory explaining why the government's COVID-19 policies were shaped by policy adaptation and experimentation. We also explain why we expect informational citizenship to induce the government to turn from a reactive policy that is narrowly focused on providing economic assistance to one that targets population immunity. This is followed by a discussion of the data, measures, and estimation approach we employed to test our conjecture. We then discuss the results and how they nuance current understanding of the government response to the COVID-19 crisis. The article concludes with the broader implications of the findings on pandemic policymaking.

Policymaking and policy shifts

There is a policy change or shift when one that is existing is replaced with something new and innovative, or undertakes incremental refinements ( Bennett and Howlett, 1992 ). Political dynamics, problems, and proposal may be construed as streams capable of suddenly changing government policies ( Cairney and Jones, 2016 ). During crucial periods, these streams may create an opportunity or condition in which agenda change is possible. Referred to as policy windows, these critical junctures open an array of choices to policy actors, allowing decision making to become more significant ( Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007 ; Donnelly and Hogan, 2012 ). Punctuated equilibrium occurs when abrupt and radical policy changes arise after a long period of stability ( Jones and Baumgartner, 2012 ). Bennett and Howlett (1992) , for their part, argue that states learn from experiences and modify decisions based on how well previous measures performed in the past. This policy learning serves as a platform for future decisions and these are circulated as new information to achieve political goals and create policy-related beliefs over time ( Moyson et al., 2017 ).

There are competing views on policy learning but there is almost scholarly consensus regarding the role of social forces in policy change. An indication of learning happens when there is a shift in policy, even though the preferred policy is not necessarily the most efficient ( Hall, 1993 ). Sometimes the government learns simultaneously while responding to circumstances or crises through key societal actors who create conditions that state officials must address ( Bennett and Howlett, 1992 ). Policy learning, according to Greener (2002) , takes place at various stages—those that take place at the level of policy instruments, and those that involve a shift where policymakers reject their own ideas and adopt another. Whereas policymakers are often responsible for the former, the broader social and political forces are the driving factors behind paradigmatic shifts ( Berman, 2013 ).

A robust strand of literature also construes policy change as a product of the confluence of three elements—institutions, interests, and ideas ( Béland, 2009 ; Shearer et al., 2016 ). Institutions refer to the formal and informal rules, norms, beliefs, and precedents that shape the policy response to a crisis ( Mahoney, 2000 ). Interests, on the other hand, reflect the policy choices, material motivations, and agenda, not just of policy actors (elected officials, civil servants), but even of those operating outside the government (societal groups, researchers, policy entrepreneurs) and their desire to influence the policy process to attain their own ends ( Kern, 2011 ; Prechel and Boies, 1998 ). Meanwhile, ideas refer to knowledge or belief about what is (scientific or factual knowledge), what ought to be (values), or a combination of these ( Pomey et al., 2010 ). Ideas can become decisive causal factors in policy change if there are considerable institutional impediments that weaken the capacity of political actors to promote the adoption of a concrete policy alternative ( Béland, 2009 ).

However, institutions, ideas, and interests are not mutually exclusive. Policy change can generally be caused by a shift in one, or their combination, and alter the structure of a policy network. For ideas to be realized, for instance, there have to be advocates. Interests, on the other hand, need to be able to modify behavior to attain the survival of ideas by contending or cooperating with other interests. In the context of the policy process, ideas may reflect ideological considerations or citizens’ values. Ideology and values, in turn, are gauged empirically by looking at how public opinion plays a role in the diffusion or modification of policies. Wlezien (1995) , for instance, conceives a model of public responsiveness in which citizens behave like a thermostat that sends a signal to the government when policy deviates from their preference so that this policy can change accordingly. Supposedly, critical public opinion ceases once policy is in congruence with citizen demand.

COVID-19 response as policy adaptation and experimentation

Existing works on the politics of the COVID-19 response in the Philippines have ubiquitously highlighted policy failure in the backdrop of a populist regime ( Aguilar, 2020 ; Hapal, 2021 ; Teehankee, 2021 ). However, such preoccupation with populism as a one-size-fits-all account not only hampers a more nuanced examination of policy discourse ( De Cleen and Glynos, 2021 ) but ignores the relevance of citizens as stakeholders and policy participants ( Kweit and Kweit, 2004 ). This article digresses from the conventional populist formula and contributes through an empirical inquiry of the relationship between citizen demand and policy response.

Like many in Southeast Asia during the early phase of the pandemic, the Philippines’ response to COVID-19 was fidgety, imperfect, and disproportionate. Dewi et al. (2020) note that public officials with very limited information dealt with the pandemic through a plethora of policy strategies that were not necessarily the most effective. These disproportionate policy reactions are a form of policy overreaction driven by the challenges that elected officials faced while coordinating extant policy strategies and collecting public health information. In search of the most effective response, governments repeatedly undertake a trial-and-error process of agenda setting, formulation, implementation, and evaluation, while exploring multiple policy possibilities. At crucial junctures, policy problems, their solutions, and the political environment converge and pave the way for an intervention that is acceptable to the public. But because resources vary by country, governments also take different approaches in their struggle with the pandemic. Inevitably, they may also be constrained by balancing the need to secure citizens’ economic well-being with managing shocks to the healthcare system.

Studies such as those by Purnomo et al. (2022: 2) characterize the Philippines’ COVID-19 response as underreactive, or one in which there is “a systematic stagnant or inadequate response by government officials to high risks or no response at all.” Interestingly, countries which underreact to the pandemic also exhibit rapid COVID-19 transmission. Policy reaction, however, is not just a function of economic or institutional readiness. Dewi et al.'s (2020) findings imply, for instance, that overall collective opinion and well-being is related to the manner by which policymakers respond to the pandemic.

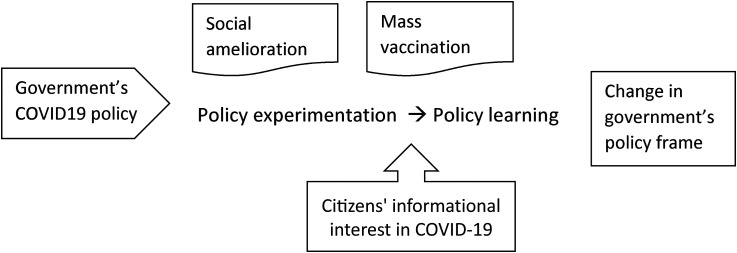

Our theoretical premise construes citizens’ pocketbook assessment of economic uncertainty under COVID-19—operationalized by their search interest on the pandemic—as catalyzing a critical juncture, and applies it in the context of the COVID-19 response in the Philippines ( Figure 1 ). In our view, this juncture is capable of triggering a learning or realization process on the part of policymakers that allows incremental or small changes in policy through problem-solving approaches ( Dunlop and Radaelli, 2013 ; Flink, 2017 ) and is reflected in policy narratives. We follow Moyson et al. (2017) and construe this learning process as having both cognitive and social components in which information and experience are used to inform, substantiate, or legitimize policy beliefs and objectives ( Bennett and Howlett, 1992 ; Dunlop and Radaelli, 2013 ).

Public's search interest and government's shifting policy narrative on COVID-19.

In this framework, stakeholder and citizen engagement feedback are valuable sources of policy learning, especially in the changing governance setting of governments grappling with COVID-19 as a critical juncture. We consider critical juncture as “a situation of extreme challenge and uncertainty” where institutional and social policies and practices have the propensity to result in fundamental change ( Twigg, 2020 ). We contribute by providing empirical support to the notion of crisis as critical juncture and as a causal determinant of policy shifts, using the Philippine government's COVID-19 policy response as a case study.

As is perhaps the case elsewhere, policy response to COVID-19 in the Philippines was relegated to a specialized technical group that operated autonomously and made policy decisions that were often insulated from political factors. Accordingly, policy actions concerning COVID-19 routinely proceeded from a single source and had been, to borrow from the punctuated equilibrium literature, “in a relative state of equilibrium” ( Amri and Drummond, 2020 ). The Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) is the body primarily responsible for all matters concerning emerging infectious diseases, such as swine flu and the novel coronavirus. The IATF-EID was convened in January 2020 but it was neither ad-hoc nor new, having been created through Executive Order 168 issued by former president Benigno Simeon Aquino on May 26, 2014.

Since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the government's response had been highly reactive and focused initially on minimizing the novel coronavirus’ impact on the economy. For instance, three of the four pillars of the Duterte administration's socioeconomic strategy against COVID-19 (see e.g. Department of Finance, n.d.) were all towards providing short-term financial or monetary support to facilitate economic recovery. Building public health resilience as a long-run priority was never on the agenda and state officials reportedly even downplayed the threat of the virus ( Dancel, 2020 ). The IATF provided operational command to the government's pandemic response but a coordination problem mired these efforts. Some local governments had to be more resourceful and took the initiative to secure vaccine doses instead of waiting for the national government to finalize agreements with international vaccine suppliers ( Ranada, 2021 ). The IATF, as a government-led agency, was also criticized for its lack of appropriate pandemic experts (e.g. epidemiologists), its reliance on former military officers for leadership, and for discounting inputs from important stakeholders such as businesses ( Inquirer , 2021 ).

By March 2021, the Philippines had had the world's longest lockdown—a notoriety largely derided in the international press as testament to the government's botched pandemic response ( Madarang, 2021 ). Perhaps the government thought that by limiting people's mobility it would be able to curb the spread of the virus and make a quick rebound. But people had a different appreciation of the pandemic and held different perspectives as to which policies have the most impact. Community lockdowns dislocated people from their livelihoods, creating the very conditions the government wanted to avert. As the lockdown prolonged, citizens became weary of the existing COVID-19 response and started to demand alternatives that would ease economic dislocations during and beyond the pandemic. Community quarantines and restricted mobility soon shifted public discourse on government policy from economic safety nets to the benefits of mass inoculation. On February 28, 2021, the Philippines received its first COVID-19 vaccines—the last among ASEAN countries. The government officially began its vaccine rollout on March 1, 2021, starting with medical frontliners.

Data, variables, and analytical approach

Political texts are known to be vectors of policy positions ( Laver and Garry, 2000 ). They also serve as a rich source of policy narratives which have played a key role in effective COVID-19 responses by creating opportunities for policy learning ( Mintrom and O’Connor, 2020 ).

To gauge the Philippine government's policy position on COVID-19, we compiled a dataset consisting of a corpus of 16,281 press releases on the novel coronavirus posted online by the PNA between January 30, 2020 and April 15, 2021. Since the corpus consists of the government's own press releases, it is not expected to be disinterested or neutral. As many of the press releases are likely propaganda, their selective presentation of government programs may be more towards reinforcing personality politics in the Philippines than anything else. However, as is typical in studies of this type, our interest is precisely to read the government's policy position from a corpus consisting of its own statements. This is consistent with studies that analyze political texts from unilateral sources such as party manifestos ( Eder et al., 2017 ), party elite interviews ( Ecker et al., 2022 ), and public pronouncements or speeches by key political actors such as chief executives ( Kaufman, 2020 ; Panao and Pernia, 2022 ).

The PNA (https:// www.pna.gov.ph ) is a web-based newswire service of the Philippine government, supervised by the News and Information Bureau (NIB) of the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO), and is responsible for disseminating relevant newspaper articles to local and international news agencies. The data coverage begins with January 30 as this was the date of the first reported case of the novel coronavirus in the Philippines ( Edrada et al., 2020 ). However, data-wise, the earliest PNA article on COVID-19 appeared only on February 15, 2021. We then derived topic models using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a semi-supervised probabilistic approach of finding latent or hidden topics in a collection of documents by going through the distribution of co-occurring words or vocabulary ( Blei and Jordan, 2004 ; Blei and Lafferty, 2007 ), and implemented them through the R-based application Quanteda ( Benoit et al., 2018 ).

This procedure produced 10 topics. However, only seven of these exhibited thematic coherence. The topics contained words associated with the following: the economy, vaccination, testing, security, financial aid, hospitalization, and tourism. The procedure allows for the computation of a topic score (a value between 0 and 1) which may be construed broadly as the percentage by which a topic or theme characterizes a particular document. From this, we computed a mean topic score for each news date and constructed a day-to-day series, since COVID-19 updates occur on a daily basis. We operationalize the government's policy shift as the difference between the average daily scores for the economy and vaccination, respectively.

However, politicians and bureaucrats do not have a monopoly of policy formulation. We gauge citizen interest by examining the magnitude and pattern by which Filipinos have queried the COVID-19 pandemic on the internet. The big data platform Google Trends was utilized to construct a series of daily COVID-19-related searches for the Philippines categorized into the following search topics: economy (“economy,” “recession,” “unemployment,” “Philippine economy, “beneficiary,” “social amelioration program”), vaccination (“vaccine,” “COVID-19 vaccine,” “Astrazeneca,” “Pfizer,” “Moderna,” “Sinovac”), symptoms (“COVID-19 sign,” “COVID-19 symptom,” “asymptomatic”), and lockdown (“lockdown,” “community quarantine”). Although the categories are subjective, the search keywords are not arbitrary. Words such as unemployment, recession, and social amelioration, for instance, are all related search terms that trended with economy as a search topic. COVID-19 vaccine brands, particularly AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Moderna, and Sinovac, also figured prominently as popular search topics when people keyed the term “COVID-19 vaccine.” These are the four brands officially administered to the Filipino public as part of the government's inoculation effort at the time of data collection.

In recent years, online political discourse has come to be accepted as an approximation or surrogate of public opinion comparable to social surveys ( Caldarelli et al., 2014 ; Kalampokis et al., 2013 ; Kwak and Cho, 2018 ; O’Leary, 2015 ). Aside from Twitter, Google Trends also figures in the literature as a big data alternative for gauging public opinion and for analyzing the way by which consumers seek information ( Jun et al., 2018 ). Kwak and Cho (2018) believe that Google Trends reflects more genuine thoughts because it is not shared by other social media users and is less susceptible to the bandwagon effect and social desirability bias. In practice, Google Trends is also relatively easier to use.

In the politics and policy literature, Google Trends has figured as a measure of issue salience ( Dube and Kaplan, 2012 ; Graefe et al., 2014 ; Reilly et al., 2012 ) as well as public attention to issues ( Ciuk and Yost, 2016 ; Weeks and Southwell, 2010 ). It has been used to study energy policy ( Oltra, 2011 ), public interest on space exploration ( Whitman Cobb, 2015 ), public interest on biodiversity ( Troumbis, 2017 ), the impact of local health restriction on abortion ( Reis and Brownstein, 2010 ), and the impact of global public health on health-seeking behavior ( Havelka et al., 2020 ), and even to predict presidential elections ( Prado-Román et al., 2021 ) and construct an index of racial prejudice ( Stephens-Davidowitz, 2014 ).

We clarify that resort to search trends is our attempt at approximating public opinion. By search trend, we refer specifically to search interest—that is, what Filipinos search for in real time as events unfold—and not citizens’ news consumption. A survey conducted in 2021 by Pulse Asia indicates that about six in 10 Filipinos use the internet and also about six in 10 log in more than once a day (Gonzales, 2021a). Admittedly, search interest is a crude measure, considering that the same survey also indicates that television remains the top news source for Filipinos, especially on politics and government. Only 48 percent of Filipinos rely on the internet for news, of which 44 percent say they get their news from Facebook (Gonzales, 2021b). This is a limitation we acknowledge in this article.

We construe the aforementioned COVID-19 search trends as encompassing the Filipino public's concern or interest in COVID-19-related issues. We hypothesize that in the framing of its COVID-19 policy, the government's focus on social amelioration increases as citizens’ interest in economic conditions increases, but only up to a point. As citizen's interest in economic conditions heightens further, the focus on social amelioration diminishes as the government shifts its emphasis on vaccination to convince the public to have themselves inoculated.

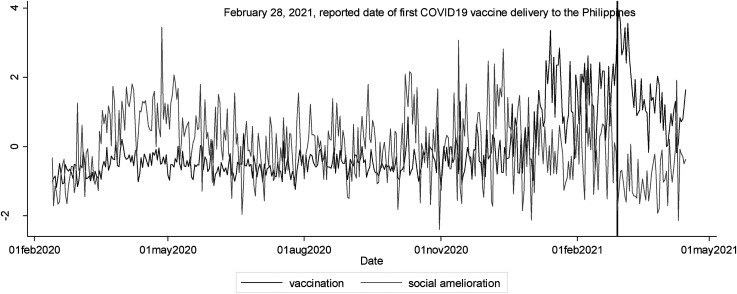

We begin with a descriptive and visual examination of the data and its component variables. A logistic regression entails modeling the probability of the presence or existence of a particular event or class. In this case, our interest is in the probability of COVID-19-related vaccination getting more attention than social amelioration as a thematic focus of government policy narrative. An event is construed operationally as one in which vaccination as a topic model in the press release corpus exceeds social amelioration as a topic share for a given date. The graph in Figure 2 gives an informal comparison between vaccination and social amelioration as topics in the aggregated press releases issued between February 2020 and May 2021. To facilitate visual assessment, the values are normalized for both variables of interest.

COVID-19 vaccination and social amelioration as topic models. Note: Values are normalized to facilitate visual comparison.

As the graph suggests, the government's economic response to COVID-19 has been considerably oriented towards mitigating the social cost of the pandemic. However, the trend appears to dissipate and over time the government's policy position seems to shift towards mass vaccination. Interest in mass vaccination, on the other hand, had a steadily trending increase that became more conspicuous sometime in the middle of January. The vertical line corresponding to February 28, 2021 indicates the date when the Philippines officially received its first delivery of COVID-19 vaccines. The press touted the event as kick-starting the government's mass inoculation campaign ( Tomacruz, 2020 ). The highest observed search interest was on March 1, 2021. Meanwhile, the highest reported search interest on social amelioration was on April 27, 2020. The variable pertaining to the government's shifting policy narratives takes only two values (1 and 0). In the dataset, more than a third (36 percent) of the observations refer to instances in which vaccination received more policy attention than social amelioration. Table 1 gives a descriptive summary of the variables.

Descriptive statistics.

In the models, a day lag is used for all independent variables to ensure causality.

Table 2 summarizes the estimates for three logistic regression models gauging the effect of citizens’ concern about the economy on the government's COVID-19 policy position. Model 1 is an unrestricted model containing both linear and squared specification for query interest on the economy, while controlling for other COVID-19-related search topics, as well as the number of daily confirmed cases and deaths. Model 2 specifies interest in the economy as having only a linear relationship but likewise includes the previously identified control variables. The hypothesis suggests that citizens’ growing concern about the economy would, at some point, cause the government's policy focus to pivot from social amelioration to mass vaccination. It is not enough for this assumption to have a theoretical basis, however; the data must also provide structural support. Hence, following Cohen (2013) , we ran Box-Tidwell ( Box and Tidwell, 1962 ) transformations for the models to check whether our data support a curvilinear conjecture. Box-Tidwell regressions for the first two models did not converge. Meanwhile, the Box-Tidwell transformation for a more parsimonious specification seems to suggest a curvilinear relationship for interest in the economy, interest in vaccines, and new confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Summary of logistic regression estimates.

Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To examine whether the squared terms have explanatory power even with streamlined parameters, we conducted link tests for model adequacy ( Pregibon, 1980 ; Tukey, 1949 ). Similarly, the link tests seem to prefer the parsimonious parameters in Models 3 and 4. Model 3 includes squared terms for the three variables assumed to be curvilinear but vaccine interest in this specification does not appear to have a significant effect. Model 4, which restricts the assumption of a curvilinear relationship to interest in the economy and new confirmed cases, also suggests that the relationship between interest in vaccines and a shifting policy narrative is linear.

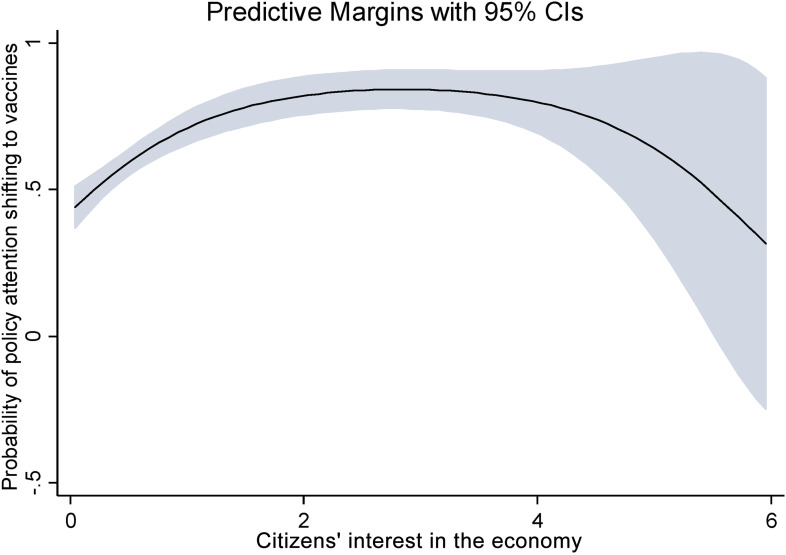

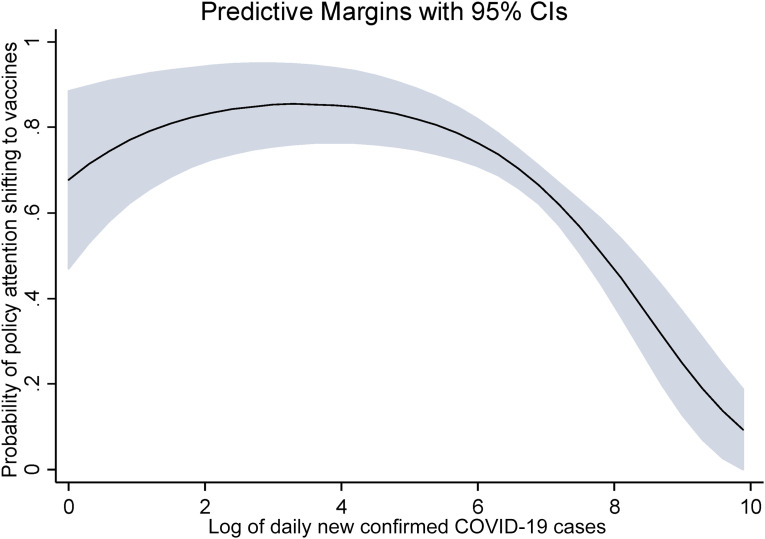

Both Models 3 and 4 support the hypothesis that citizens’ pocketbook assessments of the economy have both short-and long-term effects on the government's policy response. The curvilinear relationship suggests that as Filipinos anxiously inquire about their livelihood and the economy amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the government responds by providing social safety nets as an initial response. But as such interest in their economic condition heightens due to prolonged economic disruptions, the government is constrained to shift its policy focus towards wide-scale inoculation. For a more tangible notion of how much citizens’ pocketbook assessment of the economy shapes government policy, we examine adjusted predicted probabilities at various magnitudes, while all other variables are set at their means. To facilitate interpretation, the graph in Figure 3 illustrates the relationship visually.

Citizen's search interest in the economy and government's policy frame.

Note: The grey areas indicate confidence intervals.

In periods in which citizens’ apprehension about the economy is still manageable, policy attention on social amelioration is also low and government has room to explore other policy options such as mass vaccination in its narrative. As people become more anxious about worsening economic dislocations, however, policy attention to social amelioration also increases in an attempt to pander to citizens’ demand. As economic anxiety heightens further, policy attention shifts back to mass vaccination, possibly as a long-term response. In Model 4, the turning point is when interest in the economy is at 2.8. The mean of the economic interest index is 1.7. About 20 percent of the observations are equal or above the tipping point, suggesting that the curvilinear specification is justified.

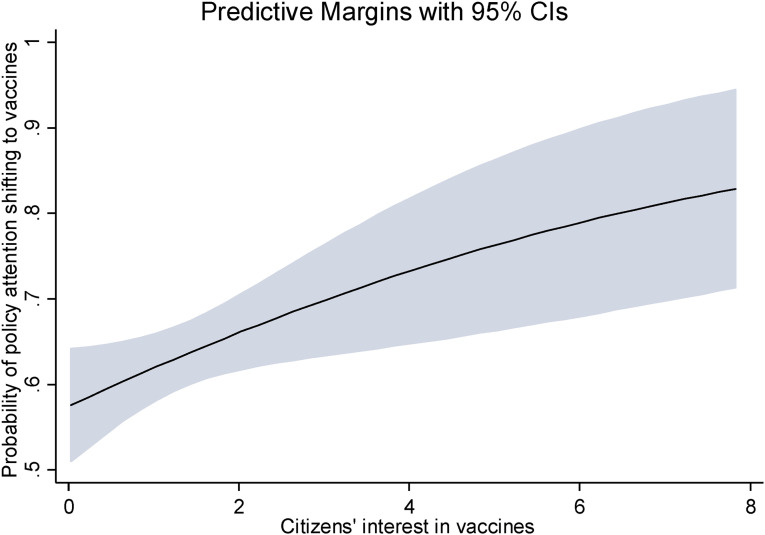

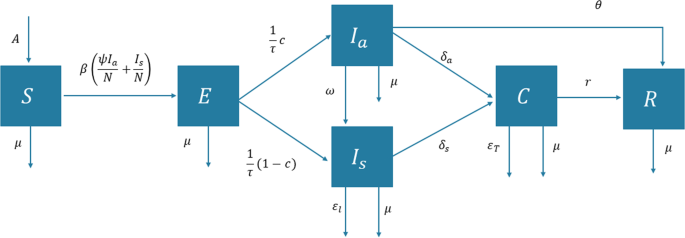

Model 4 also suggests that there is only a linear relationship between citizens’ interest in vaccines and policy attention. The probability of the government highlighting mass inoculation in its policy narrative increases with the public's growing interest in vaccines. Under a linear specification, this relationship is straightforward and statistically very significant. Figure 4 depicts this relationship visually.

Citizens’ search interest in vaccines and government's policy frame.

As with an interest in economic conditions, the number of daily confirmed new COVID-19 cases has a curvilinear relationship with attention to vaccines in the government's policy narrative. Although no specific hypothesis was posited for this variable, the result is intuitive and consistent with the article's overall theoretical conjecture. Based on the findings, the government panders to citizens’ demand for ameliorative socioeconomic interventions as daily COVID-19 cases increase, but only up to a point. Figure 5 shows that as the number of daily infections increases, policy attention shifts to vaccines in the government's policy narrative.

Daily new COVID-19 cases and policy frame.

In this article, we show that the Philippine government's framing of its response to the pandemic has vacillated between easing socioeconomic dislocations through temporary social amelioration and convincing the public to get inoculated. As citizens become interested in the economic implications of the pandemic, the government responds by highlighting social amelioration in its policy narratives. However, as citizens’ search interest increases with mounting economic dislocations, the government is constrained to redirect the focus of its policy narratives towards mass vaccination.

In the media, this approach was heavily criticized for slowing down the rollout of vaccines and aggravating the economic stagnation brought by mobility curbs at the height of the pandemic ( Gonzales, 2021 ). Securing and delivering vaccines to ensure immediate access to the most vulnerable people has long been a recognized public health policy ( Carroll et al., 2015 ; Hasan et al., 2021 ), and the Philippines may have acted a little late in this regard. Some in the Filipino medical community blame delayed procurement for the slow pandemic recovery ( Macaraeg, 2021 ), an indication of mismanagement according to some political coalitions ( Ramos, 2021 ). Studies observed that when the second wave of infection hit the Philippines in 2021, the government was so preoccupied with reallocating resources to COVID-19 that it did not take long for the public health system to become overwhelmed ( Uy et al., 2022 ). By April 2021, rising numbers of cases pushed many facilities to critical capacity, so much so that hospitals turning away both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients had become commonplace ( Morales and Lema, 2021 ).

Arguably, the patchy state of the healthcare system tells a lot about the quality of the government response. It may be contended further that the government's semblance of responsiveness was all part of performance politics in anticipation of the 2022 elections. These are valid claims worthy of further scholarly introspection. Their elaboration, however, is beyond the scope of this article. What seems to be certain is that, like its counterparts elsewhere, the Philippine government was motivated and constrained by whatever capacity and opportunity were available in the creation of its pandemic response ( Capano et al., 2020 ; Rudan, 2021 ). If COVID-19 is straining the public health system of wealthy countries, conditions are worse in developing countries grappling with social protection and health financing ( Shadmi et al., 2020 ). Even before the pandemic, the Philippine healthcare system was already ill-prepared with its poorly funded public hospitals and inadequate social health insurance ( Obermann et al., 2006 ; Querri et al., 2018 ). Current missteps and poor strategy amidst the pandemic only magnified what is already obvious.

The government initially anchored its COVID-19 response on a social amelioration program intended to minimize the economic cost of business suspensions and lockdowns. Operating on the assumption that the pandemic will only be temporary, the government pandered to citizens’ demand for social assistance payments and the physical distribution of cash. But social assistance programming being expensive, inefficient, and susceptible to imperfect targeting ( Gerard et al., 2020 ), public demand for additional economic assistance also became a wake-up call of sorts for the government to seek a long-term public health option. Policy learning without a doubt occurred late but nonetheless this is far from the conventional populist description of seeking easy solutions or spectacularizing the crisis response. This is also consistent with prior accounts of resourced-constrained governments with fragmented political institutions opting for incremental policy changes over comprehensive reforms when faced with a health crisis ( Oliver, 2006 ).

Nevertheless, we do acknowledge methodological limitations whose exploration would no doubt provide a richer understanding of crisis policy framing in the Philippines. Television, for instance, remains the top news source for Filipinos and may provide another dimension to Filipinos’ information-seeking behavior if data can be derived meaningfully. Filipinos’ social media behavior also suggests a promising platform for analyzing the link between public opinion and public policy, subject to parameters that will minimize the noise and bias in generated data ( Olteanu et al., 2019 ).

Our findings have a number of implications. While regimes matter in dissecting pandemic responses, there is a lot to learn from citizens’ emotions and their potential to catalyze desirable policy outcomes. Also, in developing countries with patchy healthcare systems, the difficulty balancing between economic and public health priorities could just as easily be a function of structural inadequacy as it is of administrative inefficiency. Finally, in future pandemic response it may be worthwhile for governments to keep in mind that policy learning is meaningless unless decision makers act with coherence, foresight, and a sense of immediacy.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a grant for research on COVID19 in the Philippines from the Institute of Mathematics, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman.

ORCID iD: Rogelio Alicor L Panao https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9834-1318

Contributor Information

Rogelio Alicor L Panao, University of the Philippines Diliman, Philippines.

Ranjit Singh Rye, University of the Philippines Diliman, Philippines.

- Aguilar FV. (2020) Preparedness, agility, and the Philippine response to the COVID-19 pandemic the early phase in comparative Southeast Asian perspective. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 68(3–4): 373–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- Amri MM, Drummond D. (2020) Punctuating the equilibrium: An application of policy theory to COVID-19. Policy Design and Practice 4(1): 33–43. 10.1080/25741292.2020.1841397. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Béland D. (2009) Ideas, institutions, and policy change. Journal of European Public Policy 16(5): 701–718. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beltran M. (2020) The Philippines’ pandemic response: A tragedy of errors. The Diplomat, 12 May. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/the-philippines-pandemic-response-a-tragedy-of-errors/ (accessed 04 February 2023). [ Google Scholar ]

- Bennett CJ, Howlett M. (1992) The lessons of learning: Reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sciences 25(3): 275–294. [ Google Scholar ]

- Benoit K, Watanabe K, Wang H, et al. (2018) Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software 3(30): 774–778. 10.21105/joss.00774.. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berman S. (2013) Ideational theorizing in the social sciences since “policy paradigms, social learning, and the state”: Ideational theorizing in political science. Governance 26(2): 217–237. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blei DM, Jordan MI. (2004) Variational methods for the Dirichlet process. In: Twenty-first international conference on machine learning – ICML ’04. 10.1145/1015330.1015439. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blei DM, Lafferty JD. (2007) A correlated topic model of science. The Annals of Applied Statistics 1(1): 17–35. 10.1214/07-AOAS114. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Box GEP, Tidwell PW. (1962) Transformation of the independent variables. Technometrics 4(4): 531–550. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brodeur A, Gray D, Islam A, et al. (2021) A literature review of the economics of COVID–19. Journal of Economic Surveys 35(4): 1007–1044. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burstein P. (2003) The impact of public opinion on public policy: A review and an agenda. Political Research Quarterly 56(1): 29–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cairney P, Jones MD. (2016) Kingdon’s multiple streams approach: What is the empirical impact of this universal theory? Kingdon’s multiple streams approach. Policy Studies Journal 44(1): 37–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caldarelli G, Chessa A, Pammolli F, et al. (2014) A multi-level geographical study of Italian political elections from twitter data. PLoS ONE 9(5): e95809. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capano G, Howlett M, Jarvis DSL, et al. (2020) Mobilizing policy (in)capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy and Society 39(3): 285–308. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capoccia G, Kelemen RD. (2007) The study of critical junctures: Theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Politics 59(3): 341–369. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carroll S, Rojas AJG, Glenngård AH, et al. (2015) Vaccination: Short- to long-term benefits from investment. Journal of Market Access & Health Policy 3(1): 27279. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciuk DJ, Yost BA. (2016) The effects of issue salience, elite influence, and policy content on public opinion. Political Communication 33(2): 328–345. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, et al. (2013) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd edn. New York: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203774441. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dancel R. (2020) Coronavirus: Philippines reports first case of local infection, officials downplay fears of community spread. The Strait Times, 6 March. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/philippines-reports-first-local-infection-of-coronavirus-officials-downplay-fears-of (accessed 30 June 2021). [ Google Scholar ]

- De Cleen B, Glynos J. (2021) Beyond populism studies. Journal of Language and Politics 20(1): 178–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Finance (n.d.) The Duterte administration’s 4-pillar socioeconomic strategy against Covid-19. Available at: https://www.dof.gov.ph/the-4-pillar-socioeconomic-strategy-against-covid-19/ (accessed 04 February 2023).

- Dewi A, Nurmandi A, Rochmawati E, et al. (2020) Global policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: Proportionate adaptation and policy experimentation: A study of country policy response variation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Promotion Perspectives 10(4): 359–365. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donnelly P, Hogan J. (2012) Understanding policy change using a critical junctures theory in comparative context: The cases of Ireland and Sweden. Policy Studies Journal 40(2): 324–350. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dube A, Kaplan E. (2012) Occupy Wall Street and the political economy of inequality. The Economists’ Voice 9(3): 1–7. 10.1515/1553-3832.1899. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunlop CA, Radaelli CM. (2013) Systematising policy learning: From monolith to dimensions. Political Studies 61(3): 599–619. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ecker A, Jenny M, Müller WC, et al. (2022) How and why party position estimates from manifestos, expert, and party elite surveys diverge: A comparative analysis of the ‘left–right’ and the ‘European integration’ dimensions. Party Politics 28(3): 528–540. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eder N, Jenny M, Müller WC. (2017) Manifesto functions: How party candidates view and use their party’s central policy document. Electoral Studies 45: 75–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edrada EM, Lopez EB, Villarama JB, et al. (2020) First COVID-19 infections in the Philippines: A case report. Tropical Medicine and Health 48(1): 21–28. 10.1186/s41182-020-00203-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]