- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Sign in to an additional subscriber account

- This account has no valid subscription for this site.

Article contents

Progressives and progressivism in an era of reform.

- Maureen A. Flanagan Maureen A. Flanagan Department of Humanities, Illinois Institute of Technology

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.84

- Published online: 05 August 2016

The decades from the 1890s into the 1920s produced reform movements in the United States that resulted in significant changes to the country’s social, political, cultural, and economic institutions. The impulse for reform emanated from a pervasive sense that the country’s democratic promise was failing. Political corruption seemed endemic at all levels of government. An unregulated capitalist industrial economy exploited workers and threatened to create a serious class divide, especially as the legal system protected the rights of business over labor. Mass urbanization was shifting the country from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial one characterized by poverty, disease, crime, and cultural clash. Rapid technological advancements brought new, and often frightening, changes into daily life that left many people feeling that they had little control over their lives. Movements for socialism, woman suffrage, and rights for African Americans, immigrants, and workers belied the rhetoric of the United States as a just and equal democratic society for all its members.

Responding to the challenges presented by these problems, and fearful that without substantial change the country might experience class upheaval, groups of Americans proposed undertaking significant reforms. Underlying all proposed reforms was a desire to bring more justice and equality into a society that seemed increasingly to lack these ideals. Yet there was no agreement among these groups about the exact threat that confronted the nation, the means to resolve problems, or how to implement reforms. Despite this lack of agreement, all so-called Progressive reformers were modernizers. They sought to make the country’s democratic promise a reality by confronting its flaws and seeking solutions. All Progressivisms were seeking a via media, a middle way between relying on older ideas of 19th-century liberal capitalism and the more radical proposals to reform society through either social democracy or socialism. Despite differences among Progressives, the types of Progressivisms put forth, and the successes and failures of Progressivism, this reform era raised into national discourse debates over the nature and meaning of democracy, how and for whom a democratic society should work, and what it meant to be a forward-looking society. It also led to the implementation of an activist state.

- Progressives

- Progressivisms

- urbanization

- immigration

The reform impulse of the decades from the 1890s into the 1920s did not erupt suddenly in the 1890s. Previous movements, such as the Mugwump faction of the Republican Party and the Knights of Labor, had challenged existing conditions in the 1870s and 1880s. Such earlier movements either tended to focus on the problems of a particular group or were too small to effect much change. The 1890s Populist Party’s concentration on agrarian issues did not easily resonate with the expanding urban population. The Populists lost their separate identity when the Democratic Party absorbed their agenda. The reform proposals of the Progressive era differed from those of these earlier protest movements. Progressives came from all strata of society. Progressivism aimed to implement comprehensive systemic reforms to change the direction of the country.

Political corruption, economic exploitation, mass migration and urbanization, rapid technological advancements, and social unrest challenged the rhetoric of the United States as a just and equal society. Now groups of Americans throughout the country proposed to reform the country’s political, social, cultural, and economic institutions in ways that they believed would address fundamental problems that had produced the inequities of American society.

Progressives did not seek to overturn capitalism. They sought to revitalize a democratic promise of justice and equality and to move the country into a modern Progressive future by eliminating or at least ameliorating capitalism’s worst excesses. They wanted to replace an individualistic, competitive society with a more cooperative, democratic one. They sought to bring a measure of social justice for all people, to eliminate political corruption, and to rebalance the relationship among business, labor, and consumers by introducing economic regulation. 1 Progressives turned to government to achieve these objectives and laid the foundation for an increasingly powerful state.

Social Justice Progressivism

Social justice Progressives wanted an activist state whose first priority was to provide for the common welfare. Jane Addams argued that real democracy must operate from a sense of social morality that would foster the greater good of all rather than protect those with wealth and power. 2 Social justice Progressivism confronted two problems to securing a democracy based on social morality. Several basic premises that currently structured the country had to be rethought, and social justice Progressivism was promoted largely by women who lacked official political power.

Legal Precedent or Social Realism

The existing legal system protected the rights of business and property over labor. 3 From 1893 , when Florence Kelley secured factory legislation mandating the eight-hour workday for women and teenagers and outlawing child labor in Illinois factories, social justice Progressives faced legal obstacles as business contested such legislation. In 1895 , the Supreme Court in Ritchie v. People ruled that such legislation violated the “freedom of contract” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court confined the police power of the state to protecting immediate health and safety, not groups of people in industries. 4 Then, in the 1905 case Lochner v. New York , the Court declared that the state had no interest in regulating the hours of male bakers. To circumvent these rulings, Kelley, Josephine Goldmark, and Louis Brandeis contended that law should address social realities. The Brandeis brief to the Supreme Court in 1908 , in Muller v. Oregon , argued for upholding Oregon’s eight-hour law for women working in laundries because of the debilitating physical effects of such work. When the Court agreed, social justice Progressives hoped this would be the opening wedge to extend new rights to labor. The Muller v. Oregon ruling had a narrow gender basis. It declared that the state had an interest in protecting the reproductive capacities of women. Henceforth, male and female workers would be unequal under the law, limiting women’s economic opportunities across the decades, rather than shifting the legal landscape. Ruling on the basis of women’s reproductive capacities, the Court made women socially inferior to men in law and justified state-sponsored interference in women’s control of their bodies. 5

Role of the State to Protect and Foster

Women organized in voluntary groups worked to identify and attack the problems caused by mass urbanization. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs ( 1890 ) coordinated women’s activities throughout the country. Social justice Progressives lobbied municipal governments to enact new ordinances to ameliorate existing urban conditions of poverty, disease, and inequality. Chicago women secured the nation’s first juvenile court ( 1899 ). 6 Los Angeles women helped inaugurate a public health nursing program and secure pure milk regulations for their city. Women also secured municipal public baths in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities. Organized women in Philadelphia and Dallas were largely responsible for their cities implementing new clean water systems. Women set up pure milk stations to prevent infant diarrhea and organized infant welfare societies. 7

Social justice Progressives sought national legislation to protect consumers from the pernicious effects of industrial production outside of their immediate control. In 1905 , the General Federation of Women’s Clubs initiated a letter-writing campaign to pressure Congress to pass pure food legislation. Standard accounts of the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and pure milk ordinances generally credit male professionals with putting in place such reforms, but female social justice Progressives were instrumental in putting this issue before the country. 8

Social justice Progressives sought a ban on child labor and protections for children’s health and education. They argued that no society could progress if it allowed child labor. In 1912 they persuaded Congress to establish a federal Children’s Bureau to investigate conditions of children throughout the country. Julia Lathrop first headed the bureau, which was thenceforth dominated by women. Nonetheless, when Congress passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act ( 1916 ), banning interstate commerce in products made with child labor, a North Carolina man immediately sued, arguing that it deprived him of property in his son’s labor. The Supreme Court ( 1918 ) ruled the law unconstitutional because it violated state powers to regulate conditions of labor. A constitutional amendment banning child labor ( 1922 ) was attacked by manufacturers and conservative organizations protesting that it would give government power over children. Only four states ratified the amendment. 9

Woman suffrage was crucial for social justice Progressives as both a democratic right and because they believed it essential for their agenda. 10 When suffrage left elected officials uncertain about the power of women’s votes in 1921 , Congress passed the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infant Welfare bill, which provided federal funds for maternal and infant health. The American Medical Association opposed the bill as a violation of its expertise. Businessmen and political leaders protested that the federal government should not interfere in health care and objected that it would raise taxes. Congress made Sheppard-Towner a “sunset” act to run for five years, after which it would decide whether to renew it. Congress temporarily extended it but ended the funding in 1929 , even though the country’s infant mortality rate exceeded that of six other industrial countries. The hostility of the male-dominated American Medical Association and the Public Health Service to Sheppard-Towner and to its administration by the Children’s Bureau, along with attacks against the social justice network of women’s organizations as a communist conspiracy to undermine American society, doomed the legislation. 11

New Practices of Democracy

Women established settlement houses, voluntary associations, day nurseries, and community, neighborhood, and social centers as venues in which to practice participatory democracy. These venues intended to bring people together to learn about one another and their needs, to provide assistance for those needing help, and to lobby their governments to provide social goods to people. This was not reform from the bottom; middle-class women almost always led these venues. Most of these efforts were also racially exclusive, but African American women established venues of their own. In Atlanta, Lugenia Hope, who had spent time at Chicago’s Hull House, established the Atlanta Neighborhood Union in 1908 to organize the city’s African American women on a neighborhood basis. Hope urged women to investigate the problems of their neighborhoods and bring their issues to the municipal government. 12

The National Consumers’ League (NCL, 1899 ) practiced participatory democracy on the national level. Arising from earlier working women’s societies and with Florence Kelley at its head, the NCL investigated working conditions and urged women to use their consumer-purchasing power to force manufacturers to institute new standards of production. The NCL assembled and published “white lists” of those manufacturers found to be practicing good employment standards and awarded a “white label” to factories complying with such standards. The NCL’s tactics were voluntary—boycotts were against the law—and they did not convince many manufacturers to change their practices. Even so, such tactics drew more women into the social justice movement, and the NCL’s continuous efforts were rewarded in New Deal legislation. 13

A group of working women and settlement-house residents formed the National Women’s Trade Union League (NWTUL, 1903 ) and organized local affiliates to work for unionization in female-dominated manufacturing. 14 Middle-class women walked the picket lines with striking garment workers and waitresses in New York and Chicago and helped secure concessions from manufacturers. The NWTUL forced an official investigation into the causes of New York City’s Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire ( 1911 ), in which almost 150 workers, mainly young women, died. Members of the NWTUL were organizers for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. Despite these participatory venues, much literature on such movements emphasizes male initiatives and fails to appreciate gender differences. The public forums movement promoted by men, such as Charles Sprague Smith and Frederic Howe, was a top-down effort in which prominent speakers addressed pressing issues of the day to teach the “rank and file” how to practice democracy. 15 In Boston, Mary Parker Follett promoted participatory democracy through neighborhood centers organized and run by residents. Chicago women’s organizations fostered neighborhood centers as spaces for residents to gather and discuss neighborhood needs. 16

Suffrage did not provide the political power women had hoped for, but female social justice Progressives occupied key offices in the New Deal administration. They helped write national anti-child labor legislation, minimum wage and maximum hour laws, aid to dependent children, and elements of the Social Security Act. Such legislation at least partially fulfilled the social justice Progressive agenda that activist government provide social goods to protect daily life against the vagaries of the capitalist marketplace.

Political Progressivism

Political Progressivism was a structural-instrumental approach to reform the mechanisms and exercise of politics to break the hold of political parties. Its adherents sought a well-ordered government run by experts to undercut a political patronage system that favored trading votes for services. Political Progressives believed that such reforms would enhance democracy.

Mechanisms and Processes of Electoral Democracy

The Wisconsin Idea promoted by the state’s three-time governor Robert La Follette exemplified the political Progressives’ approach to reform. The plan advocated state-level reforms to electoral procedures. A key proposal of the Wisconsin Idea was to replace the existing party control of all nominations with a popular direct primary. Wisconsin became the first state to require the direct primary. The plan also proposed giving voters the power to initiate legislation, hold referenda on proposed legislation, and recall elected officials. Wisconsin voters adopted these proposals by 1911 , 17 although Oregon was the first state to adopt the initiative and referendum, in 1902 . 18

The political Progressives attacked a patronage politics that filled administrative offices with faithful party supporters, awarded service franchises to private business, and solicited bribes in return for contracts. Political Progressives proposed shifting to merit-based government by experts provided by theoretically nonpartisan appointed commissions or city managers systems that would apply businesslike expertise and fiscal efficiency to government. They proposed replacing city councils elected by districts (wards) with citywide at-large elections, creating strong mayor systems to undercut the machinations of city councils, and reducing the number of elective offices. They also sought new municipal charters and home-rule powers to give cities more control over their governing authority and taxing power. 19

Political Progressives were mainly men organized into new local civic federations, city clubs, municipal reform leagues, and municipal research bureaus and into new national groups such as the National Municipal League. They attended national conferences such as the National Conference on City Planning, discussing topics of concern to political Progressives. The National Municipal League formulated a model charter to reorganize municipal government predicated on home rule and argued that its proposals would provide good tools for democracy. 20

In general, only small cities such as Galveston, Texas, and Des Moines, Iowa, or new cities such as Phoenix, Arizona, where such political Progressives dominated elections, adopted the city-manager and commission governments. 21 Other cities elected reform mayors, such as Tom Johnson of Cleveland, Ohio, who placed the professional experts Frederic Howe and Edward W. Bemis into his administration. 22 Charter reform, home rule, and at-large election movements were more complicated in big cities. They failed in Chicago. 23 Boston switched to at-large elections, but the shift in mechanisms did lessen political party control. A new breed of politicians who appealed to interest group politics gained control rather than rule by experts. 24

Good Government by Experts

Focus on good government reform earned these men the rather pejorative nickname of “goo-goos.” These Progressives argued that only the technological expertise of professional engineers and professional bureaucrats could design rational and economically efficient ordinances for solving urban problems. When corporate interests challenged antipollution ordinances and increased government regulation as causing undue hardship for manufacturers, political Progressives countered with economic answers. Pollution was an economic problem: it caused the city to suffer economic waste and inefficiency, and it cost the city and its taxpayers money. 25 In Pittsburgh, the Mellon Institute Smoke Investigation marshaled scientific expertise to measure soot fall in the city and to calculate how costly smoke pollution might be to the city. 26 The Supreme Court in Northwestern Laundry v. Des Moines ( 1915 ) ruled that there were no valid constitutional objections to state power to regulate pollution. 27

The political Progressives’ cost-benefit approach to regulation clashed with the social justice idea that protecting the public health should decide pollution regulation. The Pittsburgh Ladies Health Protective Association argued that smoke pollution was a general health hazard. 28 The Chicago women’s Anti-Smoke League called smoke pollution a threat to daily life and common welfare, as coal soot fell on food and in homes and was breathed in by children. They demanded immediate strict antismoke ordinances and inspectors to vigorously inspect and enforce the ordinances. The league urged all city residents to monitor pollution in their neighborhoods. 29 The Baltimore Women’s Civic League made smoke abatement a principal target for improving living and working conditions. 30 The cost-benefit argument usually won out over the health-first one.

For political Progressives, good government also meant using professional expertise to plan city growth and reorder the urban built environment. They abandoned an earlier City Beautiful movement that focused on cultural and aesthetic beautification in favor of systematic planning by architects, engineers, and city planners to secure the economic development desired by business. 31 Daniel Burnham’s Chicago Plan ( 1909 ) was the work of a committee of men selected by the city’s Commercial Club. 32 Experts crafted new master plans to guarantee urban functionality and profitability through “creative destruction,” to build new transportation and communication networks, erect new grand civic buildings and spaces, and zone the city’s functions into distinct sectors. They proposed new street configurations to facilitate the movement of goods and people. 33 As the profession of urban planning developed, cities sought out planners such as Harland Bartholomew to formulate new master plans. 34

New York’s Mary Simkhovitch contested this approach and urged planning on the neighborhood level, with professionals consulting with the people. She stressed that no plan was good if it emphasized only economy. Simkhovitch and Florence Kelley organized the first National Conference on City Planning ( 1909 ) around the theme of planning for social needs. Simkhovitch was the only woman to address the gathering. All the male speakers emphasized planning for economic development. As architects, lawyers, and engineers, and new professional planners such as John Nolen and George Ford dominated the planning conferences, Simkhovitch and Kelley withdrew. 35

The democratic reform theories of Frederic Howe and Mary Parker Follett reflected competing ideas about political Progressivism and urban reform. Howe believed that democracy was a political mechanism that, if properly ordered and led by experts, would restore the city to the people. The key to achieving good government and democracy was municipal home rule. Once freed from state interference, his theoretical city republic would decide in the best interests of its residents, making city life orderly and thereby more democratic. 36 For Follett, democracy was embedded in social relations, and the city was the hope of democracy because it could be organized on the neighborhood level. There people would apply democracy collectively and create an orderly society. 37 Throughout the country, municipal political reform was driven primarily by groups of men. Women and their ideas were consistently pushed to the margins of political Progressivism. 38

Social Science Expertise

Social science expertise gave political Progressives a theoretical foundation for cautious proposals to create a more activist state. University of Wisconsin political economist Richard Ely; his former student John R. Commons; political scientist Charles McCarthy, who authored the Wisconsin Idea; and University of Michigan political economist Henry C. Adams, among others, filled the role of social science expert. Social scientists founded new disciplinary organizations, such as the American Economics Association. This association organized the American Association of Labor Legislation (AALL). Commons, University of Chicago sociology professor Charles R. Henderson, and Commons’ student John B. Andrews were prominent members. The AALL focused on workers’ health, compensation, and insurance, in contrast to the NCL emphasis on investigation and working conditions. 39 Frederic Howe, with a PhD in history and political science from Johns Hopkins, became a foremost theorist for municipal reform based on his social science theories. John Dewey promulgated new theories of democracy and education. Professional social scientists composed a tight circle of men who created a space between academia and government from which to advocate for reform. 40 They addressed each other, trained their students to follow their ideas, and rarely spoke to the larger public. 41

Sophonisba Breckinridge, Frances Kellor, Edith Abbott, and Katherine Davis were trained at the University of Chicago in political economy and sociology. Abbott briefly held an academic position at Wellesley, but she resigned to join the other women in applying her training to social research and social activism. Their expertise laid the foundation for the profession of social work. As grassroots activists, they worked with settlement house residents such as Jane Addams and Mary Simkhovitch, joined women’s voluntary organizations, investigated living and working conditions, and carved out careers in social welfare. 42

Male social scientists dismissed women’s expertise and eschewed grassroots work. 43 Breckinridge had earned a magna cum laude PhD in political science and economics, but she received no offers of an academic position, unlike her male colleagues. She was kept on at the university, but by 1920 the sociology department directed social sciences away from seeking practical solutions to everyday life that had linked scholarly inquiry with social responsibility. The female social scientists who had formed an intellectual core of the sociology department were put into a School of Social Services Administration and ultimately segregated into the division of social work. 44

Economic Progressivism

Economic Progressives identified unregulated corporate monopoly capitalism as a primary source of the country’s troubles. 45 They proposed a new regulatory state to mitigate the worst aspects of the system. Reforming the banking and currency systems, pursuing some measure of antitrust (antimonopoly) legislation, shifting from a largely laissez-faire economy, and moderately restructuring property relations would produce government in the public interest.

Antimonopoly Progressivism

Antimonopoly Progressivism required rethinking the relationship between business and government, introducing new legislation, and modifying a legal system that consistently sided with business. Congress and the presidency had to take leadership roles, but below them were Progressive groups such as the National Civic Federation, the NCL, and the General Federation of Women’s Clubs pushing for significant policy change. These Progressives believed collusion between a small number of capitalist industrialists and politicians had badly damaged democracy. They especially feared that the system threatened to lead to class warfare.

The Interstate Commerce Act ( 1887 ) and the Sherman Antitrust Act ( 1890 ) began to consider the problems of unregulated laissez-faire capitalism and monopoly in restraint of trade. As president, Theodore Roosevelt ( 1901–1909 ) used congressional power to regulate commerce to attack corporate monopolistic restraint of trade. The Elkins Act ( 1903 ) gave Congress the power to regulate against predatory business practices; the Hepburn Act ( 1906 ) gave it authority to regulate railroad rates; the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act ( 1906 ) did the same for those industries. Roosevelt created the Department of Commerce and Labor ( 1903 ) to oversee interstate corporate practices and in 1906 empowered the Department of Agriculture to inspect and set standards in meat production, a move that led eventually to the Food and Drug Administration.

Presidential Progressivism

Roosevelt considered the president to be the guardian of the public welfare. His approach to conservation was a primary example of how he applied this belief. He agreed with the arguments of social scientists, professional organizations of engineers, and forestry bureau chief Gifford Pinchot that careful and efficient management and administration of natural resources was necessary to guarantee the country’s economic progress and preserve democratic opportunity. Roosevelt appointed a Public Lands Commission to manage public land in the West and appointed a National Conservation Commission to inventory the country’s resources so that sound business practices could be implemented. The commission’s three-volume report relied on scientific and social scientific methods to examine conservation issues. 46

William Howard Taft ( 1909–1913 ) refused to support further work by the Conservation Commission. He rejected new conservation proposals as violating congressional authority and possessing no legal standing. Taft’s administrative appointments, including Interior Secretary Richard Ballinger, favored opening public lands to more private development. Taft’s Progressivism was the more conservative Republican approach that focused on breaking up trusts because they were bad for business. 47 Taft sided with business when he signed the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act ( 1909 ), which kept high tariffs on many essential goods that Progressives wanted reduced to aid consumers and small manufacturers. 48

In 1912 , the Republican Party split between Roosevelt and Taft. Political, economic, and social justice Progressives, including Robert La Follette, Charles McCarthy, Jane Addams, Frances Kellor, and George Perkins, a partner at J. P. Morgan and Company, helped establish the Progressive Party. They nominated Roosevelt, who envisioned a platform of “New Nationalism,” which promised to govern in the public interest and provide economic prosperity as a basic foundation of democratic citizenship. 49 Addams was unhappy with Roosevelt’s economic emphasis, but she saw him as social Progressives’ best hope.

Woodrow Wilson and Roosevelt received two-thirds of the vote, while Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs secured 6 percent of the votes. The election results indicated that the general population supported a middle way between socialism and Taft’s big business Progressivism. Wilson’s ( 1913–1921 ) “New Freedom” platform promised to curb the power of big business and close the growing wealth gap. As senator, La Follette helped push through Wilson’s reform legislation. The Clayton Antitrust Act ( 1914 ), the Federal Trade Commission ( 1914 ), and the Federal Reserve Act ( 1913 ) each curbed the power of big business and regulated banking. The Sixteenth Amendment ( 1913 ) authorized the federal income tax. The Seventeenth Amendment ( 1913 ) provided for the direct election of state legislators, who had previously been appointed by state legislatures.

Trade Union Progressivism

Under Samuel Gompers, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) fought to secure collective bargaining rights for male trade unionists. The AFL rejected the AALL proposals for worker compensation and insurance and never supported national worker compensation laws, although local federations supported state-level legislation. 50 Gompers preferred working with businessmen and politicians to secure the right to collective bargaining, the eight-hour day, and a voice for labor in production. The AFL never tried to form a Labor Party but advocated putting a labor agenda into mainstream party politics. 51 The Clayton Antitrust Act, which acknowledged that unions had the right to peaceful and lawful actions, was a victory for trade union Progressivism. The act did not provide everything that Gompers had demanded. Only New Deal legislation would offer more extensive protections to unions.

Gompers and the AFL rejected the AALL’s ideas, fearing that a more activist government might extend to regulating the labor of women and children. The AFL wanted sufficient economic security for white male workers, to move women out of the labor force. 52 Other labor Progressives sought the same end. Louis Brandeis and Father John Ryan promoted the living wage as a right of citizenship for male workers. Ryan acknowledged that unmarried women workers were entitled to a living wage, but he wanted labor reform to secure a family wage so that men would marry and families would produce children. 53 Hostile to organizing women, Gompers forced NWTUL leader Margaret Dreier Robins off the executive board of the Chicago Federation of Labor. 54

Municipal Ownership

On the local level, economic Progressives sought a middle way between socialism and the AFL’s single-minded trade unionism. AFL affiliates and Progressive politicians such as Cleveland’s Tom Johnson favored a municipal democracy that gave voters new powers. Municipal ownership of public utilities such as street railways promised the working class a way to protect their labor through the ballot. 55 Such reform would also destroy the franchise system. In Los Angeles, labor and socialists crafted a labor/socialist ticket to challenge the business/party control of the city and enact municipal ownership. A socialist administration in Milwaukee appealed to class interests to support an agenda that included municipal ownership. In Chicago, socialist Josephine Kaneko argued that she did not see much difference between socialism and women’s Progressive agenda for reform to benefit the common welfare. 56 Despite such flirtations between labor and socialists, labor remained attached to the Democratic Party.

Some cities achieved a measure of municipal ownership. Most middle-class urban Progressives deemed municipal ownership too socialist. They favored state economic regulation, led by experts, rather than ownership to break the monopoly in public utilities. 57

International Progressivism

Progressivism fostered new international engagement. The economic imperative to secure supplies of raw materials for industrial production, a messianic approach of bringing cultural and racial civilization around the globe, and belief in an international Progressivism that focused on international cooperation all pushed Progressives to think globally.

Securing Economic Progress

Although he was generally against Progressivism, President William McKinley annexed Hawaii ( 1898 ), saying that the country needed it even more than it had needed California. 58 The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine ( 1904 ) declared that intervention in the Caribbean was necessary to secure economic stability and forestall foreign interference in the area. Progressive Herbert Croly believed that the country needed to forcibly pacify some areas in the world in order for the United States to establish an American international system. 59 The Progressive Party platform ( 1912 ) declared it imperative to the people’s welfare that the country expand its foreign commerce. Between 1898 and 1941 , the United States invaded Cuba, acquired the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, took possession of Puerto Rico, colonized the Philippines and several Pacific islands, encouraged Panama to rebel against Colombia so that the United States could build the Panama Canal, invaded Mexico to protect oil interests, and intervened in Haiti, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. To protect its possessions in the Pacific, Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Elihu Root finalized the Root-Takahira Agreement ( 1908 ), which acknowledged Japan’s control of Korea in return for its noninterference in the Philippines. American imperialism based on economic and financial desires became referred to as “Dollar Diplomacy.” 60

Mission of Civilization

Race, paternalism, and masculinity characterized elements of international Progressivism. Senator Albert Beveridge had supported Progressive proposals to abolish child labor and had favored regulating business and granting more rights to labor, but he viewed Filipinos as too backward to understand democracy and self-government. The United States was God’s chosen nation, with a divine mission to civilize the world; it should exercise its “spirit of progress” to organize the world. 61 William Jennings Bryan had previously been an anti-imperialist, but later, as Wilson’s secretary of state, he advocated intervening in Latin America to tutor backward people in self-government. 62 In speeches and writings, Roosevelt stressed that new international possessions required men to accept the strenuous life of responsibility for other people in order to maintain American domination of the world. 63 Social science likened Filipino men to children lacking the vigorous manhood necessary for self-government. 64 Beveridge contended that it was government’s responsibility to manufacture manhood. Empire could be the new frontier of white masculinity. 65 Roosevelt concluded a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” ( 1907 ) in which Japan agreed to stop issuing passports to Japanese laborers to immigrate to the United States.

Democracy and International Cooperation

A cadre of Progressives who had worked to extend their ideals into an international context did not welcome imperialism, dollar diplomacy, and war. 66 Addams rejected war as an anachronism that failed to produce a collective responsibility. La Follette rejoiced that failures in dollar diplomacy elevated humanity over property. Suffragists compared their lack of the vote to the plight of Filipinos. Belle Case La Follette opposed incursion into Mexico and denounced all militarism as driven by greed, suspicion, and love of power. 67

Many Progressives opposed war as an assault on an international collective humanity. Women organized peace marches and founded a Women’s Peace Party. Addams, Kelley, Frederic Howe, Lillian Wald of New York’s Henry Street Settlement, and Paul Kellogg, editor of the Progressive Survey , formed the American Union Against Militarism. 68 Addams, Simkhovitch, the sociologist Emily Greene Balch, and labor leader Leonora O’Reilly attended the International Women’s Peace Conference at The Hague in spring 1915 . Florence Kelley was denied a passport to travel. 69 The work of the American Red Cross in Europe during and after the war reflected the humanitarian collective impulse of Progressivism. 70

Entry into World War I, President Wilson’s assertion that it would make the world safe for democracy, and a growing xenophobia that demanded 100 percent loyalty produced a Progressive crisis. Addams remained firm against the war as antihumanitarian and was vilified for her pacifism. 71 La Follette voted against the declaration of war, charging that it was being promoted by business desires and that it was absurd to believe that it would make the world safe for democracy. He was accused of being pro-German, and Theodore Roosevelt said that he should be hung. 72 Labor leader Morris Hillquit and Florence Kelley formed the People’s Council of America to continue to pressure for peace. Under pressure to display patriotism, Progressive opposition to the war crumbled. Paul Kellogg declared that it was time to combat European militarism. The American Union Against Militarism dissolved. Herbert Croly’s New Republic urged the country to take a more active role in the war to create a new international league of peace and assume leadership of democratic nations. John Dewey proclaimed it a war of peoples, not armies, and stated that international reform would follow its conclusion. 73

Other Progressives comforted themselves that once the war was won, they could recommit to democratic agendas. Kelley, Grace Abbott, Josephine Goldmark, and Julia Lathrop helped organize the home front to maintain Progressive ideals. They monitored the condition of women workers, sat on the war department’s board controlling labor standards, and drafted insurance policies for military personnel. Suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt volunteered for the Women’s Advisory Committee of the Council of National Defense. Walter Lippmann worked on government projects. City planner John Nolen designed housing communities for war workers under the newly constituted United States Housing Corporation. 74

Suffragists protested the lack of democracy in the United States. As Wilson refused to support woman suffrage, members of the National Woman’s Party, led by Alice Paul, picketed the White House in protest. Picketers were arrested, Paul was put in solitary confinement in a psychiatric ward, and several women on a hunger strike were force-fed. Wilson capitulated to public outrage over the women’s treatment. The women were released, and Wilson urged passage of the suffrage amendment. 75 The Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920 , but Progressives’ hopes that equal political rights would bring democratic equality were not fulfilled. The social justice Progressives split over whether to support the Equal Rights Amendment drawn up by the National Woman’s Party, fearing that it would negate the protective labor legislation they had achieved.

Racialized Progressivism

White Progressives failed to pursue racial equality. Most of them believed the country was not yet ready for such a cultural shift. Some of them believed in theories of racial inferiority. Southern Progressive figure Rebecca Latimer Felton defended racial lynching as a means to protect white women. 76 Other Progressives, such as Sophonisba Breckinridge, fought against racial exclusion policies and promoted interracial cooperation. 77 W. E. B. Du Bois and Addams helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( 1909 ).

African American Progressivism

African Americans believed that Progressive ideology should lead inevitably to racial equality. Du Bois spoke at public forums. 78 He supported the social justice Progressives’ agenda, attending the 1912 Progressive Party convention. Du Bois proposed a racial equality plank for the party platform. Jane Addams helped write the plank. Theodore Roosevelt rejected it, preferring the gradualist policy of Booker T. Washington. Addams objected but mused that perhaps it was not yet time for such a bold move. Racial justice would follow logically from dedication to social justice. 79 Du Bois shifted his support to Woodrow Wilson, while Ida B. Wells-Barnett backed Taft. In 1916 , African American women founded Colored Women’s Hughes clubs to support the Republican nominee. Hughes had reluctantly backed woman suffrage, and African American women viewed suffrage as the means to protect the race. Nannie Helen Burroughs worked through the National Association of Colored Women ( 1896 ) and the National Baptist Convention, demanding suffrage for African American women because they would use it wisely, for the benefit of the race. Burroughs lived in Washington, DC, where she witnessed the segregationist policies of the Wilson administration. She castigated African American men for having voted for him in 1912 . 80 African American Progressives hoped that serving in the military and organizing on the home front during the war would result in equal citizenship when the war ended. Instead, African Americans were subjected to more prejudice and violence. Southern senators blocked the Dyer antilynching bill ( 1922 ).

Immigration Restriction

Anti-immigrant sentiment had been building in the country since passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act ( 1882 ). Several attempts to pass a literacy test bill for immigrants, supported by the Immigration Restriction League ( 1894 ), failed. The forty-one volumes of the Senate-appointed Dillingham Commission ( 1911 ) concluded that immigrants were heavily responsible for the country’s problems and advocated the literacy test. Frances Kellor believed that all immigrants could be Americanized. Randolph Bourne advocated immigration as the path to Americans becoming internationalists. The New Republic , however, feared that excessive immigration would overwhelm an activist state and prevent it from solving social problems. Lillian Wald, Frederic Howe, and other Progressives organized the National Committee for Constructive Immigration Legislation ( 1916 ) hoping to forestall more restrictive measures. In the midst of war fever, Congress passed a literacy test bill over Wilson’s veto ( 1917 ).

100-percent Americanism

Progressives such as Kellor, Wald, and Addams believed that incorporating immigrants into a broad American culture would create a Progressive modern society. Theodore Roosevelt promoted a racialized version of American society. As president, he secured new laws ( 1903 , 1907 ) to exclude certain classes of immigrants—paupers, the insane, prostitutes, and radicals who might pose a threat to American standards of labor—that he deemed incapable of becoming good Americans. He created the Bureau of Immigration to enforce these provisions. The 1907 Immigration Act also stripped citizenship from women who married noncitizens, a situation only reversed in 1922 . At Roosevelt’s behest, Congress tightened requirements for naturalization. Wartime fever and the 1919 Red Scare intensified the search for 100 percent Americanism and undermined the alternative Progressive ideal of a cooperative Americanism. 81

Progressivism beyond the Progressive Era

The democratizing ideals of the Progressive era lived beyond the time period. A regulatory state to eliminate the worst effects of capitalism was created, as most Americans accepted that the federal state had to take on more social responsibility. After ratification of the suffrage amendment, the National American Woman Suffrage Association reconstituted as the National League of Women Voters ( 1920 ) to continue promoting an informed, democratic electorate. The New Deal implemented a substantial social justice Progressive agenda, with the NCL, the Children’s Bureau, and many women who had formed the earlier era’s agenda writing the legislation banning child labor, fostering new labor standards that included minimum wage and maximum hours, and mandating social security for the elderly. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs focused on environmental protection as a democratic right. A women’s joint congressional committee formed to continue pressing for social justice legislation. The National Association of Colored Women joined the committee.

Progressives can be legitimately criticized for not undertaking a more radical restructuring of American society. Some of them can be criticized for believing that they possessed the best vision for a modern, Progressive future. They can be faulted for not promoting racial equality or a new internationalism that might bring about global peace rather than war. Nonetheless, they never intended to undermine capitalism, so they could never truly embrace socialism. In the context of a society that continued to exalt individualism and suspect government interference and working within their own notions of democracy, they accomplished significant changes in American government and society. 82

Discussion of the Literature

The muckraking authors and journalists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries highlighted rapacious capitalism and characterized its wealthy beneficiaries as corrupting the country. In their exposés of the relationship between business and politics, Ida M. Tarbell, Frank Norris, and Upton Sinclair accused politicians of a corrupt bargain in pursuit of their own economic interests against the interests of the people. 83 Drawing upon these investigative writings, early analyses of Progressivism from Benjamin De Witt and Charles and Mary Beard interpreted Progressivism as a dualistic class struggle. On one side were wealthy and privileged special interests seeking to promote themselves at the expense of everyone else. On the other side was a broad public seeking to restore dignity and opportunity to the common people. 84

By the early 1950s, George Mowry and Richard Hofstadter contended that Progressivism was a movement of an older, professional, middle class seeking to reclaim its status, deference, and power, which had been usurped by a new corporate elite and a corrupt political class. 85 In the early 1960s, Samuel Hays argued that rather than being the product of a status revolution, Progressivism was the work of an urban upper class of new and younger leading Republican business and professional men. 86 Robert Wiebe shifted the analysis to describe a broader middle-class Progressivism of new professional men who wished to reorder society by applying bureaucratic and business-oriented skills to political and economic institutions. 87 In Wiebe’s organizational thesis, Progressives were modernizers with a structural-instrumentalist agenda. They rejected reliance on older values and cultural norms to order society and sought to create a modern reordered society with political and economic institutions run by men qualified to apply fiscal expertise, businesslike efficiency, and modern scientific expertise to solve problems and save democracy. 88 The emerging academic disciplines in the social sciences of economics, political economy and political science, and pragmatic education supplied the theoretical bases for this middle-class expert Progressivism. 89 Gabriel Kolko countered such analyses, arguing that Progressivism was a conservative movement promoted by business to protect itself. 90

Professional men and their organizations kept copious records from which scholars could draw this interpretation. By the late 1960s, scholars began to examine the role of other groups in reform movements, ask different questions, and utilize different sources. John Buenker called Progressivism a pluralistic effort, an ethnocultural struggle based on religious values in which urban immigrants and their democratic politicians resisted the old-stock Protestant elites whose Progressive agenda they believed was aimed at homogenizing American culture through policies such as Prohibition and immigration restriction. Ethnic groups were not anti-Progressive but promoted a new Progressive agenda of economic regulation and rights for labor. 91 In the face of conflicting interpretations, Peter Filene questioned whether there indeed was a Progressive movement. Daniel T. Rodgers posited that Progressivism could best be understood as a shift from party politics to interest groups politics. 92

In the last decades of the 20th century, historians began to distance themselves from the very notions of Progressivism. They criticized Progressivism as the ultimate end of a middle-class search for social control of the masses, or they focused on its class dimension. 93 Recent literature has reconsidered the meaning of the Progressive era. Revisiting his early 1980s essay, Daniel T. Rodgers proposed that the big picture of Progressivism was a reaction to the capitalist transformation of society. Robert D. Johnston saw a revived debate concerning the democratic nature of Progressivism and its connections to the present. 94 A recent book by Robyn Muncy takes another look at the emphasis on Progressivism as a social struggle through the biography of Colorado reformer Josephine Roche and her focus on creating social welfare reforms. 95

Primary Sources

There is a wealth of accessible primary source material on Progressives and Progressivism. Many of these documents can now be found through electronic sources such as HathiTrust, Archive.org, and Google Books.

Consult any of the writings of Jane Addams, Louis Brandeis, John R. Commons, Herbert Croly, John Dewey, W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary Parker Follett, Frederic Howe, Florence Kelley, Theodore Roosevelt, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Muckrakers Lincoln Steffens , in The Shame of the Cities (1904) ; Jacob Riis , in How the Other Half Lives: Among the Tenements of New York (1890) ; and Upton Sinclair , in The Jungle (1906) , expose urban political corruption and social conditions. Ida M. Tarbell , in The History of the Standard Oil Company (1904) ; and Frank Norris , in Octopus: A Story of California (1901) , expose business practices. The residents of Hull House published an investigative survey of living conditions in their neighborhood in Hull House Maps and Papers: A Presentation of Nationalities and Wages in a Congested District of Chicago, Together with Comments and Essays on Problems Growing out of Social Conditions ( 1895 ). Useful autobiographies are Tom Johnson , My Story (New York: B. W. Heubsch, 1913) ; Louise DeKoven Bowen , Growing Up with a City (New York: Macmillan, 1926) ; Jane Addams , Twenty Years at Hull House (New York: Macmillan, 1910) ; Ida B. Wells-Barnett , Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida. B. Wells , edited by Alfreda Duster (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970).

Manuscript collections for national and local organizations and individuals include those of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, National Association of Colored Women, Ellen Gates Starr, Women’s City Club of New York, Sophonisba Breckinridge, National Women’s Trade Union League, National Consumers League, and Theodore Roosevelt. Publications of Progressive groups and organizations include Woman Citizen’s Library , Survey , Charities and Commons , New Republic , and National Municipal Review . Investigative reports include the six volumes of the the Pittsburgh Survey ( 1909–1914 ) and Reports of the Immigration Commission (Dillingham Commission), in forty-one volumes ( 1911 ).

Proceedings of organization conferences include those of the National Conferences on City Planning and Congestion, National Conferences on City Planning, International Conference on Women Workers to Promote Peace, and American Federation of Labor. Supreme Court rulings include Ritchie v. People ( 1895 ), Plessy v. Ferguson ( 1896 ), Holden v. Hardy ( 1898 ), Lochner v. New York ( 1905 ), and Muller v. Oregon ( 1908 ).

Links to Digital Materials

Cornell university, ilr school, kheel center.

1911 Triangle Fire .

The History Place

Lewis Hines photos of child labor .

Library of Congress

Child labor collection .

World War I posters .

The National American Woman Suffrage Association .

The National Woman’s Party and protesters .

Theodore Roosevelt .

The Conservation Movement .

University of Illinois Chicago, Special Collections

Settlement houses in Chicago .

Harvard University Library Open Collections Program

Immigration to the United States, 1789‐1930 .

Further Reading

- Connolly, James J. The Triumph of Ethnic Progressivism: Urban Political Culture in Boston, 1900–1925 . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Dawley, Alan . Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Flanagan, Maureen A. Seeing with Their Hearts: Chicago Women and the Vision of the Good City, 1871–1933 . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

- Flanagan, Maureen A. America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s–1920s . New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Greene, Julie . The Canal Builders: Making America’s Empire at the Panama Canal . New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Hofstadter, Richard . The Age of Reform . New York: Vintage Books, 1955.

- Keller, Morton . Regulating a New Economy: Public Policy and Economic Change in America, 1900–1933 . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Knight, Louise W. Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Mattson, Kevin . Creating a Democratic Public: The Struggle for Urban Participatory Democracy During the Progressive Era . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998.

- McGerr, Michael . A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920 . New York: Free Press, 2003.

- Muncy, Robyn . Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890–1935 . New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Muncy, Robyn . Relentless Reformer: Josephine Roche and Progressivism in Twentieth-Century America . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Piott, Steven L. American Reformers, 1870–1920: Progressives in Word and Deed . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Salyer, Lucy . Laws Harsh As Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Schechter, Patricia A. Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880–1930 . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Sklar, Martin J. The Corporate Reconstruction of American Capitalism, 1890–1916 . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Unger, Nancy . Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Wiebe, Robert H. The Search for Order, 1877–1920 . New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

1. Maureen A. Flanagan , America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s–1920s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 10.

2. Jane Addams , Democracy and Social Ethics (New York: Macmillan, 1902).

3. Michael Les Benedict , “Law and Regulation in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era,” in Law as Culture and Culture as Law: Essays in Honor of John Philip Reid , ed. Hendrick Hartog and William E. Nelson (Madison, WI: Madison House Publishers, 2000), 227–263 ; Christopher L. Tomlins , The State and the Unions: Labor Relations, Law, and the Organized Labor Movement in American 1880–1960 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

4. Michael Willrich , City of Courts: Socializing Justice in Progressive Era Chicago (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 100–103.

5. Nancy Woloch , Muller v. Oregon: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford Books, 1996).

6. Victoria Getis , The Juvenile Court and the Progressives (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000).

7. Jennifer Koslow , Cultivating Health: Los Angeles Women and Public Health Reform (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009) ; Daphne Spain , How Women Saved the City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001) ; Anne Firor Scott , Natural Allies: Women’s Associations in American History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992) ; and Judith N. McArthur , Creating the New Woman: The Rise of Southern Women’s Progressive Culture in Texas, 1893–1918 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

8. Nancy C. Unger , Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers: American Women in Environmental History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 86 , for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. See Arthur S. Link and Richard L. McCormick , Progressivism (Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1983), 38 ; Robert H. Wiebe , The Search for Order, 1877–1920 (New York: Hill & Wang, 1967), 191 ; Vincent P. DeSantis, The Shaping of Modern America, 1877–1920 (Arlington Heights, IL: Forum Press), 184; and Daniel Block , “Saving Milk through Masculinity: Public Health Officers and Pure Milk, 1880–1930,” Food and Foodways: History and Culture of Human Nourishment 15 (January–June 2005): 115–135.

9. Kriste Lindenmeyer , “A Right to Childhood”: The U.S. Children’s Bureau and Child Welfare, 1912–46 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997), 10–29 and 114–132.

10. Maureen A. Flanagan , Seeing with Their Hearts: Chicago Women and the Vision of the Good City, 1871–1933 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002) ; and Scott, Natural Allies , 159–174.

11. Robyn Muncy , Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890–1935 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 132–150, 152–154 ; Lindenmeyer, “A Right to Childhood,” chap. 4, esp. 100–103; and Lynne Curry , Modern Mothers in the Heartland: Gender, Health, and Progress in Illinois, 1900–1930 (Columbus: Ohio State University, 1999), 120–131.

12. Scott, Natural Allies , 147

13. Landon R. Y. Storrs , Civilizing Capitalism: The National Consumers’ League, Women’s Activism, and Labor Standards in the New Deal (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), chap. 1.

14. Elizabeth Payne , Reform, Labor, and Feminism: Margaret Dreier Robins and the Women’s Trade Union League (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

15. Kevin Mattson , Creating a Democratic Public: The Struggle for Urban Participatory Democracy During the Progressive Era (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998), 45.

16. Mattson, Creating a Democratic Public , includes a chapter on Follett, but the rest of the book focuses on men. Alan Dawley , Struggles for Justice: Social Responsibility and the Liberal State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991), 102 , shortchanges women’s Progressivism, saying it “merely extended the boundaries of women’s sphere to the realm of ‘social housekeeping’”; Daniel T. Rodgers , Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 19–20, 239–240 , calls them “social maternalists” rather than social justice Progressives and claims that they were motivated by “sentiment” and focused on protecting “women’s weakness.” For Chicago women’s clubs, see Elizabeth Belanger , “The Neighborhood Ideal: Local Planning-Practices in Progressive-Era Women’s Clubs,” Journal of Planning History 8.2 (May 2009): 87–110.

17. Nancy Unger , Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) . Charles McCarthy , The Wisconsin Idea (New York: Macmillan, 1912).

18. Robert D. Johnston , The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 123.

19. Martin J. Schiesl , The Politics of Efficiency: Municipal Administration and Reform in American, 1880–1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997) , provides the clearest overall picture of these elements of this political Progressivism.

20. Committee on Municipal Program of the National Municipal League , A Model City Charter and Municipal Home Rule (Philadelphia: National Municipal League, 1916).

21. Amy Bridges , Morning Glories: Municipal Reform in the Southwest (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999) ; Bradley R. Rice , “The Galveston Plan of City Government by Commission: The Birth of a Progressive Idea,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly , 78.4 (April 1975): 365–408 ; and Schiesl, The Politics of Efficiency , 136–137 for Des Moines.

22. Kenneth Finegold , Experts and Politicians: Reform Challenges to Machine Politics in New York, Cleveland, and Chicago (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), 82–88 for Johnson and 107–111 for charter reform in Cleveland.

23. Maureen A. Flanagan , Charter Reform in Chicago (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University, 1987).

24. James J. Connolly , The Triumph of Ethnic Progressivism: Urban Political Culture in Boston, 1900–1925 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 106–107.

25. David Stradling , Smokestacks and Progressives: Environmentalists, Engineers, and Air Quality in America, 1881–1951 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 21–36.

26. Angela Gugliotta , “How, When, and for Whom Was Smoke a Problem?” in Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and Its Region , ed. Joel Tarr (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 118–120.

27. Stradling, Smokestacks and Progressives , 63–67 and 108–137, provides a comprehensive overview of the political Progressivism of smoke pollution.

28. Angela Gugliotta , “Class, Gender, and Coal Smoke: Gender Ideology and Environmental Injustice in Pittsburgh, 1868–1914,” Environmental History 6.2 (April 2000): 173–176.

29. Flanagan, Seeing with Their Hearts , 100–102 and America Reformed , 173–179. See Scott, Natural Allies , 143–145 for more on women’s health protective associations.

30. Anne-Marie Szymanski , “Regulatory Transformations in a Changing City: The Anti-Smoke Movement in Baltimore, 1895–1931,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 13.3 (July 2014): 364–366.

31. William H. Wilson , The City Beautiful Movement (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985) ; and Jon A. Peterson , The Birth of City Planning in the United States, 1840–1917 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003) , Parts 2 and 3.

32. Carl A. Smith , The Plan of Chicago: Daniel Burnham and the Remaking of the American City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

33. Max Page , The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999) ; and Mel Scott , American City Planning since 1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971) , Parts 2, 3, and 4.

34. Eric Sandweiss , St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

35. Susan Marie Wirka , “The City Social Movement: Progressive Women Reformers and Early Social Planning,” in Planning the Twentieth-Century American City , ed. Mary Corbin Sies and Christopher Silver (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 55–75 ; and Maureen A. Flanagan , “City Profitable, City Livable: Environmental Policy, Gender, and Power in Chicago in the 1910s,” Journal of Urban History 22.2 (January 1996): 163–190.

36. Frederic Howe , The City: The Hope of Democracy (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1905).

37. Mary Parker Follett , The New State: Group Organization the Solution of Popular Government (New York: Longmans, Green, 1918).

38. Connolly, The Triumph of Ethnic Progressivism.

39. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings , 236–238, 251–254.

40. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings , 108–109.

41. Dorothy Ross , The Origins of American Social Science (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 158–159.

42. Ellen Fitzpatrick , Endless Crusade: Women Social Scientists and Progressive Reform (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

43. Theda Skocpol , Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 183.

44. Fitzpatrick, Endless Crusade , 40–44, 80, 82, and 90–91.

45. Martin J. Sklar , The Corporate Reconstruction of American Capitalism, 1890–1916 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

46. Samuel P. Hays , Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Movement, 1890–1920 (repr., New York: Atheneum, 1969), chap. 7.

47. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency , chap. 8.

48. DeSantis, The Shaping of Modern America , 194–199.

49. Eric Rauchway , Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt’s America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2003), 189–200.

50. Morton Keller , Regulating a New Society: Public Policy and Social Change in America, 1900–1930 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 194–196.

51. Julie Greene , Pure and Simple Politics: The American Federation of Labor and Political Activism, 1881–1917 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 219, 279 ; and Shelton Stromquist, Reinventing the “People”: The Progressive Movement, the Class Problem, and the Origins of Modern Liberalism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 66.

52. Greene, Pure and Simple Politics , 9, 235.

53. Fr. John Ryan , The Living Wage: Its Ethical and Economic Aspects (New York: Macmillan, 1906), 283–285 . Richard Ely wrote the book’s introduction.

54. Payne, Reform, Labor, and Feminism , 95–107.

55. Shelton Stromquist , “The Crucible of Class: Cleveland Politics and the Origins of Municipal Reform in the Progressive Era,” Journal of Urban History 23.2 (January 1997): 192–220.

56. Daniel J. Johnson , “‘No Make-Believe Class Struggle’: The Socialist Municipal Campaign in Los Angeles, 1922,” Labor History 41.1 (February 2000): 25–45 ; Douglas E. Booth , “Municipal Socialism and City Government Reform: The Milwaukee Experience, 1910–1940,” Journal of Urban History 12.1 (November 1985): 51–71 ; and Josephine Kaneko , “What a Socialist Alderman Would Do,” Coming Nation (March 1914).

57. Gail Radford , “From Municipal Socialism to Public Authorities: Institutional Factors in the Shaping of American Public Enterprise,” Journal of American History 90.3 (December 2003): 863–890.

58. Nell Irvin Painter , Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 150.

59. Herbert Croly , The Promise of American Life (New York: Macmillan, 1909).

60. Emily Rosenberg , Financial Missionaries to the World: The Politics and Culture of Dollar Diplomacy, 1900–1930 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

61. Matthew Frye Jacobson , Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876–1917 (New York: Hill & Wang, 2000), 227.

62. Alan Dawley , Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 81.

63. Theodore Roosevelt , The Strenuous Life: Essays and Addresses (New York: Century, 1903).

64. George F. Becker , “Conditions Requisite to Our Success in the Philippine Islands,” address to the American Geographical Society, February 20, 1901, Bulletin of the American Geographical Society (1901): 112–123.

65. Albert Beveridge , The Young Man and the World (New York: Appleton, 1905), 338 ; and Kristen Hoganson , Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998).

66. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings , is the most complete analysis of this internationalism.

67. Jane Addams , Newer Ideals of Peace (New York: Macmillan, 1907) ; Robert La Follette , LaFollette’s Weekly 5.1 (March 29, 1913) ; Kristen Hoganson , “‘As Badly-Off As the Filipinos’: U.S. Women Suffragists and the Imperial Issue at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Journal of Women’s History 13.2 (Summer 2001): 9–33 ; and Nancy C. Unger , Belle La Follette: Progressive Era Reformer (New York: Routledge, 2015).

68. David Kennedy , Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980).

69. Harriet Hyman , introduction to Women at The Hague , by Jane Addams , Emily Greene Balch , and Alice Hamilton (repr., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003) ; and Kathryn Kish Sklar , “‘Some of Us Who Deal with the Social Fabric’: Jane Addams Blends Peace and Social Justice,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 2.1 (January 2003): 80–96.

70. Julia F. Irwin , Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

71. Jane Addams , Peace and Bread in Time of War (New York: Macmillan, 1922), 4–5.

72. Unger, Fighting Bob La Follette , chap. 14.

73. Kennedy, Over Here , 34; New Republic 10 (February 10 and 17, 1917); and Dawley, Changing the World , 122, 147, 165–169.

74. Walter Lippmann , “The World Conflict in Relation to American Democracy,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 72 (July 1917): 1–10 ; Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings , 283–285, 288–289; and Dawley, Changing the World , 147.

75. Christine Lunardini , From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910–1928 (New York: New York University Press, 1986).

76. LeeAnn Whites , “Love, Hate, Rape, and Lynching: Rebecca Latimer Fulton and the Gender Politics of Racial Violence,” in Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy , ed. David Cecelski and Timothy B. Tyron (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

77. Fitzpatrick, Endless Crusade , 180–181.

78. Mattson, Creating a Democratic Public , 44.

79. David Levering Lewis , W. E. B. DuBois: A Biography, 1868–1963 (New York: Henry Holt, 2009), 276–277 ; and Gary Gerstle , American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 77–78 , for Addams.

80. Lisa G. Masterson , Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877–1932 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 101–106.

81. John Higham , Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1869–1925 (1955; repr. New York: Atheneum, 1974), 129–130, 222–224 ; and Gerstle, American Crucible , 55–56.

82. Robert D. Johnston , “Long Live Teddy/Death to Woodrow: The Polarized Politics of the Progressive Era in the 2012 Election,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 13.3 (July 2014): 411–443.

83. Ida M. Tarbell , The History of the Standard Oil Company (New York: McClure, Phillips, 1904) ; Frank Norris , The Octopus: A Story of California (New York: Doubleday, 1901) ; and Upton Sinclair , The Jungle (New York: Jungle Publishing, 1906).

84. Benjamin De Witt , The Progressive Movement (New York: Macmillan, 1915) ; and Charles A. Beard and Mary R. Beard , The Rise of American Civilization (New York: Macmillan, 1927).

85. George E. Mowry , The California Progressives (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951) ; and Richard Hofstadter , The Age of Reform (New York: Vintage Books, 1955).

86. Samuel P. Hays , “The Politics of Reform in Municipal Government in the Progressive Era,” Pacific Historical Review 55.4 (October 1964): 157–159.

87. Robert H. Wiebe , Businessmen and Reform: A Study of the Progressive Movement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962) ; and Wiebe, The Search for Order .

88. Schiesl, The Politics of Efficiency ; and Finegold, Experts and Politicians.

89. John Louis Recchiuti , Social Science and Progressive Era Reform in New York City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007) ; and Dorothy Ross, The Origins of American Social Science .

90. Gabriel Kolko , The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900–1916 (New York: Free Press, 1963).

91. John D. Buenker , Urban Liberalism and Progressive Reform (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1973).

92. Peter G. Filene , “An Obituary for the Progressive Movement,” American Quarterly 22.1 (Spring 1970): 20–34 ; and Daniel T. Rodgers , “In Search of Progressivism,” Reviews in American History 10.4 (December 1982): 113–132.

93. Paul Boyer , Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978) ; Michael McGerr , A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920 (New York: Free Press, 2003) ; and Jackson Lears , Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877–1920 (New York: Harper, 2009).

94. Daniel T. Rodgers , “Capitalism and Politics in the Progressive Era and in Ours,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 13.3 (July 2014): 379–386 ; Robert D. Johnston, “Long Live Teddy/Death to Woodrow, 411–443; and Stromquist, Reinventing the “People.”

95. Robyn Muncy , Relentless Reformer: Josephine Roche and Progressivism in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Related Articles

- Struggles over Individual Rights and State Power in the Progressive Era

- Anti-Imperialism

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, American History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: null; date: 14 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

Dr. Della Perez

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Perennialism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Perennialism?

- What do Perrenialists believe are the primary goals of schooling?

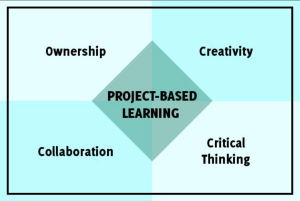

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find. As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author?

Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.