Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Critical Thinking and other Higher-Order Thinking Skills

Critical thinking is a higher-order thinking skill. Higher-order thinking skills go beyond basic observation of facts and memorization. They are what we are talking about when we want our students to be evaluative, creative and innovative.

When most people think of critical thinking, they think that their words (or the words of others) are supposed to get “criticized” and torn apart in argument, when in fact all it means is that they are criteria-based. These criteria require that we distinguish fact from fiction; synthesize and evaluate information; and clearly communicate, solve problems and discover truths.

Why is Critical Thinking important in teaching?

According to Paul and Elder (2007), “Much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and that of which we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought.” Critical thinking is therefore the foundation of a strong education.

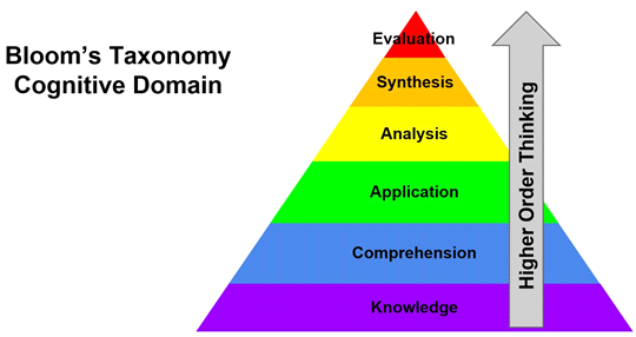

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy of thinking skills, the goal is to move students from lower- to higher-order thinking:

- from knowledge (information gathering) to comprehension (confirming)

- from application (making use of knowledge) to analysis (taking information apart)

- from evaluation (judging the outcome) to synthesis (putting information together) and creative generation

This provides students with the skills and motivation to become innovative producers of goods, services, and ideas. This does not have to be a linear process but can move back and forth, and skip steps.

How do I incorporate critical thinking into my course?

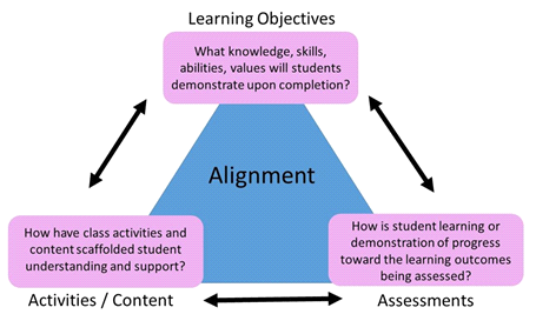

The place to begin, and most obvious space to embed critical thinking in a syllabus, is with student-learning objectives/outcomes. A well-designed course aligns everything else—all the activities, assignments, and assessments—with those core learning outcomes.

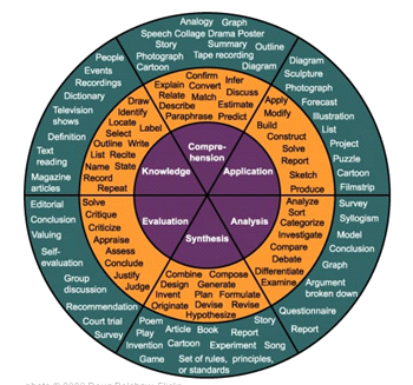

Learning outcomes contain an action (verb) and an object (noun), and often start with, “Student’s will....” Bloom’s taxonomy can help you to choose appropriate verbs to clearly state what you want students to exit the course doing, and at what level.

- Students will define the principle components of the water cycle. (This is an example of a lower-order thinking skill.)

- Students will evaluate how increased/decreased global temperatures will affect the components of the water cycle. (This is an example of a higher-order thinking skill.)

Both of the above examples are about the water cycle and both require the foundational knowledge that form the “facts” of what makes up the water cycle, but the second objective goes beyond facts to an actual understanding, application and evaluation of the water cycle.

Using a tool such as Bloom’s Taxonomy to set learning outcomes helps to prevent vague, non-evaluative expectations. It forces us to think about what we mean when we say, “Students will learn…” What is learning; how do we know they are learning?

The Best Resources For Helping Teachers Use Bloom’s Taxonomy In The Classroom by Larry Ferlazzo

Consider designing class activities, assignments, and assessments—as well as student-learning outcomes—using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide.

The Socratic style of questioning encourages critical thinking. Socratic questioning “is systematic method of disciplined questioning that can be used to explore complex ideas, to get to the truth of things, to open up issues and problems, to uncover assumptions, to analyze concepts, to distinguish what we know from what we don’t know, and to follow out logical implications of thought” (Paul and Elder 2007).

Socratic questioning is most frequently employed in the form of scheduled discussions about assigned material, but it can be used on a daily basis by incorporating the questioning process into your daily interactions with students.

In teaching, Paul and Elder (2007) give at least two fundamental purposes to Socratic questioning:

- To deeply explore student thinking, helping students begin to distinguish what they do and do not know or understand, and to develop intellectual humility in the process

- To foster students’ abilities to ask probing questions, helping students acquire the powerful tools of dialog, so that they can use these tools in everyday life (in questioning themselves and others)

How do I assess the development of critical thinking in my students?

If the course is carefully designed around student-learning outcomes, and some of those outcomes have a strong critical-thinking component, then final assessment of your students’ success at achieving the outcomes will be evidence of their ability to think critically. Thus, a multiple-choice exam might suffice to assess lower-order levels of “knowing,” while a project or demonstration might be required to evaluate synthesis of knowledge or creation of new understanding.

Critical thinking is not an “add on,” but an integral part of a course.

- Make critical thinking deliberate and intentional in your courses—have it in mind as you design or redesign all facets of the course

- Many students are unfamiliar with this approach and are more comfortable with a simple quest for correct answers, so take some class time to talk with students about the need to think critically and creatively in your course; identify what critical thinking entail, what it looks like, and how it will be assessed.

Additional Resources

- Barell, John. Teaching for Thoughtfulness: Classroom Strategies to Enhance Intellectual Development . Longman, 1991.

- Brookfield, Stephen D. Teaching for Critical Thinking: Tools and Techniques to Help Students Question Their Assumptions . Jossey-Bass, 2012.

- Elder, Linda and Richard Paul. 30 Days to Better Thinking and Better Living through Critical Thinking . FT Press, 2012.

- Fasko, Jr., Daniel, ed. Critical Thinking and Reasoning: Current Research, Theory, and Practice . Hampton Press, 2003.

- Fisher, Alec. Critical Thinking: An Introduction . Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Paul, Richard and Linda Elder. Critical Thinking: Learn the Tools the Best Thinkers Use . Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

- Faculty Focus article, A Syllabus Tip: Embed Big Questions

- The Critical Thinking Community

- The Critical Thinking Community’s The Thinker’s Guides Series and The Art of Socratic Questioning

Quick Links

- Developing Learning Objectives

- Creating Your Syllabus

- Active Learning

- Service Learning

- Case Based Learning

- Group and Team Based Learning

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom

- Effective PowerPoint Design

- Hybrid and Hybrid Limited Course Design

- Online Course Design

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

Course details

Critical thinking: an introduction.

This is an In-person course which requires your attendance to the weekly meetings which take place in Oxford.

In print, online and in conversation, we frequently encounter conflicting views on important issues: from climate change, vaccinations and current political events to economic policy, healthy lifestyles and parenting. It can be difficult to know how to make up one’s own mind when confronted with such diverse viewpoints.

This course teaches you how to critically engage with different points of view. You are given some guidelines that will help you decide to what extent to trust the person, organisation, website or publication defending a certain position. You are also shown how to assess others’ views and arrive at your own point of view through reasoning. We discuss examples of both reasoning about facts and the reasoning required in making practical decisions. We distinguish risky inferences with probable conclusions from risk-free inferences with certain conclusions. You are shown how to spot and avoid common mistakes in reasoning.

No previous knowledge of critical thinking or logic is needed. This course will be enjoyed by those who relish the challenge of thinking rationally and learning new skills. The skills and concepts taught will also be useful when studying other areas of philosophy.

Programme details

Course starts: 2 Oct 2024

Week 1: What is critical thinking? What is the difference between reasoning and other ways of forming beliefs or making decisions?

Week 2: What is a logical argument? How do arguments differ from conditionals, explanations and rhetoric?

Week 3: Certainty versus high probability: the distinction between deductive and inductive reasoning.

Week 4: Deductive validity and logical form.

Week 5: When do arguments rely on hidden premises? What is probability?

Week 6: Inductive generalisations and reasoning about causes.

Week 7: Inference to the best explanation.

Week 8: Practical reasoning: Reasoning about what to do.

Week 9: When is it appropriate to believe what others tell you? What is the significance of expertise?

Week 10: Putting it all together: We analyse and assess longer passages of reasoning.

Recommended reading

All weekly class students may become borrowing members of the Rewley House Continuing Education Library for the duration of their course. Prospective students whose courses have not yet started are welcome to use the Library for reference. More information can be found on the Library website.

There is a Guide for Weekly Class students which will give you further information.

Availability of titles on the reading list (below) can be checked on SOLO , the library catalogue.

Preparatory reading:

- Critical Reasoning: A Romp Through the Foothills of Logic for Complete Beginners / Talbot, M

- Critical Thinking: An Introduction to Reasoning Well / Watson, J C and Arp R

Recommended Reading List

Digital Certification

To complete the course and receive a certificate, you will be required to attend at least 80% of the classes on the course and pass your final assignment. Upon successful completion, you will receive a link to download a University of Oxford digital certificate. Information on how to access this digital certificate will be emailed to you after the end of the course. The certificate will show your name, the course title and the dates of the course you attended. You will be able to download your certificate or share it on social media if you choose to do so.

If you are in receipt of a UK state benefit, you are a full-time student in the UK or a student on a low income, you may be eligible for a reduction of 50% of tuition fees. Please see the below link for full details:

Concessionary fees for short courses

Dr Andrea Lechler

Andrea Lechler holds a degree in Computational Linguistics, an MSc in Artificial Intelligence, and an MA and PhD in Philosophy. She has extensive experience of teaching philosophy for OUDCE and other institutions. Her website is www.andrealechler.com.

Course aims

To help students improve their critical thinking skills.

Course Objectives:

- To help students reflect on how people reason and how they try to persuade others of their views.

- To make students familiar with the principles underlying different types of good reasoning as well as common mistakes in reasoning.

- To present some guidelines for identifying trustworthy sources of information.

Teaching methods

The tutor will present the course content in an interactive way using plenty of examples and exercises. Students are encouraged to ask questions and participate in class discussions and group work. To consolidate their understanding of the subject they will be assigned further exercises as homework.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the course students will be expected to:

- be able to pick out and analyse passages of reasoning in texts and conversations

- understand the most important ways of assessing the cogency of such reasoning

- know how to assess the trustworthiness of possible sources of information.

Assessment methods

Assessment is based on a set of exercises similar to those discussed in class. One set of homework exercises can be submitted as a practice assignment.

Coursework is an integral part of all weekly classes and everyone enrolled will be expected to do coursework in order to benefit fully from the course. Only those who have registered for credit will be awarded CATS points for completing work to the required standard.

Students must submit a completed Declaration of Authorship form at the end of term when submitting their final piece of work. CATS points cannot be awarded without the aforementioned form - Declaration of Authorship form

Application

To earn credit (CATS points) for your course you will need to register and pay an additional £30 fee per course. You can do this by ticking the relevant box at the bottom of the enrolment form or when enrolling online.

Please use the 'Book' or 'Apply' button on this page. Alternatively, please complete an enrolment form (Word) or enrolment form (Pdf) .

Level and demands

The Department's Weekly Classes are taught at FHEQ Level 4, i.e. first year undergraduate level, and you will be expected to engage in a significant amount of private study in preparation for the classes. This may take the form, for instance, of reading and analysing set texts, responding to questions or tasks, or preparing work to present in class.

Credit Accumulation and Transfer Scheme (CATS)

To earn credit (CATS points) you will need to register and pay an additional £30 fee per course. You can do this by ticking the relevant box at the bottom of the enrolment form or when enrolling online. Students who register for CATS points will receive a Record of CATS points on successful completion of their course assessment.

Students who do not register for CATS points during the enrolment process can either register for CATS points prior to the start of their course or retrospectively from the January 1st after the current full academic year has been completed. If you are enrolled on the Certificate of Higher Education you need to indicate this on the enrolment form but there is no additional registration fee.

Terms & conditions for applicants and students

Information on financial support

IMAGES

VIDEO