- The Big Story

- Cyber Monday

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

.png?format=original)

Bill Gates: Here's My Plan to Improve Our World -- And How You Can Help

But like anyone with a mild obsession, I think mine is entirely justified. Two out of every five people on Earth today owe their lives to the higher crop outputs that fertilizer has made possible. It helped fuel the Green Revolution, an explosion of agricultural productivity that lifted hundreds of millions of people around the world out of poverty.

These days I get to spend a lot of time trying to advance innovation that improves people's lives in the same way that fertilizer did. Let me reiterate this: A full 40 percent of Earth's population is alive today because, in 1909, a German chemist named Fritz Haber figured out how to make synthetic ammonia. Another example: Polio cases are down more than 99 percent in the past 25 years, not because the disease is going away on its own but because Albert Sabin and Jonas Salk invented polio vaccines and the world rolled out a massive effort to deliver them.

Thanks to inventions like these, life has steadily gotten better. It can be easy to conclude otherwise—as I write this essay, more than 100,000 people have died in a civil war in Syria, and big problems like climate change are bearing down on us with no simple solution in sight. But if you take the long view, by almost any measure of progress we are living in history's greatest era. Wars are becoming less frequent. Life expectancy has more than doubled in the past century. More children than ever are going to primary school. The world is better than it has ever been.

But it is still not as good as we wish. If we want to accelerate progress, we need to actively pursue the same kind of breakthroughs achieved by Haber, Sabin, and Salk. It's a simple fact: Innovation makes the world better—and more innovation equals faster progress. That belief drives the work my wife, Melinda, and I are doing through our foundation.

We went on a Safari to see wild animals but ended up getting our first sustained look at extreme poverty. We were shocked.

Of course, not all innovation is the same. We want to give our wealth back to society in a way that has the most impact, and so we look for opportunities to invest for the largest returns. That means tackling the world's biggest problems and funding the most likely solutions. That's an even greater challenge than it sounds. I don't have a magic formula for prioritizing the world's problems. You could make a good case for poverty, disease, hunger, war, poor education, bad governance, political instability, weak trade, or mistreatment of women. Melinda and I have focused on poverty and disease globally, and on education in the US. We picked those issues by starting with an idea we learned from our parents: Everyone's life has equal value. If you begin with that premise, you quickly see where the world acts as though some lives aren't worth as much as others. That's where you can make the greatest difference, where every dollar you spend is liable to have the greatest impact.

I have known since my early thirties that I was going to give my wealth back to society. The success of Microsoft provided me with an enormous fortune, and I felt responsible for using it in a thoughtful way. I had read a lot about how governments underinvest in basic scientific research. I thought, that's a big mistake. If we don't give scientists the room to deepen our fundamental understanding of the world, we won't provide a basis for the next generation of innovations. I figured, therefore, that I could help the most by creating an institute where the best minds would come to do research.

There's no single lightbulb moment when I changed my mind about that, but I tend to trace it back to a trip Melinda and I took to Africa in 1993. We went on a safari to see wild animals but ended up getting our first sustained look at extreme poverty. I remember peering out a car window at a long line of women walking down the road with big jerricans of water on their heads. How far away do these women live? we wondered. Who's watching their children while they're away?

That was the beginning of our education in the problems of the world's poorest people. In 1996 my father sent us a New York Times article about the million children who were dying every year from rotavirus, a disease that doesn't kill kids in rich countries. A friend gave me a copy of a World Development Report from the World Bank that spelled out in detail the problems with childhood diseases.

Melinda and I were shocked that more wasn't being done. Although rich-world governments were quietly giving aid, few foundations were doing much. Corporations weren't working on vaccines or drugs for diseases that affected primarily the poor. Newspapers didn't write a lot about these children's deaths.

This realization led me to rethink some of my assumptions about how the world improves. I am a devout fan of capitalism. It is the best system ever devised for making self-interest serve the wider interest. This system is responsible for many of the great advances that have improved the lives of billions—from airplanes to air-conditioning to computers.

But capitalism alone can't address the needs of the very poor. This means market-driven innovation can actually widen the gap between rich and poor. I saw firsthand just how wide that gap was when I visited a slum in Durban, South Africa, in 2009. Seeing the open-pit latrine there was a humbling reminder of just how much I take modern plumbing for granted. Meanwhile, 2.5 billion people worldwide don't have access to proper sanitation, a problem that contributes to the deaths of 1.5 million children a year.

Governments don't do enough to drive innovation either. Although aid from the rich world saves a lot of lives, governments habitually underinvest in research and development, especially for the poor. For one thing, they're averse to risk, given the eagerness of political opponents to exploit failures, so they have a hard time giving money to a bunch of innovators with the knowledge that many of them will fail.

By the late 1990s, I had dropped the idea of starting an institute for basic research. Instead I began seeking out other areas where business and government underinvest. Together Melinda and I found a few areas that cried out for philanthropy—in particular for what I have called catalytic philanthropy.

I have been sharing my idea of catalytic philanthropy for a while now. It works a lot like the private markets: You invest for big returns. But there's a big difference. In philanthropy, the investor doesn't need to get any of the benefit. We take a double-pronged approach: (1) Narrow the gap so that advances for the rich world reach the poor world faster, and (2) turn more of the world's IQ toward devising solutions to problems that only people in the poor world face. Of course, this comes with its own challenges. You're working in a global economy worth tens of trillions of dollars, so any philanthropic effort is relatively small. If you want to have a big impact, you need a leverage point—a way to put in a dollar of funding or an hour of effort and benefit society by a hundred or a thousand times as much.

One way you can find that leverage point is to look for a problem that markets and governments aren't paying much attention to. That's what Melinda and I did when we saw how little notice global health got in the mid-1990s. Children were dying of measles for lack of a vaccine that cost less than 25 cents, which meant there was a big opportunity to save a lot of lives relatively cheaply. The same was true of malaria. When we made our first big grant for malaria research, it nearly doubled the amount of money spent on the disease worldwide—not because our grant was so big, but because malaria research was so underfunded.

But you don't necessarily need to find a problem that's been missed. You can also discover a strategy that has been overlooked. Take our foundation's work in education. Government spends huge sums on schools. The state of California alone budgets roughly $68 billion annually for K-12, more than 100 times what our foundation spends in the entire United States. How could we have an impact on an area where the government spends so much?

We looked for a new approach. To me one of the great tragedies of our education system is that teachers get so little help identifying and learning from those who are most effective. As we talked with instructors about what they needed, it became clear that a smart application of technology could make a big difference. Teachers should be able to watch videos of the best educators in action. And if they want, they should be able to record themselves in the classroom and then review the video with a coach. This was an approach that others had missed. So now we're working with teachers and several school districts around the country to set up systems that give teachers the feedback and support they deserve.

The goal in much of what we do is to provide seed funding for various ideas. Some will fail. We fill a function that government cannot—making a lot of risky bets with the expectation that at least a few of them will succeed. At that point, governments and other backers can help scale up the successful ones, a much more comfortable role for them.

We work to draw in not just governments but also businesses, because that's where most innovation comes from. I've heard some people describe the economy of the future as "post-corporatist and post-capitalist"—one in which large corporations crumble and all innovation happens from the bottom up. What nonsense. People who say things like that never have a convincing explanation for who will make drugs or low-cost carbon-free energy. Catalytic philanthropy doesn't replace businesses. It helps more of their innovations benefit the poor.

Look at what happened to agriculture in the 20th century. For decades, scientists worked to develop hardier crops. But those advances mostly benefited the rich world, leaving the poor behind. Then in the middle of the century, the Rockefeller and Ford foundations stepped in. They funded Norman Borlaug's research on new strains of high-yielding wheat, which sparked the Green Revolution. (As Borlaug said, fertilizer was the fuel that powered the forward thrust of the Green Revolution, but these new crops were the catalysts that sparked it.) No private company had any interest in funding Borlaug. There was no profit in it. But today all the people who have escaped poverty represent a huge market opportunity—and now companies are flocking to serve them.

Or take a more recent example: the advent of Big Data. It's indisputable that the availability of massive amounts of information will revolutionize US health care, manufacturing, retail, and more. But it can also benefit the poorest 2 billion. Right now researchers are using satellite images to study soil health and help poor farmers plan their harvests more efficiently. We need a lot more of this kind of innovation. Otherwise, Big Data will be a big wasted opportunity to reduce inequity.

People often ask me, "What can I do? How can I help?"

Rich-world governments need to maintain or even increase foreign aid, which has saved millions of lives and helped many more people lift themselves out of poverty. It helps when policymakers hear from voters, especially in tough economic times, when they're looking for ways to cut budgets. I hope people let their representatives know that aid works and that they care about saving lives. Bono's group ONE.org is a great channel for getting your voice heard.

Companies—especially those in the technology sector—can dedicate a percentage of their top innovators' time to issues that could help people who've been left out of the global economy or deprived of opportunity here in the US. If you write great code or are an expert in genomics or know how to develop new seeds, I'd encourage you to learn more about the problems of the poorest and see how you can help.

At heart I'm an optimist. Technology is helping us overcome our biggest challenges. Just as important, it's also bringing the world closer together. Today we can sit at our desks and see people thousands of miles away in real time. I think this helps explain the growing interest young people today have in global health and poverty. It's getting harder and harder for those of us in the rich world to ignore poverty and suffering, even if it's happening half a planet away.

Technology is unlocking the innate compassion we have for our fellow human beings. In the end, that combination—the advances of science together with our emerging global conscience—may be the most powerful tool we have for improving the world.

Think Globally, Act Massively

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation focuses on catalytic philanthropy—investments that can yield massive returns. That means finding areas where governments and private businesses aren’t innovating. Here are some of the foundation’s major activities over the past 15 years.

Pledged $750 million to help set up the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (now the GAVI Alliance), supported by leading members of the world health community and experts in international childhood diseases.

Gave $50 million to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative.

Launched the Gates Millennium Scholars program to provide 1,000 low-income and minority students a year with scholarships and support for select advanced degrees at any college or university.

Officially established the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with a focus on health, education, and libraries.

Pledged $100 million to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria—the first of $1.4 billion in commitments to an organization that has helped save more than 9 million lives.

Announced the Grand Challenges in Global Health initiative to fund research that promises to greatly advance work against diseases that disproportionately affect people in the developing world.

Created Agricultural Development, beginning with a $150 million joint investment with the Rockefeller Foundation, to establish the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, which helps lift poor farmers out of poverty.

Launched the Measures of Effective Teaching Project with 3,000 participating teachers to create better feedback and development systems for educators.

Called on the global health community to declare this the Decade of Vaccines, with the goal of saving more than 20 million lives by 2020; pledged $10 billion to help develop and deliver vaccines.

Launched the Next Generation Learning Challenges to push innovation that promotes personalized student learning.

Hosted the GAVI Alliance pledging conference, which raised $4.3 billion from governments, philanthropists, and the private sector to help immunize nearly 250 million of the world’s poorest children by 2015.

Offered a $42 million reward for the invention of a toilet that can provide safe, affordable sanitation to the developing world while processing the waste into reusable energy, fertilizer, and fresh water.

Joined 13 pharmaceutical companies, the US, UK, and UAE governments, the World Bank, and various global health organizations in a coordinated push to eliminate or control 10 neglected tropical diseases by the end of 2020.

Melinda Gates chaired the Landmark London Summit on Family Planning, which united global leaders to provide 120 million women in the world’s poorest countries with access to contraceptives by 2020.

Supported a six-year, $5.5 billion effort to eradicate polio by 2018.

When more teachers have the tools they need to reach their students and teach math in a way that resonates, I’m confident that more of their students will graduate with a love of math just like mine.

Our 2021 Annual Letter

The world has an important opportunity to turn the hard-won lessons of this pandemic into a healthier, more equal future for all.

We are writing this letter after a year unlike any other in our lifetimes.

Two decades ago, we created a foundation focused on global health because we wanted to use the returns from Microsoft to improve as many lives as possible. Health is the bedrock of any thriving society. If your health is compromised—or if you’re worried about catching a deadly disease—it’s hard to concentrate on anything else. Staying alive and well becomes your priority to the necessary detriment of everything else.

Over the last year, many of us have experienced that reality ourselves for the first time. Almost every decision now comes with a new calculus: How do you minimize your risk of contracting or spreading COVID-19? There are probably some epidemiologists reading this letter, but for most people, we’re guessing that the past year has forced you to reorient your lives around an entirely new vocabulary—one that includes terms like “social distancing” and “flattening the curve” and the “R0” of a virus. (And for the epidemiologists reading this, we bet no one is more surprised than you that we now live in a world where your colleague Anthony Fauci has graced the cover of InStyle magazine.)

When we wrote our last Annual Letter , the world was just starting to understand how serious a novel coronavirus pandemic could get. Even though our foundation had been concerned about a pandemic scenario for a long time—especially after the Ebola epidemic in West Africa—we were shocked by how drastically COVID-19 has disrupted economies, jobs, education, and well-being around the world.

Only a few weeks after we first heard the word “COVID-19,” we were closing our foundation’s offices and joining billions of people worldwide in adjusting to radically different ways of living. For us, the days became a blur of video meetings, troubling news alerts, and microwaved meals.

But the adjustments the two of us have made are nothing compared to the impact the pandemic has had on others. COVID-19 has cost lives, sickened millions, and thrust the global economy into a devastating recession. One and a half billion children lost time in the classroom, and some may never return. Essential workers are doing impossible jobs at tremendous risk to themselves and their families. Stress and isolation have triggered far-reaching impacts on mental health. And families in every country have had to miss out on so many of life’s most important moments—graduations, weddings, even funerals. (When Bill Sr. died last September, it was made even more painful by the fact we couldn’t all come together to mourn.)

History will probably remember these last couple of months as the most painful point of the entire pandemic. But hope is on the horizon. Although we have a long recovery in front of us, the world has achieved some significant victories against the virus in the form of new tests, treatments, and vaccines. We believe these new tools will soon begin bending the curve in a big way.

The moment we now find ourselves in calls to mind a quote from Winston Churchill. In the fall of 1942, he gave a famous speech marking a military victory that he believed would be a turning point in the war against Nazi Germany. “This is not the end,” he warned. “It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

When it comes to COVID-19, we are optimistic that the end of the beginning is near. We are also realistic about what it’s taken to get here: the largest public health effort in the history of the world—one involving policymakers, researchers, healthcare workers, business leaders, grassroots organizers, religious communities, and so many others working together in new ways.

That kind of shared effort is important, because in a global crisis like this one, you don’t want companies making decisions driven by a profit motive or governments acting with the narrow goal of protecting only their own citizens. You need a lot of different people and interests coming together in goodwill to benefit all of humanity.

Philanthropy can help facilitate that cooperation. Because our foundation has been working on infectious diseases for decades, we have strong, long-standing relationships with the World Health Organization, experts, governments, and the private sector. And because our foundation is specifically focused on the challenges facing the world’s poorest people, we also understand the importance of ensuring that the world is considering the unique needs of low-income countries, too.

To date, our foundation has invested $1.75 billion in the fight against COVID-19. Most of that funding has gone toward producing and procuring crucial medical supplies. For example, we backed researchers developing new COVID-19 treatments including monoclonal antibodies, and we worked with partners to ensure that these drugs are formulated in a way that’s easy to transport and use in the poorest parts of the world so they benefit people everywhere.

We’ve also supported efforts to find and distribute safe and effective vaccines against the virus. Over the last two decades, our resources backed the development of 11 vaccines that have been certified as safe and effective, and our partners have been applying the lessons we learned along the way to the development of vaccines against COVID-19.

It’s possible that by the time you read this, you or someone you know may have already received a COVID-19 vaccine. The fact that these vaccines are already becoming available is, we think, pretty remarkable—especially considering that COVID-19 was a virtually unknown pathogen at the beginning of 2020 and how rigorous the process is for proving a vaccine’s safety and efficacy. (It’s important that people understand that even though these vaccines were developed on an expedited timeline, they still had to meet strict guidelines before being approved.)

A resident of a nursing home in New York City receives a COVID-19 vaccine. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

No one country or company could have achieved this alone. Funders around the world pooled resources, competitors shared research findings, and everyone involved had a head start thanks to many years of global investment in technologies that have helped unlock a new era in vaccine development. If the novel coronavirus had emerged in 2009 instead of 2019, the road to a vaccine would have been much longer.

Of course, creating safe and effective vaccines in a laboratory is only the beginning of the story. Because the world needs billions of doses in order to protect everyone threatened by this disease, we helped partners figure out how to manufacture vaccines at the same time as they were being developed (a process that usually happens sequentially).

Now, the world has to get those doses out to everyone who needs them—starting with frontline health workers and other high-risk groups. Our foundation has worked with manufacturers and partners to deliver other vaccines cheaply and on a very large scale in the past (including to 822 million kids in low-income countries through Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance), and we’re doing the same with COVID-19.

Our foundation and its partners have pivoted to meet the challenges of COVID-19 in other ways as well. When our friend Warren Buffett donated the bulk of his fortune to double our foundation’s resources in 2006, he urged us to stay focused on the issues that have always been central to our mission. Tackling COVID-19 was an essential part of any global health work in 2020, but it hasn’t been our sole focus over the last year. Our colleagues continue to make progress across all of our program areas.

The malaria team has had to rethink how to distribute bed nets in a time when it’s no longer safe to hold an event to give them to a lot of people at once. We’re helping partners understand COVID-19’s impact on pregnant women and babies and making sure that they continue to receive essential health services. Our education partners are helping teachers adjust to a world where their laptop is their classroom. In other words, we remain trained on the same goal we’ve had since our foundation opened its doors: making sure every single person on the planet has the chance to live a healthy and productive life.

A high school teacher in Seoul, Korea, works with her students remotely. (Chung Sung-Jung/Getty Images)

Health workers deliver mosquito nets in Benin. (Yanick Folly/Getty Images)

A healthcare worker wearing personal protective equipment helps a pregnant woman in labor in Ankara, Turkey. (Ozge Elif Kizil/Getty Images)

A young woman talks about contraception at a community center in Nairobi, Kenya. (Alissa Everett/Getty Images)

If there’s a reason we’re optimistic about life on the other side of the pandemic, it’s this: While the pandemic has forced many people to learn a new vocabulary, it’s also brought new meaning to old terms like “global health.”

In the past, “global health” was rarely used to mean the health of everyone, everywhere. In practice, people in rich countries used this term to refer to the health of people in non-rich countries. A more accurate term probably would have been “developing country health.”

This past year, though, that changed. In 2020, global health went local. The artificial distinctions between rich countries and poor countries collapsed in the face of a virus that had no regard for borders or geography.

We all saw firsthand how quickly a disease you’ve never heard of in a place you may have never been can become a public health emergency right in your own backyard. Viruses like COVID-19 remind us that, for all our differences, everyone in this world is connected biologically by a microscopic network of germs and particles—and that, like it or not, we’re all in this together.

We hope the experience we’ve all lived through over the last year will lead to a long-term change in the way people think about global health—and help people in rich countries see that investments in global health benefit not only low-income countries but everyone. We were thrilled to see the United States include $4 billion for Gavi in its latest COVID-19 relief package. Investments like these will put all of us in a better position to defeat the next set of global challenges.

Just as World War II was the defining event for our parents’ generation, the coronavirus pandemic we are living through right now will define ours. And just as World War II led to greater cooperation between countries to protect the peace and prioritize the common good, we think that the world has an important opportunity to turn the hard-won lessons of this pandemic into a healthier, more equal future for all.

In the rest of this letter, we write about two areas we see as essential to building that better future: prioritizing equity and getting ready for the next pandemic.

Can we emerge from this pandemic more equal than we entered it?

Melinda: One of the things I’ve missed most over the last year is traveling to see our foundation’s work in action. I have photos all over our house of the women I’ve met on these trips. Now that I’m working from home, I see their faces all the time.

I often wonder what the pandemic looks like through their eyes and how they’re coping. When I’m on videocalls with experts and world leaders, I try to imagine how the decisions being made in these conversations will affect these women and their families. They’re a daily reminder of the importance of ensuring that the world’s COVID-19 response leaves no one behind.

From AIDS to Zika to Ebola, disease outbreaks tend to follow a grim pattern. They hurt some people more than others—and who they hurt most is not random. As they infect societies, they exploit pre-existing inequalities.

The same is true of COVID-19. People with less are faring worse than those with more. Essential workers are facing greater risks than those who can work from home. Students without internet access are falling behind students who are learning remotely. In the United States, communities of color are more likely to get sick and die than other Americans. And all around the world, women who have been fighting for power and influence over their lives are seeing decades of fragile progress shattered in a matter of months.

From the beginning of the pandemic, our foundation has worked with partners in the United States and around the world to address the uneven social and economic impacts of COVID-19 and keep those pre-existing inequalities from growing deeper.

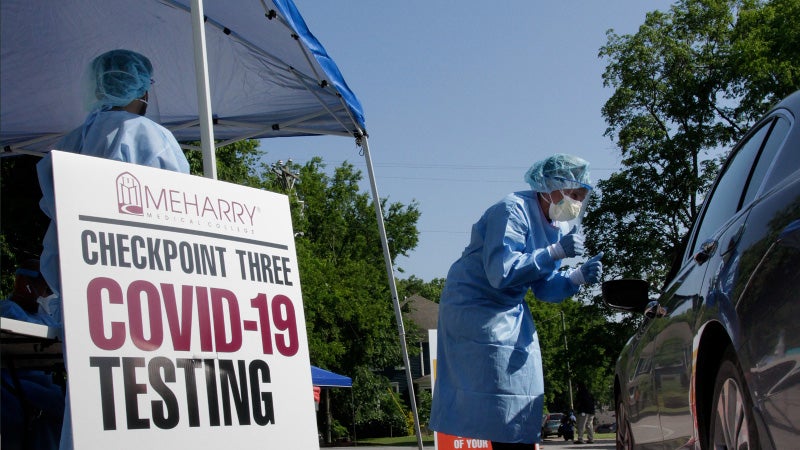

In the United States, many of our anti-COVID efforts overlap with our work on racial equity. For example, the data tell us that Black Americans are three times as likely as white Americans to get COVID-19, and they are also more likely to live in an area with limited access to COVID-19 testing. To help meet the demand for local community testing, our foundation partnered with historically Black colleges and universities to expand diagnostic testing capacity on their campuses.

Healthcare workers test people for COVID-19 in Nashville, Tennessee. (Meharry Medical College)

We’re also addressing the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on people of color in other ways, including through our foundation’s U.S. education work. We’re concerned about students falling behind at all levels (when schools closed last spring, the average student lost months of learning), but we’re especially troubled that COVID-19 could exacerbate long-standing barriers to higher education, particularly for students who are Black, Latino, or from low-income households. Median lifetime earnings of college graduates are twice those of high school graduates, so the stakes for these young people are high. To help students navigate COVID-19 roadblocks, our foundation expanded our partnerships with three organizations that have a proven track record of using digital tools to help students stay on the path to a college degree. We think the models and approaches these organizations are honing now will continue to expand opportunities for students post-pandemic, too.

When it comes to our work outside the United States, my major focus has been calling on world leaders to put women at the center of their COVID-19 response. If governments ignore the fact that the pandemic and resulting recession are affecting women differently, it will prolong the crisis and slow economic recovery for everyone.

For example, because of the economic shutdowns over the last year, hundreds of millions of people in low-income countries have needed help from their government to meet basic needs. But the cruel irony is that the women who most need these economic lifelines tend to be invisible to their governments. It’s hard to send cash safely and swiftly to a woman who doesn’t appear in the tax rolls, have a formal identification, or own a mobile phone. Unless financial systems are specifically designed to include these women, these systems are likely to exclude them, pushing them even further to the economic margins. Our foundation has worked with the World Bank to help countries overcome these hurdles and create digital cash transfer programs with women’s needs in mind.

A business correspondent agent helps a woman with a bank transaction in Silana, India.

More broadly, we’re supporting efforts to design economic response plans targeted at women and low-wage workers. In low- and middle-income countries, the poorest people tend to be self-employed in the informal sector—as farmers or street vendors, for example. Policymakers often overlook these workers, and traditional stimulus measures don’t meet their needs. (Tax rebates don’t really help people who don’t pay taxes—and who pays for your paid leave if you work for yourself?) Our foundation helped fund research into how governments can repair these holes in the safety net by prioritizing measures like cash grants, food relief, and moratoriums on rent and utilities.

This past year has also shined a spotlight on women’s unpaid labor , an issue I’ve written about in this letter before. With billions of people now staying home, the demand for unpaid care work—cooking, cleaning, and childcare—has surged. Women already did about three-quarters of that work. Now, in the pandemic, they’ve taken on even more of it. This work may be unpaid, but it comes at an enormous cost: Globally, a two-hour increase in women’s unpaid care work is correlated with a 10 percentage point decrease in women’s labor force participation. As governments rebuild their economies, it’s time to start treating child care as essential infrastructure—just as worthy of funding as roads and fiber optic cables. In the long term, this will help create more productive and inclusive post-pandemic economies.

Bill and I are deeply concerned, though, that in addition to shining a light on so many old injustices, the pandemic will unleash a new one: immunity inequality , a future where the wealthiest people have access to a COVID-19 vaccine, while the rest of the world doesn’t.

Already, wealthy nations have spent months prepurchasing doses of vaccine to start immunizing their people the moment those vaccines are approved. But as things stand now, low- and middle-income countries will only be able to cover about one out of five people who live there over the next year. In a world where global health is local, that should concern all of us.

From the beginning of the pandemic, we have urged wealthy nations to remember that COVID-19 anywhere is a threat everywhere. Until vaccines reach everyone, new clusters of disease will keep popping up. Those clusters will grow and spread. Schools and offices will shut down again. The cycle of inequality will continue. Everything depends on whether the world comes together to ensure that the lifesaving science developed in 2020 saves as many lives as possible in 2021.

Existential crises such as these leave no facet of life untouched. But solutions that are worthy of these historic moments also have ripples. Demanding an inclusive response will save lives and livelihoods now—and create a foundation for a post-pandemic world that is stronger, more equal, and more resilient.

It’s not too soon to start thinking about the next pandemic.

Bill: One of the questions I get asked the most is when I think the world will get back to normal. I understand why. We all want to return to the way things were before COVID-19. But there's one area where I hope we never go back: our complacency about pandemics.

The unfortunate reality is that COVID-19 might not be the last pandemic. We don’t know when the next one will strike, or whether it will be a flu, a coronavirus, or some new disease we’ve never seen before. But what we do know is that we can’t afford to be caught flat-footed again. The threat of the next pandemic will always be hanging over our heads—unless the world takes steps to prevent it.

The good news is that we can get ahead of infectious disease outbreaks. Although the world failed to prepare for COVID-19 in many ways, we’re still benefiting from actions taken in response to past outbreaks. For example, the Ebola epidemic made it clear that we needed to accelerate the development of new vaccines. So, our foundation partnered with governments and other funders to create the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations . CEPI helped fund a number of COVID-19 candidates—including the Moderna and Oxford AstraZeneca vaccines—and is deeply involved in the vaccine equity work that Melinda wrote about.

To prevent the hardship of this last year from happening again, pandemic preparedness must be taken as seriously as we take the threat of war. The world needs to double down on investments in R&D and organizations like CEPI that have proven invaluable with COVID-19. We also need to build brand-new capabilities that don’t exist yet.

Stopping the next pandemic will require spending tens of billions of dollars per year—a big investment, but remember that the COVID-19 pandemic is estimated to cost the world $28 trillion. The world needs to spend billions to save trillions (and prevent millions of deaths). I think of this as the best and most cost-efficient insurance policy the world could buy.

The bulk of this investment needs to come from rich countries. Low- and middle-income countries and foundations like ours have a role to play, but governments from high-income nations need to lead the charge here because the benefits for them are so huge. If you live in a rich country, it’s in your best interest for your government to go big on pandemic preparedness around the world. Melinda wrote that COVID-19 anywhere is a threat to health everywhere; the same is true of the next potential pandemic. The tools and systems created to stop pathogens in their tracks need to span the globe, including in low- and middle-income countries.

To start, governments need to continue investing in the scientific tools that are getting us through this current pandemic —even after COVID-19 is behind us. New breakthroughs will give us a leg up the next time a new disease emerges. It took months to get enough testing capacity for COVID-19 in the United States. But it’s possible to build up diagnostics that can be deployed very quickly. By the next pandemic, I’m hopeful we’ll have what I call mega-diagnostic platforms, which could test as much as 20 percent of the global population every week.

A lab technician inserts a swab into a COVID-19 rapid test machine. (Angus Mordant/Getty Images)

I’m confident that we will have better treatments next time, too. One of the most promising COVID-19 therapeutics is monoclonal antibodies. If a patient gets them early enough, you can potentially reduce the death rate by as much as 80 percent.

Our foundation has funded research into monoclonal antibodies as a potential treatment for flu and malaria for over a decade. These antibodies can be used to treat any number of diseases. The downside is that they’re time-consuming to develop and manufacture. It will likely take another five years of perfecting the technology before we can quickly churn them out in response to new pathogens.

I also expect we’ll see huge advances over the next five years in our ability to develop new vaccines—in large part due to the success of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. I wrote about this at length in my Year in Review , but the short version is that mRNA vaccines are a new type of vaccine that delivers instructions to teach your body to fight off a pathogen. Although our foundation has been funding research into this new platform since 2014, no mRNA vaccine had been approved for use before last month . This pandemic has massively sped up the platform’s development process.

Just as I think we’ll see huge improvements in diagnostics and monoclonal antibodies, I predict that mRNA vaccines will become faster to develop, easier to scale, and more stable to store over the next five to ten years. That would be a huge breakthrough, both for future pandemics and for other global health challenges. mRNA vaccines are a promising platform for diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. The R&D progress made as a result of COVID-19 might one day give us the tools we need to finally end these deadly diseases.

When it comes to preventing pandemics, scientific tools alone aren’t enough. The world also needs field-based capabilities that constantly monitor for troubling pathogens and can be spun up as soon as they’re needed. There is still a lot to be figured out in terms of specifics, including where these capabilities would be housed and how exactly they’d be structured. But here is my broad thinking:

First, we need to spot disease outbreaks as soon as they happen, wherever they happen. That will require a global alert system , which we don’t have at large scale today. The backbone of this system would be diagnostic testing. Let’s say you’re a nurse at a rural health clinic. You notice that more patients are showing up with coughs than you’d expect for this time of year, or maybe even that more people are dying than normal. So, you test for common pathogens. If none of them test positive, your sample is sent elsewhere to get sequenced for further investigation.

Workers assemble COVID-19 testing kits at the Incas Diagnostics lab in Kumasi, Ghana.

If your sample turns out to be some super infectious—or entirely new—pathogen, a group of infectious disease first responders springs into action. Think of this corps as a pandemic fire squad. Just like firefighters, they’re fully trained professionals who are ready to respond to potential crises at a moment’s notice. When they aren’t actively responding to an outbreak, they keep their skills sharp by working on diseases like malaria and polio. I estimate that we need somewhere around 3,000 responders throughout the world.

To learn how to best use these first responders, the world needs to regularly run germ games —simulations that let us practice, analyze, and improve how we respond to disease outbreaks, just as war games let the military prepare for real-life warfare. Speed matters in a pandemic. The faster you act, the faster you cut off exponential growth of the virus. Places that had recent experiences with respiratory outbreaks—such as Taiwan with SARS and South Korea with MERS—responded to COVID-19 more quickly than other places because they already knew what to do. Running simulations will make sure everyone is ready to act quickly next time.

Ultimately, the thing that makes me the most optimistic that we’ll be ready next time is also the simplest: The world now understands how seriously we should take pandemics. No one needs to be convinced that an infectious disease could kill millions of people or shut down the global economy. The pain of this past year will be seared into people’s thinking for a generation. I am hopeful that we’ll see broad support for efforts that make sure we never have to experience this hardship again. We’re already seeing new pandemic preparedness strategies emerge, including from this year’s UK-led G7, and I expect to see more in the months and years to come.

The world wasn’t ready for the COVID-19 pandemic. I think next time will be different.

A healthier, brighter future for all

(Above) Medical workers in Prato, Italy wear photos of themselves on top of their personal protection equipment. (Alberto Pizzoli/AFP via Getty Images). (Below) A woman helps her daughter with an online lesson in Jakarta, Indonesia. (Jefta Images/Barcroft Media via Getty Images).

(Above) A teacher works with students in a classroom equipped with plastic dividers to reduce COVID-19 transmission in Bangkok, Thailand. (Romeo Gacad/AFP via Getty Images). (Below) A school worker hands out free meals to students in Melbourne, Australia. (William West/AFP via Getty Images).

As hard as it is to imagine right now while so many people are still suffering from COVID-19, this pandemic will come to an end someday. When that moment comes, it will be a testament to the remarkable leaders who have emerged over the last year to steer us through this crisis.

When we say “leaders,” we don’t just mean the policymakers and elected officials who are in charge of the official government response. We’re also talking about the healthcare workers who are enduring unimaginable trauma on the frontlines. The teachers, parents, and caregivers who are going above and beyond to make sure kids don’t fall behind in school. The scientists and researchers who are working around the clock to stop this virus. Even the neighbors who are cooking extra meals to make sure no one in their community goes hungry.

Their leadership will get us through this pandemic, and we owe it to them to recover in a way that leaves us stronger and more prepared for the next challenge. Overthe last year, a global threat touched nearly every person on the planet. By next year, we hope an equitable, effective COVID-19 response will have reached the whole world, too.

We hope that you and your loved ones are staying safe and healthy in these difficult times.

Times are hard. But I still believe we can make the world better for the next generation. Here's how.

5 posts based on my book about avoiding another global outbreak.

Let’s make this the last pandemic

My new book is all about how we eliminate the pandemic as a threat to humanity.

3 things we can do right now

If we’re going to make COVID-19 the last pandemic, the world needs to get to work right away on these key areas.

This is my personal blog, where I share about the people I meet, the books I'm reading, and what I'm learning. I hope that you'll join the conversation.

Q. How do I create a Gates Notes account?

A. there are three ways you can create a gates notes account:.

- Sign up with Facebook. We’ll never post to your Facebook account without your permission.

- Sign up with Twitter. We’ll never post to your Twitter account without your permission.

- Sign up with your email. Enter your email address during sign up. We’ll email you a link for verification.

Q. Will you ever post to my Facebook or Twitter accounts without my permission?

A. no, never., q. how do i sign up to receive email communications from my gates notes account, a. in account settings, click the toggle switch next to “send me updates from bill gates.”, q. how will you use the interests i select in account settings, a. we will use them to choose the suggested reads that appear on your profile page..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In 2015, leaders from 193 countries agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals—the SDGs. These were big, bold objectives we wanted to achieve by 2030, everything from ending poverty to achieving gender equality. And each year, this report attempts to answer the question, “How is the world doing?”

Bill Gates shares why the Gates Foundation is committing $912 million to help replenish the Global Fund and fight AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. By Bill Gates Chair, Board Member, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is a foundation that supports other organizations who share its guiding belief that every life has equal value. Located in Seattle, Washington, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have an asset trust endowment of 36.2 billion dollars as of September 30, 2012.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation focuses on catalytic philanthropy—investments that can yield massive returns. That means finding areas where governments and private businesses aren’t...

This brief presents the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s model of women and girls’ empowerment, which was developed in partnership with the Gender Team at based in Amsterdam. The model was designed using a process that involved an extensive literature review, alongside consultations with foundation staff, partners,

Melinda Gates Going back at least to Thomas Malthus, who published his An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, people have worried about doomsday scenarios in which food supply can’t keep up with population growth.

When Warren urged Melinda and me to swing for the fences all those years ago, he was talking about the areas our foundation worked on at the time, not climate change. But his advice applies here, too.

After an unprecedented year, Bill and Melinda Gates reflect on losses and lessons in their 2021 Annual Letter: The year global health went local.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is emphasizing three core priorities : containing the global COVID-19 pandemic, rebuilding through an accelerated economic recovery, and

Guided by the belief that every life has equal value, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives. In developing countries, it focuses on improving people’s health and giving them the chance to lift themselves out of hunger and extreme poverty.