Writers on Writing: 20 Best Essays on Writing from Famous Authors

By Jason Boyd

Updated August 7, 2021

What better way to learn about writing novels, short stories, or any creative work than from essays on writing from legendary writers.

Whether you’re gearing up for your first run at a novel ( NaNoWriMo approaches) or looking for a tune-up before embarking on your umpteenth creative writing project, you need inspiration.

May as well be inspired by the best. And maybe be taught a thing or two along the way!

Books vs Essays on Writing Fiction

Why did we choose essays?

Firstly, we certainly may write an article in the future on books from writers on writing. So, there’s no harm in leaving that topic to the side.

But chiefly, our concern is wanting to lend a hand that can be used right now. Right away. With speed.

An essay can be read in a sitting or on the way from one thing to the next, but a book is a time investment. We wanted the delivery to be quick.

Not only do we live in a fast paced world, it can be a bit of a waste to read an entire book about writing a book. Most writers would likely say you’re better off reading a great novel. Or writing one.

Not that we discourage books or any written work on the subject of writing. We don’t . But we wanted a solution for the busy working class person looking to learn the craft.

Someone with limited time but boundless spirit.

This is for you.

20 Essays from Famous Writers on Writing Fiction

We chose to not repeat authors, although quite a few writers that made this list penned multiple essays worth reading.

We picked our favorite and tried to mention the other noteworthy reads somewhere in their entry.

So, without further ado, let’s take a look at our selection of essays from writers on writing.

20) Quick Cuts: The Novel Follows Film Into a World of Fewer Words by E.L. Doctorow

E.L. Doctorow , noted essayist and author of Ragtime , is no stranger to Hollywood.

With many adaptations under his belt, including Ragtime and Billy Bathgate , Doctorow is well suited to discuss the differences between film and literature.

This essay, published in The New York Times , opines on the changes in literature since the advent of the motion picture.

Notable differences include quickening of pace, shortening of exposition, and more personal narratives.

It’s an especially fine read for anyone looking to find distinction between the disciplines of screenwriting and prose.

Brief Excerpt, “Quick Cuts: The Novel Follows Film Into a World of Fewer Words”

“Beyond that, the rise of film art is coincident with the tendency of novelists to conceive of compositions less symphonic and more solo voiced, intimate personalist work expressive of the operating consciousness. A case could be made that the novel’s steady retreat from realism is as much a result of film’s expansive record of the way the world looks as it is of the increasing sophistications of literature itself.” E.L. Doctorow

19) The Ecstasy of Influence by Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem , author of Motherless Brooklyn , is known for his blending of multiple genres.

It only makes sense that he should write so eloquently on the power and responsibility of using influences in original work.

This essay, published originally in Harper’s Magazine , explores the challenges artists face when composing something that pays homage or outright borrows from older works.

Where does one draw the line between plagiarism and inspiration?

Brief Excerpt, “The Ecstasy of Influence”

“Blues and jazz musicians have long been enabled by a kind of ‘open source’ culture, in which pre-existing melodic fragments and larger musical frameworks are freely reworked. Technology has only multiplied the possibilities; musicians have gained the power to duplicate sounds literally rather than simply approximate them through allusion. In Seventies Jamaica, King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry deconstructed recorded music, using astonishingly primitive pre-digital hardware, creating what they called ‘versions.’ The recombinant nature of their means of production quickly spread to DJs in New York and London. Today an endless, gloriously impure, and fundamentally social process generates countless hours of music.” Jonathan Lethem

18) Tradition and the Individual Talent by T.S. Eliot

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet T.S. Eliot , writer of The Waste Land and Four Quartets , is as known for his literary criticism and influence as an editor than for his original work.

Thus, it makes sense to include his essay on writing in a vacuum, or rather, the impossibility of such a feat. The literary equivalent of Sir Isaac Newton ‘s phrase “ standing upon the shoulders of giants ,” Eliot’s essay actually caused quite a stir at the time.

Much like everything in the life of T.S. Eliot.

This essay, hosted now by the Poetry Foundation and originally collected in The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism , nearly creates an ouroboros effect.

A “writers on writing” essay from a writer talking about writers writing on the heels of other writers.

Sorry, we couldn’t resist.

Brief Excerpt, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

“No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead. I mean this as a principle of aesthetic, not merely historical, criticism. The necessity that he shall conform, that he shall cohere, is not onesided; what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them.” T.S. Eliot

17) On Style by Susan Sontag

Legendary essayist and activist Susan Sontag , author of In America , exudes a confident personal style.

Sontag is a bit of a Renaissance woman: professor of philosophy, journalist, novelist, playwright, photographer, and much more. To boot, she did this during divisive times, starting in the early 1960s.

It makes sense that we should pay attention to her thoughts on style, especially as she argues for its close juxtaposition to artistic norms.

In “ On Style ,” published in Against Interpretation and Other Essays , Sontag attempts to differentiate style from content.

Perhaps too academic for some beginners, this essay nonetheless helps to shake up preconceptions on the purpose of style in modern writing.

Brief Excerpt, “On Style”

“This means that the notion of style, generically considered, has a specific, historical meaning. It is not only that styles belong to a time and a place; and that our perception of the style of a given work of art is always charged with an awareness of the work’s historicity, its place in a chronology. Further: the visibility of styles is itself a product of historical consciousness. Were it not for departures from, or experimentation with, previous artistic norms which are known to us, we could never recognize the profile of a new style.” Susan Sontag

16) Reflections on Writing by Henry Miller

Author of the infamously banned Tropic of Cancer , Henry Miller blurs the line between autobiography and fiction.

“Miller’s revolution, though, was not a political one,” writes Ralph B. Sipper in the Los Angeles Times’ Miller’s Tale: Henry Hits 100 . “It was the wedding of his life and his art. Actual and imagined experiences became indistinguishable from each other.”

This aspect of the legend’s style lends itself well to Henry Miller’s overarching essay, a true reflection , about a life spent writing.

Brief Excerpt, “Reflections on Writing”

“I believe that one has to pass beyond the sphere and influence of art. Art is only a means to life, to the life more abundant. It is not in itself the life more abundant. It merely points the way, something which is overlooked not only by the public, but very often by the artist himself. In becoming an end it defeats itself. Most artists are defeating life by their very attempt to grapple with it. They have split the egg in two. All art, I firmly believe, will one day disappear. But the artist will remain, and life itself will become not ‘an art,’ but art, i.e., will definitely and for all time usurp the field. In any true sense we are certainly not yet alive.” Henry Miller

15) Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale by Kate Bernheimer

Writer, editor, and critic Kate Bernheimer knows a thing or two about fairy tales.

She’s the founder and editor of the journal Fairy Tale Review , editor of numerous collections on the subject, and an author of fairy tales herself.

So, when Kate Bernheimer talks about fairy tales, you listen. Her essay “ Fairy Tale is Form, Form is Fairy Tale ” explores the underlying structure of fairy tales and its prevalence in much more than old Brothers Grimm stories.

Brief Excerpt, “Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale”

“Perhaps if we recognize the pleasure in form that can be derived from fairy tales, we might be able to move beyond a discussion of who has more of a claim to the ‘realistic’ or the classical in contemporary letters. An increased appreciation of the techniques in fairy tales not only forges a mutual appreciation between writers from so-called mainstream and avant-garde traditions but also, I would argue, connects all of us in the act of living.” Kate Bernheimer

14) Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks by Joy Williams

Author of State of Grace and Pulitzer-prize finalist The Quick and the Dead , novelist, essayist, and short story writer Joy Williams could certainly be considered a writer’s writer.

It makes her especially suited to answer the age old question: why do writers write?

In her essay meditating upon the impetus to write, “ Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks ,” collected first in the anthology Why I Write: Thoughts on the Craft of Fiction , Williams offers several perspectives.

While there are no clear, definitive answers, burgeoning writers may find solace in the seemingly ubiquitous search for meaning.

Brief Excerpt, “Uncanny the Singing That Comes from Certain Husks” by Joy Williams

“The writer doesn’t trust his enemies, of course, who are wrong about his writing, but he doesn’t trust his friends, either, who he hopes are right. The writer trusts nothing he writes—it should be too reckless and alive for that, it should be beautiful and menacing and slightly out of his control. It should want to live itself somehow. The writer dies—he can die before he dies, it happens all the time, he dies as a writer—but the work wants to live.” Joy Williams

13) The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination by J.K. Rowling

You might say J.K. Rowling knows a thing or two about imagination.

What some casual readers–or even fans–of the Harry Potter author might not know is that Rowling faced poverty and abject failure before finding publishing success.

This combination made for the perfect 2008 commencement speech at Harvard University . Although not an essay at first, the speech became a smash hit, garnering the most views of all Harvard commencement addresses .

And, appropriately so, it was later printed as an essay/e-book titled Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and the Importance of Imagination .

Sure to inspire, and possibly soothe or reassure, the speech and resulting transcription should be read by any aspiring writer.

Brief Excerpt, “The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination”

“So why do I talk about the benefits of failure? Simply because failure meant a stripping away of the inessential. I stopped pretending to myself that I was anything other than what I was, and began to direct all my energy into finishing the only work that mattered to me. Had I really succeeded at anything else, I might never have found the determination to succeed in the one arena I believed I truly belonged. I was set free, because my greatest fear had been realised, and I was still alive, and I still had a daughter whom I adored, and I had an old typewriter and a big idea. And so rock bottom became the solid foundation on which I rebuilt my life.” J.K. Rowling

12) Write Till You Drop by Annie Dillard

Poet, essayist, memoirist, novelist, and critic Annie Dillard has a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction to her name as well as finalist honors for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction .

Add to this a bevy of published work, “ Write Till You Drop ” is certainly a motto Annie Dillard lives by.

In her essay, the author of Pilgim at Tinker Creek offers up directives of great relevance for every writer. That’s because the essay’s crux, made plain in the title, is an urging to write.

Yet, the nuance of the advice is what makes this essay especially motivating and highly recommended for any writing aspirant.

Brief Excerpt, “Write Till You Drop”

“Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying person that would not enrage by its triviality?” Annie Dillard

11) Why I Write by Joan Didion

National Book Award for Nonfiction winner and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Biography/Autobiography Joan Didion is a legend.

The author of The Year of Magical Thinking and Slouching Towards Bethlehem , Didion has been described as belonging to the school of New Journalism, which places an emphasis on narrative storytelling and literary techniques in order to communicate its facts.

As such an accomplished and versatile writer, Didion makes a singular subject for the age-old question of why do writers write .

Just like any essay on the subject, Joan Didion’s take is irreplaceably useful for writers. If for no other reason than it frames the writing pursuit as a shared experience resplendent in multiple shades and colors.

The effect being that of a warm and communal embrace.

Brief Excerpt, “Why I Write”

“When I talk about pictures in my mind I am talking, quite specifically, about images that shimmer around the edges. There used to be an illustration in every elementary psychology book showing a cat drawn by a patient in varying stages of schizophrenia. This cat had a shimmer around it. You could see the molecular structure breaking down at the very edges of the cat: the cat became the background and the background the cat, everything interacting, exchanging ions. People on hallucinogens describe the same perception of objects. I’m not a schizophrenic, nor do I take hallucinogens, but certain images do shimmer for me.” Joan Didion

10) That Crafty Feeling by Zadie Smith

Author Zadie Smith bears nearly too many awards to count.

Beginning with White Teeth , her debut novel that took the critical world by storm, Zadie Smith established herself as one of the most noteworthy writers of the modern generation.

How appropriate then, that she spoke to the craft of writing in “ That Crafty Feeling ,” her lecture for students of the Columbia University writing program in March 2008. Smith later collected the speech in essay form in her book Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays .

In her essay, Smith explores many aspects of the writing process, making it a must-read for the sheer fact of learning the variances writers take to arrive at the written word.

Brief Excerpt, “That Crafty Feeling”

“Some writers won’t read a word of any novel while they’re writing their own. Not one word. They don’t even want to see the cover of a novel. As they write, the world of fiction dies: no one has ever written, no one is writing, no one will ever write again. Try to recommend a good novel to a writer of this type while he’s writing and he’ll give you a look like you just stabbed him in the heart with a kitchen knife. It’s a matter of temperament. Some writers are the kind of solo violinists who need complete silence to tune their instruments. Others want to hear every member of the orchestra—they’ll take a cue from a clarinet, from an oboe, even. I am one of those. My writing desk is covered in open novels.” Zadie Smith

9) The Poetic Principle by Edgar Allan Poe

Legendary American poet, critic, editor, and author Edgar Allan Poe knows how to move you.

In “ The Poetic Principle ,” the author of The Raven and The Fall of the House of Usher breaks down exactly how he achieves this feat.

The essay is a must-read for writers not because one should necessarily follow Edgar Allan Poe’s prescription as a kind of formula.

Instead, it should serve as an example that artistic work doesn’t have to be of a purely ecstatic origin.

Writing can be a calculated affair, in part, aimed toward achieving a desired effect.

Brief Excerpt, “The Poetic Principle”

“Thus, although in a very cursory and imperfect manner, I have endeavored to convey to you my conception of the Poetic Principle. It has been my purpose to suggest that, while this Principle itself is , strictly and simply, the Human Aspiration for Supernal Beauty , the manifestation of the Principle is always found in an elevating excitement of the Soul — quite independent of that passion which is the intoxication of the Heart — or of that Truth which is the satisfaction of the Reason.” Edgar Allan Poe

8) Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses by Mark Twain

One might call Mark Twain something of an authority on the craft of writing.

American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name of Mark Twain , earned the honorific of “father of American literature” by William Faulkner himself.

This all contributes to the fact that no one has ever been as thoroughly dragged through the mud and put on a mocking display as Fenimore Cooper.

The deed was done by Mark Twain’s own hand in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn author’s critical essay “ Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses .”

In what amounts to a public tar and feathering, Twain deconstructs Cooper’s writing down to the level of individual word choice.

The essay illustrates many do’s via its adamant don’ts. Not to mention the tiny bit of schadenfreude contained in Cooper’s literary trial.

Brief Excerpt, “Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses”

“Cooper’s word-sense was singularly dull. When a person has a poor ear for music he will flat and sharp right along without knowing it. He keeps near the tune, but is not the tune. When a person has a poor ear for words, the result is a literary flatting and sharping; you perceive what he is intending to say, but you also perceive that he does not say it. This is Cooper. He was not a word-musician. His ear was satisfied with the approximate words. I will furnish some circumstantial evidence in support of this charge.” Mark Twain

7) Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes by Stephen King

Whether you’re a fan or not, there are two undeniable facts about Stephen King . He can write like a whirlwind, and he’s successful at it.

Stephen King has penned more than 60 books, including The Stand and The Dark Tower series, and created his very own multiverse . Among other accolades, he’s received the National Medal of Arts from the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, and the National Book Foundation awarded him the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.

Oh, and his net worth is estimated to reside somewhere around $400 million . Plus, he’s sold more than 350 million copies of his books worldwide. A success, we’d say, even if some critics dislike him .

In addition to writing one of the most-sought books on the writing life and process, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft , he’s written numerous essays. In the field of writers on writing, he’s nearly overqualified.

Seems he’s well qualified for the essay “ Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes ,” which out of all the essays on our list wins the prize for most enticing title.

As fans of Stephen King, we recommend you gobble up anything he has to say on the profession. But regardless, like the title says, it’s only 10 minutes long.

Brief Excerpt, “Everything You Need to Know About Writing Successfully – in Ten Minutes”

“You want to write a story? Fine. Put away your dictionary, your encyclopedias, your World Almanac, and your thesaurus. Better yet, throw your thesaurus into the wastebasket. The only things creepier than a thesaurus are those little paperbacks college students too lazy to read the assigned novels buy around exam time. Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word. There are no exceptions to this rule.” Stephen King

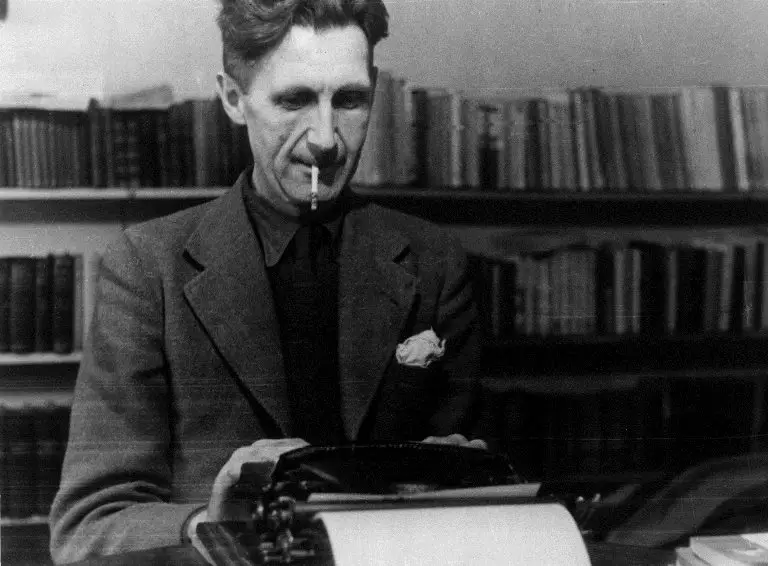

6) Why I Write by George Orwell

Legendary author Eric Arthur Blair , better known by his pen name George Orwell , stands firmly in the great pantheon of 20th century writers.

Author of 1984 and Animal Farm , one might think Orwell’s reason for writing is solely to correct societal wrongs or fight injustices.

First printed in Gangrel (Summer 1946) and later collected in Such, Such Were the Joys , Orwell’s essay “ Why I Write ” details his motivations to write.

Written at first as a response to an editor’s query, the essay serves as both a personal one and an objective observation of the impetus to create.

“I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious — i.e. seriously intended — writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages.” George Orwell

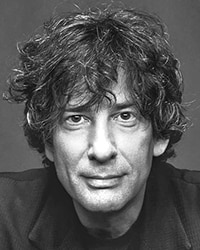

5) Where Do You Get Your Ideas? by Neil Gaiman

When one of today’s greatest originators of fresh concepts tells you that ideas are just one “small component” of writing, you listen.

Neil Gaiman , author of American Gods , The Sandman , Stardust , Coraline , and more, holds a mountain of awards. Among them, the Hugo, Nebula, and Bram Stoker awards. Not to mention a Newbery and Carnegie medal.

And Book of the Year in the British National Book Awards for The Ocean at the End of the Lane .

Written on his own blog, Neil Gaiman’s essay on where he gets his ideas answers the age-old, and somewhat frustrating, question that every writer inevitably gets.

There are no glib answers (okay, maybe a few). He shares his process with sincerity, and packages it partly in a little story, because that’s just what good writers do.

Brief Excerpt, “Where Do You Get Your Ideas?”

“The Ideas aren’t the hard bit. They’re a small component of the whole. Creating believable people who do more or less what you tell them to is much harder. And hardest by far is the process of simply sitting down and putting one word after another to construct whatever it is you’re trying to build: making it interesting, making it new.” Neil Gaiman

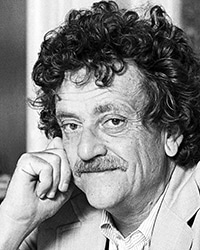

4) Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists by Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

If ever there was a writer’s writer, it’s Kurt Vonnegut Jr. When he gives advice, you listen.

The legendary literary and science fiction author, writer of Slaughterhouse-Five , Vonnegut taught at the esteemed University of Iowa’s writer’s workshop in addition to The City College of New York and Harvard University.

It was in defense of creative writing programs and teachers everywhere that he wrote his essay, “ Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists .”

Not to disparage the school of hard knocks. Quite the opposite.

Kurt Vonnegut instead shows another way of looking at creative writing instructors.

As an extension of a writer’s best friend–a good editor.

Brief Excerpt, “Despite Tough Guys, Life Is Not the Only School for Real Novelists”

“Much is known about how to tell a story, rules for sociability, for how to be a friend to a reader so the reader won’t stop reading, how to be a good date on a blind date with a total stranger.” Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

3) Thoughts on Writing by Elizabeth Gilbert

Elizabeth Gilbert knows writing.

Author of numerous works and amazing TED Talks presenter, Gilbert is everything a writer could want to be.

She writes fiction, non-fiction, books about writing, globe trots while freelancing for magazines, and is a journalist. As of late, she’s transformed into a teacher of sorts, sharing her knowledge far and wide, and one of the leaders in the topic of writers on writing.

Her published material includes Pilgrims (Pushcart Prize winner and finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award), Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia (199 weeks on The New York Times Bestseller List and turned into a movie starring Julia Roberts ), and Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (where she shares the wealth).

To say her essay, “ Thoughts on Writing ,” published on her own blog, is worth the time of any aspiring writer–of any form, medium, or genre–is a drastic understatement.

Brief Excerpt, “Thoughts on Writing”

“As for discipline – it’s important, but sort of over-rated. The more important virtue for a writer, I believe, is self-forgiveness. Because your writing will always disappoint you. Your laziness will always disappoint you.” Elizabeth Gilbert

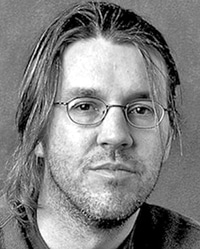

2) The Nature of the Fun by David Foster Wallace

A literary giant in the making cut short by suicidal depression, David Foster Wallace is counted among many of today’s brilliant creative minds.

Author of Infinite Jest , a novel that every intelligentsia claims to have read, although few have managed to conquer its substantial length, Wallace talked extensively about the subject of craft. As a teacher and pundit, he’s let his thoughts be known.

And for writers on writing, he’s often considered a preeminent expert on the topic.

However, “ The Nature of the Fun ” answers that basic question posed to nearly every writer throughout history–why do you write?

For Wallace, the answer is in surprisingly stark contrast to everything else in the tragic writer’s life.

Brief Excerpt, “The Nature of the Fun”

“In the beginning, when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor’s about fun. You don’t expect anybody else to read it. You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off. To enable your own fantasies and deviant logics and to escape or transform parts of yourself you don’t like. And it works – and it’s terrific fun. Then, if you have good luck and people seem to like what you do, and you actually start to get paid for it, and get to see your stuff professionally typeset and bound and blurbed and reviewed and even (once) being read on the a.m. subway by a pretty girl you don’t even know it seems to make it even more fun.” David Foster Wallace

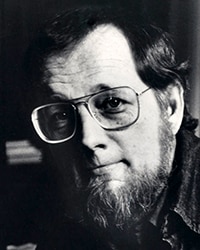

1) Not Knowing by Donald Barthelme

Donald Barthelme is almost certainly not a name you know.

Although there are exceptions, even the most devout of readers overlook the absurdist and surrealist stylings of the postmodern short story writer and teacher.

Funny, considering such eye catching titles as Sixty Stories and Forty Stories .

However, Barthelme was a regular on the pages of The New Yorker , as well as other literary magazines of his time. He even founded one– Fiction .

But don’t fret that you don’t know him. As Barthelme indicates in “ Not Knowing ,” his essay on the creative process, lack of knowledge can lead to invention.

That’s just one reason we recommend this for your reading list, which includes our sincere hope that you also pick up some of Barthelme’s fiction.

Brief Excerpt, “Not Knowing”

“The not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention.” Donald Barthelme

Writers on writing and essays on writing are almost a sub-genre in itself.

For writers out there, be careful that you don’t get sucked into the habit of consuming one diatribe after another, hoping to find eternal wisdom, without actually writing yourself.

It can be alluring, to soak in the soup of published authors, to feel like you’re holding conversations with the greatest minds. Afterall, for some aspiring writers, it’s the end goal of getting published. However, one must start with the actual writing itself, so don’t dawdle too long.

Of course, we hope that these relatively short essays won’t keep you for long. And they’re just meaty enough to be satiating.

Now, get to writing! (including dropping into the comments to share your own writing advice)

Jason Boyd is a science fiction author, geek enthusiast, and former cubicle owner. When not working on his MA in Creative Writing, he's trying to figure out how magnets work.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

40 Best Essays of All Time (Including Links & Writing Tips)

I wanted to improve my writing skills. I thought that reading the forty best essays of all time would bring me closer to my goal.

I had little money (buying forty collections of essays was out of the question) so I’ve found them online instead. I’ve hacked through piles of them, and finally, I’ve found the great ones. Now I want to share the whole list with you (with the addition of my notes about writing). Each item on the list has a direct link to the essay, so please click away and indulge yourself. Also, next to each essay, there’s an image of the book that contains the original work.

About this essay list:

Reading essays is like indulging in candy; once you start, it’s hard to stop. I sought out essays that were not only well-crafted but also impactful. These pieces genuinely shifted my perspective. Whether you’re diving in for enjoyment or to hone your writing, these essays promise to leave an imprint. It’s fascinating how an essay can resonate with you, and even if details fade, its essence remains. I haven’t ranked them in any way; they’re all stellar. Skim through, explore the summaries, and pick up some writing tips along the way. For more essay gems, consider “Best American Essays” by Joyce Carol Oates or “101 Essays That Will Change The Way You Think” curated by Brianna Wiest.

40 Best Essays of All Time (With Links And Writing Tips)

1. david sedaris – laugh, kookaburra.

A great family drama takes place against the backdrop of the Australian wilderness. And the Kookaburra laughs… This is one of the top essays of the lot. It’s a great mixture of family reminiscences, travel writing, and advice on what’s most important in life. You’ll also learn an awful lot about the curious culture of the Aussies.

Writing tips from the essay:

- Use analogies (you can make it funny or dramatic to achieve a better effect): “Don’t be afraid,” the waiter said, and he talked to the kookaburra in a soothing, respectful voice, the way you might to a child with a switchblade in his hand”.

- You can touch a few cognate stories in one piece of writing . Reveal the layers gradually. Intertwine them and arrange for a grand finale where everything is finally clear.

- Be on the side of the reader. Become their friend and tell the story naturally, like around the dinner table.

- Use short, punchy sentences. Tell only as much as is required to make your point vivid.

- Conjure sentences that create actual feelings: “I had on a sweater and a jacket, but they weren’t quite enough, and I shivered as we walked toward the body, and saw that it was a . . . what, exactly?”

- You may ask a few tough questions in a row to provoke interest and let the reader think.

2. Charles D’Ambrosio – Documents

Do you think your life punches you in the face all too often? After reading this essay, you will change your mind. Reading about loss and hardships often makes us sad at first, but then enables us to feel grateful for our lives . D’Ambrosio shares his documents (poems, letters) that had a major impact on his life, and brilliantly shows how not to let go of the past.

- The most powerful stories are about your family and the childhood moments that shaped your life.

- You don’t need to build up tension and pussyfoot around the crux of the matter. Instead, surprise the reader by telling it like it is: “The poem was an allegory about his desire to leave our family.” Or: “My father had three sons. I’m the eldest; Danny, the youngest, killed himself sixteen years ago”.

- You can use real documents and quotes from your family and friends. It makes it so much more personal and relatable.

- Don’t cringe before the long sentence if you know it’s a strong one.

- At the end of the essay, you may come back to the first theme to close the circuit.

- Using slightly poetic language is acceptable, as long as it improves the story.

3. E. B. White – Once more to the lake

What does it mean to be a father? Can you see your younger self, reflected in your child? This beautiful essay tells the story of the author, his son, and their traditional stay at a placid lake hidden within the forests of Maine. This place of nature is filled with sunshine and childhood memories. It also provides for one of the greatest meditations on nature and the passing of time.

- Use sophisticated language, but not at the expense of readability.

- Use vivid language to trigger the mirror neurons in the reader’s brain: “I took along my son, who had never had any fresh water up his nose and who had seen lily pads only from train windows”.

- It’s important to mention universal feelings that are rarely talked about (it helps to create a bond between two minds): “You remember one thing, and that suddenly reminds you of another thing. I guess I remembered clearest of all the early mornings when the lake was cool and motionless”.

- Animate the inanimate: “this constant and trustworthy body of water”.

- Mentioning tales of yore is a good way to add some mystery and timelessness to your piece.

- Using double, or even triple “and” in one sentence is fine. It can make the sentence sing.

4. Zadie Smith – Fail Better

Aspiring writers feel tremendous pressure to perform. The daily quota of words often turns out to be nothing more than gibberish. What then? Also, should the writer please the reader or should she be fully independent? What does it mean to be a writer, anyway? This essay is an attempt to answer these questions, but its contents are not only meant for scribblers. Within it, you’ll find some great notes about literary criticism, how we treat art , and the responsibility of the reader.

- A perfect novel ? There’s no such thing.

- The novel always reflects the inner world of the writer. That’s why we’re fascinated with writers.

- Writing is not simply about craftsmanship, but about taking your reader to the unknown lands. In the words of Christopher Hitchens: “Your ideal authors ought to pull you from the foundering of your previous existence, not smilingly guide you into a friendly and peaceable harbor.”

- Style comes from your unique personality and the perception of the world. It takes time to develop it.

- Never try to tell it all. “All” can never be put into language. Take a part of it and tell it the best you can.

- Avoid being cliché. Try to infuse new life into your writing .

- Writing is about your way of being. It’s your game. Paradoxically, if you try to please everyone, your writing will become less appealing. You’ll lose the interest of the readers. This rule doesn’t apply in the business world where you have to write for a specific person (a target audience).

- As a reader, you have responsibilities too. According to the critics, every thirty years, there’s just a handful of great novels. Maybe it’s true. But there’s also an element of personal connection between the reader and the writer. That’s why for one person a novel is a marvel, while for the other, nothing special at all. That’s why you have to search and find the author who will touch you.

5. Virginia Woolf – Death of the Moth

Amid an ordinary day, sitting in a room of her own, Virginia Woolf tells about the epic struggle for survival and the evanescence of life. This short essay is truly powerful. In the beginning, the atmosphere is happy. Life is in full force. And then, suddenly, it fades away. This sense of melancholy would mark the last years of Woolf’s life.

- The melody of language… A good sentence is like music: “Moths that fly by day are not properly to be called moths; they do not excite that pleasant sense of dark autumn nights and ivy-blossom which the commonest yellow- underwing asleep in the shadow of the curtain never fails to rouse in us”.

- You can show the grandest in the mundane (for example, the moth at your window and the drama of life and death).

- Using simple comparisons makes the style more lucid: “Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure”.

6. Meghan Daum – My Misspent Youth

Many of us, at some point or another, dream about living in New York. Meghan Daum’s take on the subject differs slightly from what you might expect. There’s no glamour, no Broadway shows, and no fancy restaurants. Instead, there’s the sullen reality of living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. You’ll get all the juicy details about credit cards, overdue payments, and scrambling for survival. It’s a word of warning. But it’s also a great story about shattered fantasies of living in a big city. Word on the street is: “You ain’t promised mañana in the rotten manzana.”

- You can paint a picture of your former self. What did that person believe in? What kind of world did he or she live in?

- “The day that turned your life around” is a good theme you may use in a story. Memories of a special day are filled with emotions. Strong emotions often breed strong writing.

- Use cultural references and relevant slang to create a context for your story.

- You can tell all the details of the story, even if in some people’s eyes you’ll look like the dumbest motherfucker that ever lived. It adds to the originality.

- Say it in a new way: “In this mindset, the dollars spent, like the mechanics of a machine no one bothers to understand, become an abstraction, an intangible avenue toward self-expression, a mere vehicle of style”.

- You can mix your personal story with the zeitgeist or the ethos of the time.

7. Roger Ebert – Go Gentle Into That Good Night

Probably the greatest film critic of all time, Roger Ebert, tells us not to rage against the dying of the light. This essay is full of courage, erudition, and humanism. From it, we learn about what it means to be dying (Hitchens’ “Mortality” is another great work on that theme). But there’s so much more. It’s a great celebration of life too. It’s about not giving up, and sticking to your principles until the very end. It brings to mind the famous scene from Dead Poets Society where John Keating (Robin Williams) tells his students: “Carpe, carpe diem, seize the day boys, make your lives extraordinary”.

- Start with a powerful sentence: “I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear.”

- Use quotes to prove your point -”‘Ask someone how they feel about death’, he said, ‘and they’ll tell you everyone’s gonna die’. Ask them, ‘In the next 30 seconds?’ No, no, no, that’s not gonna happen”.

- Admit the basic truths about reality in a childlike way (especially after pondering quantum physics) – “I believe my wristwatch exists, and even when I am unconscious, it is ticking all the same. You have to start somewhere”.

- Let other thinkers prove your point. Use quotes and ideas from your favorite authors and friends.

8. George Orwell – Shooting an Elephant

Even after one reading, you’ll remember this one for years. The story, set in British Burma, is about shooting an elephant (it’s not for the squeamish). It’s also the most powerful denunciation of colonialism ever put into writing. Orwell, apparently a free representative of British rule, feels to be nothing more than a puppet succumbing to the whim of the mob.

- The first sentence is the most important one: “In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people — the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me”.

- You can use just the first paragraph to set the stage for the whole piece of prose.

- Use beautiful language that stirs the imagination: “I remember that it was a cloudy, stuffy morning at the beginning of the rains.” Or: “I watched him beating his bunch of grass against his knees, with that preoccupied grandmotherly air that elephants have.”

- If you’ve ever been to war, you will have a story to tell: “(Never tell me, by the way, that the dead look peaceful. Most of the corpses I have seen looked devilish.)”

- Use simple words, and admit the sad truth only you can perceive: “They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I was momentarily worth watching”.

- Share words of wisdom to add texture to the writing: “I perceived at this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his freedom that he destroys.”

- I highly recommend reading everything written by Orwell, especially if you’re looking for the best essay collections on Amazon or Goodreads.

9. George Orwell – A Hanging

It’s just another day in Burma – time to hang a man. Without much ado, Orwell recounts the grim reality of taking another person’s life. A man is taken from his cage and in a few minutes, he’s going to be hanged. The most horrible thing is the normality of it. It’s a powerful story about human nature. Also, there’s an extraordinary incident with the dog, but I won’t get ahead of myself.

- Create brilliant, yet short descriptions of characters: “He was a Hindu, a puny wisp of a man, with a shaven head and vague liquid eyes. He had a thick, sprouting mustache, absurdly too big for his body, rather like the mustache of a comic man on the films”.

- Understand and share the felt presence of a unique experience: “It is curious, but till that moment I had never realized what it means to destroy a healthy, conscious man”.

- Make your readers hear the sound that will stay with them forever: “And then when the noose was fixed, the prisoner began crying out on his god. It was a high, reiterated cry of “Ram! Ram! Ram! Ram!”

- Make the ending original by refusing the tendency to seek closure or summing it up.

10. Christopher Hitchens – Assassins of The Mind

In one of the greatest essays written in defense of free speech, Christopher Hitchens shares many examples of how modern media kneel to the explicit threats of violence posed by Islamic extremists. He recounts the story of his friend, Salman Rushdie, author of Satanic Verses who, for many years, had to watch over his shoulder because of the fatwa of Ayatollah Khomeini. With his usual wit, Hitchens shares various examples of people who died because of their opinions and of editors who refuse to publish anything related to Islam because of fear (and it was written long before the Charlie Hebdo massacre). After reading the essay, you realize that freedom of expression is one of the most precious things we have and that we have to fight for it. I highly recommend all essay collections penned by Hitchens, especially the ones written for Vanity Fair.

- Assume that the readers will know the cultural references. When they do, their self-esteem goes up – they are a part of an insider group.

- When proving your point, give a variety of real-life examples from eclectic sources. Leave no room for ambiguity or vagueness. Research and overall knowledge are essential here.

- Use italics to emphasize a specific word or phrase (here I use the underlining): “We live now in a climate where every publisher and editor and politician has to weigh in advance the possibility of violent Muslim reprisal. In consequence, several things have not happened.”

- Think about how to make it sound more original: “So there is now a hidden partner in our cultural and academic and publishing and the broadcasting world: a shadowy figure that has, uninvited, drawn up a chair to the table.”

11. Christopher Hitchens – The New Commandments

It’s high time to shatter the tablets and amend the biblical rules of conduct. Watch, as Christopher Hitchens slays one commandment after the other on moral, as well as historical grounds. For example, did you know that there are many versions of the divine law dictated by God to Moses which you can find in the Bible? Aren’t we thus empowered to write our version of a proper moral code? If you approach it with an open mind, this essay may change the way you think about the Bible and religion.

- Take the iconoclastic approach. Have a party on the hallowed soil.

- Use humor to undermine orthodox ideas (it seems to be the best way to deal with an established authority).

- Use sarcasm and irony when appropriate (or not): “Nobody is opposed to a day of rest. The international Communist movement got its start by proclaiming a strike for an eight-hour day on May 1, 1886, against Christian employers who used child labor seven days a week”.

- Defeat God on legal grounds: “Wise lawmakers know that it is a mistake to promulgate legislation that is impossible to obey”.

- Be ruthless in the logic of your argument. Provide evidence.

12. Phillip Lopate – Against Joie de Vivre

While reading this fantastic essay, this quote from Slavoj Žižek kept coming back to me: “I think that the only life of deep satisfaction is a life of eternal struggle, especially struggle with oneself. If you want to remain happy, just remain stupid. Authentic masters are never happy; happiness is a category of slaves”. I can bear the onus of happiness or joie de vivre for some time. But this force enables me to get free and wallow in the sweet feelings of melancholy and nostalgia. By reading this work of Lopate, you’ll enter into the world of an intelligent man who finds most social rituals a drag. It’s worth exploring.

- Go against the grain. Be flamboyant and controversial (if you can handle it).

- Treat the paragraph like a group of thoughts on one theme. Next paragraph, next theme.

- Use references to other artists to set the context and enrich the prose: “These sunny little canvases with their talented innocence, the third-generation spirit of Montmartre, bore testimony to a love of life so unbending as to leave an impression of rigid narrow-mindedness as extreme as any Savonarola. Their rejection of sorrow was total”.

- Capture the emotions in life that are universal, yet remain unspoken.

- Don’t be afraid to share your intimate experiences.

13. Philip Larkin – The Pleasure Principle

This piece comes from the Required Writing collection of personal essays. Larkin argues that reading in verse should be a source of intimate pleasure – not a medley of unintelligible thoughts that only the author can (or can’t?) decipher. It’s a sobering take on modern poetry and a great call to action for all those involved in it. Well worth a read.

- Write about complicated ideas (such as poetry) simply. You can change how people look at things if you express yourself enough.

- Go boldly. The reader wants a bold writer: “We seem to be producing a new kind of bad poetry, not the old kind that tries to move the reader and fails, but one that does not even try”.

- Play with words and sentence length. Create music: “It is time some of you playboys realized, says the judge, that reading a poem is hard work. Fourteen days in stir. Next case”.

- Persuade the reader to take action. Here, direct language is the most effective.

14. Sigmund Freud – Thoughts for the Times on War and Death

This essay reveals Freud’s disillusionment with the whole project of Western civilization. How the peaceful European countries could engage in a war that would eventually cost over 17 million lives? What stirs people to kill each other? Is it their nature, or are they puppets of imperial forces with agendas of their own? From the perspective of time, this work by Freud doesn’t seem to be fully accurate. Even so, it’s well worth your time.

- Commence with long words derived from Latin. Get grandiloquent, make your argument incontrovertible, and leave your audience discombobulated.

- Use unending sentences, so that the reader feels confused, yet impressed.

- Say it well: “In this way, he enjoyed the blue sea and the grey; the beauty of snow-covered mountains and green meadowlands; the magic of northern forests and the splendor of southern vegetation; the mood evoked by landscapes that recall great historical events, and the silence of untouched nature”.

- Human nature is a subject that never gets dry.

15. Zadie Smith – Some Notes on Attunement

“You are privy to a great becoming, but you recognize nothing” – Francis Dolarhyde. This one is about the elusiveness of change occurring within you. For Zadie, it was hard to attune to the vibes of Joni Mitchell – especially her Blue album. But eventually, she grew up to appreciate her genius, and all the other things changed as well. This top essay is all about the relationship between humans, and art. We shouldn’t like art because we’re supposed to. We should like it because it has an instantaneous, emotional effect on us. Although, according to Stansfield (Gary Oldman) in Léon, liking Beethoven is rather mandatory.

- Build an expectation of what’s coming: “The first time I heard her I didn’t hear her at all”.

- Don’t be afraid of repetition if it feels good.

- Psychedelic drugs let you appreciate things you never appreciated.

- Intertwine a personal journey with philosophical musings.

- Show rather than tell: “My friends pitied their eyes. The same look the faithful give you as you hand them back their “literature” and close the door in their faces”.

- Let the poets speak for you: “That time is past, / And all its aching joys are now no

- more, / And all its dizzy raptures”.

- By voicing your anxieties, you can heal the anxieties of the reader. In that way, you say: “I’m just like you. I’m your friend in this struggle”.

- Admit your flaws to make your persona more relatable.

16. Annie Dillard – Total Eclipse

My imagination was always stirred by the scene of the solar eclipse in Pharaoh, by Boleslaw Prus. I wondered about the shock of the disoriented crowd when they saw how their ruler could switch off the light. Getting immersed in this essay by Annie Dillard has a similar effect. It produces amazement and some kind of primeval fear. It’s not only the environment that changes; it’s your mind and the perception of the world. After the eclipse, nothing is going to be the same again.

- Yet again, the power of the first sentence draws you in: “It had been like dying, that sliding down the mountain pass”.

- Don’t miss the extraordinary scene. Then describe it: “Up in the sky, like a crater from some distant cataclysm, was a hollow ring”.

- Use colloquial language. Write as you talk. Short sentences often win.

- Contrast the numinous with the mundane to enthrall the reader.

17. Édouard Levé – When I Look at a Strawberry, I Think of a Tongue

This suicidally beautiful essay will teach you a lot about the appreciation of life and the struggle with mental illness. It’s a collection of personal, apparently unrelated thoughts that show us the rich interior of the author. You look at the real-time thoughts of another person, and then recognize the same patterns within yourself… It sounds like a confession of a person who’s about to take their life, and it’s striking in its originality.

- Use the stream-of-consciousness technique and put random thoughts on paper. Then, polish them: “I have attempted suicide once, I’ve been tempted four times to attempt it”.

- Place the treasure deep within the story: “When I look at a strawberry, I think of a tongue, when I lick one, of a kiss”.

- Don’t worry about what people might think. The more you expose, the more powerful the writing. Readers also take part in the great drama. They experience universal emotions that mostly stay inside. You can translate them into writing.

18. Gloria E. Anzaldúa – How to Tame a Wild Tongue

Anzaldúa, who was born in south Texas, had to struggle to find her true identity. She was American, but her culture was grounded in Mexico. In this way, she and her people were not fully respected in either of the countries. This essay is an account of her journey of becoming the ambassador of the Chicano (Mexican-American) culture. It’s full of anecdotes, interesting references, and different shades of Spanish. It’s a window into a new cultural dimension that you’ve never experienced before.

- If your mother tongue is not English, but you write in English, use some of your unique homeland vocabulary.

- You come from a rich cultural heritage. You can share it with people who never heard about it, and are not even looking for it, but it is of immense value to them when they discover it.

- Never forget about your identity. It is precious. It is a part of who you are. Even if you migrate, try to preserve it. Use it to your best advantage and become the voice of other people in the same situation.

- Tell them what’s really on your mind: “So if you want to hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity – I am my language”.

19. Kurt Vonnegut – Dispatch From A Man Without a Country

In terms of style, this essay is flawless. It’s simple, conversational, humorous, and yet, full of wisdom. And when Vonnegut becomes a teacher and draws an axis of “beginning – end”, and, “good fortune – bad fortune” to explain literature, it becomes outright hilarious. It’s hard to find an author with such a down-to-earth approach. He doesn’t need to get intellectual to prove a point. And the point could be summed up by the quote from Great Expectations – “On the Rampage, Pip, and off the Rampage, Pip – such is Life!”

- Start with a curious question: “Do you know what a twerp is?”

- Surprise your readers with uncanny analogies: “I am from a family of artists. Here I am, making a living in the arts. It has not been a rebellion. It’s as though I had taken over the family Esso station.”

- Use your natural language without too many special effects. In time, the style will crystalize.

- An amusing lesson in writing from Mr. Vonnegut: “Here is a lesson in creative writing. First rule: Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing. All they do is show you’ve been to college”.

- You can put actual images or vignettes between the paragraphs to illustrate something.

20. Mary Ruefle – On Fear

Most psychologists and gurus agree that fear is the greatest enemy of success or any creative activity. It’s programmed into our minds to keep us away from imaginary harm. Mary Ruefle takes on this basic human emotion with flair. She explores fear from so many angles (especially in the world of poetry-writing) that at the end of this personal essay, you will look at it, dissect it, untangle it, and hopefully be able to say “f**k you” the next time your brain is trying to stop you.

- Research your subject thoroughly. Ask people, have interviews, get expert opinions, and gather as much information as possible. Then scavenge through the fields of data, and pull out the golden bits that will let your prose shine.

- Use powerful quotes to add color to your story: “The poet who embarks on the creation of the poem (as I know by experience), begins with the aimless sensation of a hunter about to embark on a night hunt through the remotest of forests. Unaccountable dread stirs in his heart”. – Lorca.

- Writing advice from the essay: “One of the fears a young writer has is not being able to write as well as he or she wants to, the fear of not being able to sound like X or Y, a favorite author. But out of fear, hopefully, is born a young writer’s voice”.

21. Susan Sontag – Against Interpretation

In this highly intellectual essay, Sontag fights for art and its interpretation. It’s a great lesson, especially for critics and interpreters who endlessly chew on works that simply defy interpretation. Why don’t we just leave the art alone? I always hated it when at school they asked me: “What did the author have in mind when he did X or Y?” Iēsous Pantocrator! Hell if I know! I will judge it through my subjective experience!

- Leave the art alone: “Today is such a time, when the project of interpretation is reactionary, stifling. Like the fumes of the automobile and heavy industry which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities”.

- When you have something really important to say, style matters less.

- There’s no use in creating a second meaning or inviting interpretation of our art. Just leave it be and let it speak for itself.

22. Nora Ephron – A Few Words About Breasts

This is a heartwarming, coming-of-age story about a young girl who waits in vain for her breasts to grow. It’s simply a humorous and pleasurable read. The size of breasts is a big deal for women. If you’re a man, you may peek into the mind of a woman and learn many interesting things. If you’re a woman, maybe you’ll be able to relate and at last, be at peace with your bosom.

- Touch an interesting subject and establish a strong connection with the readers (in that case, women with small breasts). Let your personality shine through the written piece. If you are lighthearted, show it.

- Use hyphens to create an impression of real talk: “My house was full of apples and peaches and milk and homemade chocolate chip cookies – which were nice, and good for you, but-not-right-before-dinner-or-you’ll-spoil-your-appetite.”

- Use present tense when you tell a story to add more life to it.

- Share the pronounced, memorable traits of characters: “A previous girlfriend named Solange, who was famous throughout Beverly Hills High School for having no pigment in her right eyebrow, had knitted them for him (angora dice)”.

23. Carl Sagan – Does Truth Matter – Science, Pseudoscience, and Civilization

Carl Sagan was one of the greatest proponents of skepticism, and an author of numerous books, including one of my all-time favorites – The Demon-Haunted World . He was also a renowned physicist and the host of the fantastic Cosmos: A Personal Voyage series, which inspired a whole generation to uncover the mysteries of the cosmos. He was also a dedicated weed smoker – clearly ahead of his time. The essay that you’re about to read is a crystallization of his views about true science, and why you should check the evidence before believing in UFOs or similar sorts of crap.

- Tell people the brutal truth they need to hear. Be the one who spells it out for them.

- Give a multitude of examples to prove your point. Giving hard facts helps to establish trust with the readers and show the veracity of your arguments.

- Recommend a good book that will change your reader’s minds – How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life

24. Paul Graham – How To Do What You Love

How To Do What You Love should be read by every college student and young adult. The Internet is flooded with a large number of articles and videos that are supposed to tell you what to do with your life. Most of them are worthless, but this one is different. It’s sincere, and there’s no hidden agenda behind it. There’s so much we take for granted – what we study, where we work, what we do in our free time… Surely we have another two hundred years to figure it out, right? Life’s too short to be so naïve. Please, read the essay and let it help you gain fulfillment from your work.

- Ask simple, yet thought-provoking questions (especially at the beginning of the paragraph) to engage the reader: “How much are you supposed to like what you do?”

- Let the readers question their basic assumptions: “Prestige is like a powerful magnet that warps even your beliefs about what you enjoy. It causes you to work not on what you like, but what you’d like to like”.

- If you’re writing for a younger audience, you can act as a mentor. It’s beneficial for younger people to read a few words of advice from a person with experience.

25. John Jeremiah Sullivan – Mister Lytle

A young, aspiring writer is about to become a nurse of a fading writer – Mister Lytle (Andrew Nelson Lytle), and there will be trouble. This essay by Sullivan is probably my favorite one from the whole list. The amount of beautiful sentences it contains is just overwhelming. But that’s just a part of its charm. It also takes you to the Old South which has an incredible atmosphere. It’s grim and tawny but you want to stay there for a while.

- Short, distinct sentences are often the most powerful ones: “He had a deathbed, in other words. He didn’t go suddenly”.

- Stay consistent with the mood of the story. When reading Mister Lytle you are immersed in that southern, forsaken, gloomy world, and it’s a pleasure.

- The spectacular language that captures it all: “His French was superb, but his accent in English was best—that extinct mid-Southern, land-grant pioneer speech, with its tinges of the abandoned Celtic urban Northeast (“boned” for burned) and its raw gentility”.

- This essay is just too good. You have to read it.

26. Joan Didion – On Self Respect

Normally, with that title, you would expect some straightforward advice about how to improve your character and get on with your goddamn life – but not from Joan Didion. From the very beginning, you can feel the depth of her thinking, and the unmistakable style of a true woman who’s been hurt. You can learn more from this essay than from whole books about self-improvement . It reminds me of the scene from True Detective, where Frank Semyon tells Ray Velcoro to “own it” after he realizes he killed the wrong man all these years ago. I guess we all have to “own it”, recognize our mistakes, and move forward sometimes.

- Share your moral advice: “Character — the willingness to accept responsibility for one’s own life — is the source from which self-respect springs”.

- It’s worth exploring the subject further from a different angle. It doesn’t matter how many people have already written on self-respect or self-reliance – you can still write passionately about it.

- Whatever happens, you must take responsibility for it. Brave the storms of discontent.

27. Susan Sontag – Notes on Camp

I’ve never read anything so thorough and lucid about an artistic current. After reading this essay, you will know what camp is. But not only that – you will learn about so many artists you’ve never heard of. You will follow their traces and go to places where you’ve never been before. You will vastly increase your appreciation of art. It’s interesting how something written as a list could be so amazing. All the listicles we usually see on the web simply cannot compare with it.

- Talking about artistic sensibilities is a tough job. When you read the essay, you will see how much research, thought and raw intellect came into it. But that’s one of the reasons why people still read it today, even though it was written in 1964.

- You can choose an unorthodox way of expression in the medium for which you produce. For example, Notes on Camp is a listicle – one of the most popular content formats on the web. But in the olden days, it was uncommon to see it in print form.

- Just think about what is camp: “And third among the great creative sensibilities is Camp: the sensibility of failed seriousness, of the theatricalization of experience. Camp refuses both the harmonies of traditional seriousness and the risks of fully identifying with extreme states of feeling”.

28. Ralph Waldo Emerson – Self-Reliance

That’s the oldest one from the lot. Written in 1841, it still inspires generations of people. It will let you understand what it means to be self-made. It contains some of the most memorable quotes of all time. I don’t know why, but this one especially touched me: “Every true man is a cause, a country, and an age; requires infinite spaces and numbers and time fully to accomplish his design, and posterity seems to follow his steps as a train of clients”. Now isn’t it purely individualistic, American thought? Emerson told me (and he will tell you) to do something amazing with my life. The language it contains is a bit archaic, but that just adds to the weight of the argument. You can consider it to be a meeting with a great philosopher who shaped the ethos of the modern United States.

- You can start with a powerful poem that will set the stage for your work.

- Be free in your creative flow. Do not wait for the approval of others: “What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think. This rule, equally arduous in actual and in intellectual life, may serve for the whole distinction between greatness and meanness”.

- Use rhetorical questions to strengthen your argument: “I hear a preacher announce for his text and topic the expediency of one of the institutions of his church. Do I not know beforehand that not possibly say a new and spontaneous word?”

29. David Foster Wallace – Consider The Lobster

When you want simple field notes about a food festival, you needn’t send there the formidable David Foster Wallace. He sees right through the hypocrisy and cruelty behind killing hundreds of thousands of innocent lobsters – by boiling them alive. This essay uncovers some of the worst traits of modern American people. There are no apologies or hedging one’s bets. There’s just plain truth that stabs you in the eye like a lobster claw. After reading this essay, you may reconsider the whole animal-eating business.

- When it’s important, say it plainly and stagger the reader: “[Lobsters] survive right up until they’re boiled. Most of us have been in supermarkets or restaurants that feature tanks of live lobster, from which you can pick out your supper while it watches you point”.

- In your writing, put exact quotes of the people you’ve been interviewing (including slang and grammatical errors). It makes it more vivid, and interesting.

- You can use humor in serious situations to make your story grotesque.

- Use captions to expound on interesting points of your essay.

30. David Foster Wallace – The Nature of the Fun

The famous novelist and author of the most powerful commencement speech ever done is going to tell you about the joys and sorrows of writing a work of fiction. It’s like taking care of a mutant child that constantly oozes smelly liquids. But you love that child and you want others to love it too. It’s a very humorous account of what it means to be an author. If you ever plan to write a novel, you should read that one. And the story about the Chinese farmer is just priceless.

- Base your point on a chimerical analogy. Here, the writer’s unfinished work is a “hideously damaged infant”.

- Even in expository writing, you may share an interesting story to keep things lively.

- Share your true emotions (even when you think they won’t interest anyone). Often, that’s exactly what will interest the reader.

- Read the whole essay for marvelous advice on writing fiction.

31. Margaret Atwood – Attitude

This is not an essay per se, but I included it on the list for the sake of variety. It was delivered as a commencement speech at The University of Toronto, and it’s about keeping the right attitude. Soon after leaving university, most graduates have to forget about safety, parties, and travel and start a new life – one filled with a painful routine that will last until they drop. Atwood says that you don’t have to accept that. You can choose how you react to everything that happens to you (and you don’t have to stay in that dead-end job for the rest of your days).

- At times, we are all too eager to persuade, but the strongest persuasion is not forceful. It’s subtle. It speaks to the heart. It affects you gradually.

- You may be tempted to talk about a subject by first stating what it is not, rather than what it is. Try to avoid that.

- Simple advice for writers (and life in general): “When faced with the inevitable, you always have a choice. You may not be able to alter reality, but you can alter your attitude towards it”.

32. Jo Ann Beard – The Fourth State of Matter

Read that one as soon as possible. It’s one of the most masterful and impactful essays you’ll ever read. It’s like a good horror – a slow build-up, and then your jaw drops to the ground. To summarize the story would be to spoil it, so I recommend that you just dig in and devour this essay in one sitting. It’s a perfect example of “show, don’t tell” writing, where the actions of characters are enough to create the right effect. No need for flowery adjectives here.

- The best story you will tell is going to come from your personal experience.

- Use mysteries that will nag the reader. For example, at the beginning of the essay, we learn about the “vanished husband” but there’s no explanation. We have to keep reading to get the answer.

- Explain it in simple terms: “You’ve got your solid, your liquid, your gas, and then your plasma”. Why complicate?

33. Terence McKenna – Tryptamine Hallucinogens and Consciousness

To me, Terence McKenna was one of the most interesting thinkers of the twentieth century. His many lectures (now available on YouTube) attracted millions of people who suspect that consciousness holds secrets yet to be unveiled. McKenna consumed psychedelic drugs for most of his life and it shows (in a positive way). Many people consider him a looney, and a hippie, but he was so much more than that. He dared to go into the abyss of his psyche and come back to tell the tale. He also wrote many books (the most famous being Food Of The Gods ), built a huge botanical garden in Hawaii , lived with shamans, and was a connoisseur of all things enigmatic and obscure. Take a look at this essay, and learn more about the explorations of the subconscious mind.

- Become the original thinker, but remember that it may require extraordinary measures: “I call myself an explorer rather than a scientist because the area that I’m looking at contains insufficient data to support even the dream of being a science”.

- Learn new words every day to make your thoughts lucid.

- Come up with the most outlandish ideas to push the envelope of what’s possible. Don’t take things for granted or become intellectually lazy. Question everything.

34. Eudora Welty – The Little Store

By reading this little-known essay, you will be transported into the world of the old American South. It’s a remembrance of trips to the little store in a little town. It’s warm and straightforward, and when you read it, you feel like a child once more. All these beautiful memories live inside of us. They lay somewhere deep in our minds, hidden from sight. The work by Eudora Welty is an attempt to uncover some of them and let you get reacquainted with some smells and tastes of the past.

- When you’re from the South, flaunt it. It’s still good old English but sometimes it sounds so foreign. I can hear the Southern accent too: “There were almost tangible smells – licorice recently sucked in a child’s cheek, dill-pickle brine that had leaked through a paper sack in a fresh trail across the wooden floor, ammonia-loaded ice that had been hoisted from wet Croker sacks and slammed into the icebox with its sweet butter at the door, and perhaps the smell of still-untrapped mice”.

- Yet again, never forget your roots.

- Childhood stories can be the most powerful ones. You can write about how they shaped you.

35. John McPhee – The Search for Marvin Gardens

The Search for Marvin Gardens contains many layers of meaning. It’s a story about a Monopoly championship, but also, it’s the author’s search for the lost streets visible on the board of the famous board game. It also presents a historical perspective on the rise and fall of civilizations, and on Atlantic City, which once was a lively place, and then, slowly declined, the streets filled with dirt and broken windows.

- There’s nothing like irony: “A sign- ‘Slow, Children at Play’- has been bent backward by an automobile”.

- Telling the story in apparently unrelated fragments is sometimes better than telling the whole thing in a logical order.

- Creativity is everything. The best writing may come just from connecting two ideas and mixing them to achieve a great effect. Shush! The muse is whispering.

36. Maxine Hong Kingston – No Name Woman

A dead body at the bottom of the well makes for a beautiful literary device. The first line of Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name Is Red delivers it perfectly: “I am nothing but a corpse now, a body at the bottom of a well”. There’s something creepy about the idea of the well. Just think about the “It puts the lotion in the basket” scene from The Silence of the Lambs. In the first paragraph of Kingston’s essay, we learn about a suicide committed by uncommon means of jumping into the well. But this time it’s a real story. Who was this woman? Why did she do it? Read the essay.

- Mysterious death always gets attention. The macabre details are like daiquiris on a hot day – you savor them – you don’t let them spill.

- One sentence can speak volumes: “But the rare urge west had fixed upon our family, and so my aunt crossed boundaries not delineated in space”.

- It’s interesting to write about cultural differences – especially if you have the relevant experience. Something normal for us is unthinkable for others. Show this different world.

- The subject of sex is never boring.

37. Joan Didion – On Keeping A Notebook

Slouching Towards Bethlehem is one of the most famous collections of essays of all time. In it, you will find a curious piece called On Keeping A Notebook. It’s not only a meditation about keeping a journal. It’s also Didion’s reconciliation with her past self. After reading it, you will seriously reconsider your life’s choices and look at your life from a wider perspective.

- When you write things down in your journal, be more specific – unless you want to write a deep essay about it years later.

- Use the beauty of the language to relate to the past: “I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be; one of them, a seventeen-year-old, presents little threat, although it would be of some interest to me to know again what it feels like to sit on a river levee drinking vodka-and-orange-juice and listening to Les Paul and Mary Ford and their echoes sing ‘How High the Moon’ on the car radio”.

- Drop some brand names if you want to feel posh.

38. Joan Didion – Goodbye To All That

This one touched me because I also lived in New York City for a while. I don’t know why, but stories about life in NYC are so often full of charm and this eerie-melancholy-jazz feeling. They are powerful. They go like this: “There was a hard blizzard in NYC. As the sound of sirens faded, Tony descended into the dark world of hustlers and pimps.” That’s pulp literature but in the context of NYC, it always sounds cool. Anyway, this essay is amazing in too many ways. You just have to read it.

- Talk about New York City. They will read it.

- Talk about the human experience: “It did occur to me to call the desk and ask that the air conditioner be turned off, I never called, because I did not know how much to tip whoever might come—was anyone ever so young?”

- Look back at your life and reexamine it. Draw lessons from it.

39. George Orwell – Reflections on Gandhi

George Orwell could see things as they were. No exaggeration, no romanticism – just facts. He recognized totalitarianism and communism for what they were and shared his worries through books like 1984 and Animal Farm . He took the same sober approach when dealing with saints and sages. Today, we regard Gandhi as one of the greatest political leaders of the twentieth century – and rightfully so. But did you know that when asked about the Jews during World War II, Gandhi said that they should commit collective suicide and that it: “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” He also recommended utter pacifism in 1942, during the Japanese invasion, even though he knew it would cost millions of lives. But overall he was a good guy. Read the essay and broaden your perspective on the Bapu of the Indian Nation.

- Share a philosophical thought that stops the reader for a moment: “No doubt alcohol, tobacco, and so forth are things that a saint must avoid, but sainthood is also a thing that human beings must avoid”.

- Be straightforward in your writing – no mannerisms, no attempts to create ‘style’, and no invocations of the numinous – unless you feel the mystical vibe.

40. George Orwell – Politics and the English Language