Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

Published on 11 April 2022 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on 5 December 2022.

Experiments are used to study causal relationships . You manipulate one or more independent variables and measure their effect on one or more dependent variables.

Experimental design means creating a set of procedures to systematically test a hypothesis . A good experimental design requires a strong understanding of the system you are studying.

There are five key steps in designing an experiment:

- Consider your variables and how they are related

- Write a specific, testable hypothesis

- Design experimental treatments to manipulate your independent variable

- Assign subjects to groups, either between-subjects or within-subjects

- Plan how you will measure your dependent variable

For valid conclusions, you also need to select a representative sample and control any extraneous variables that might influence your results. If if random assignment of participants to control and treatment groups is impossible, unethical, or highly difficult, consider an observational study instead.

Table of contents

Step 1: define your variables, step 2: write your hypothesis, step 3: design your experimental treatments, step 4: assign your subjects to treatment groups, step 5: measure your dependent variable, frequently asked questions about experimental design.

You should begin with a specific research question . We will work with two research question examples, one from health sciences and one from ecology:

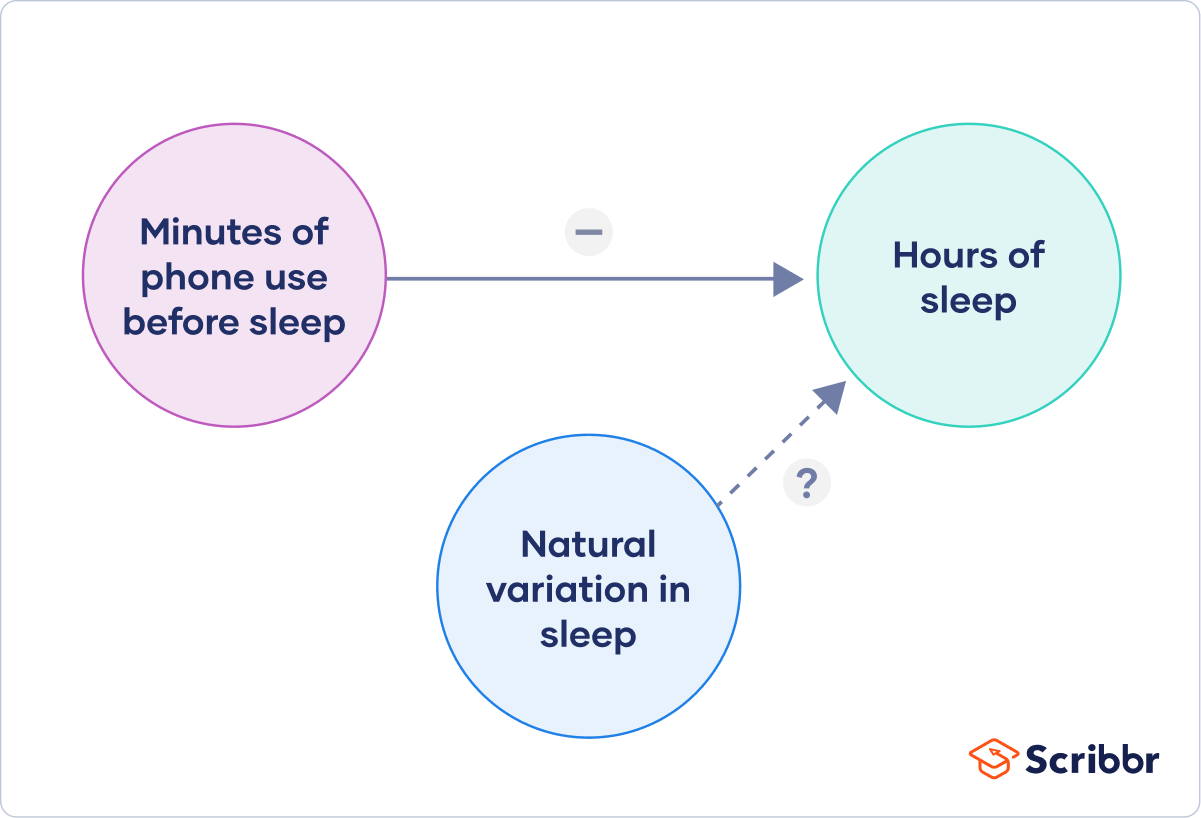

To translate your research question into an experimental hypothesis, you need to define the main variables and make predictions about how they are related.

Start by simply listing the independent and dependent variables .

Then you need to think about possible extraneous and confounding variables and consider how you might control them in your experiment.

Finally, you can put these variables together into a diagram. Use arrows to show the possible relationships between variables and include signs to show the expected direction of the relationships.

Here we predict that increasing temperature will increase soil respiration and decrease soil moisture, while decreasing soil moisture will lead to decreased soil respiration.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Now that you have a strong conceptual understanding of the system you are studying, you should be able to write a specific, testable hypothesis that addresses your research question.

The next steps will describe how to design a controlled experiment . In a controlled experiment, you must be able to:

- Systematically and precisely manipulate the independent variable(s).

- Precisely measure the dependent variable(s).

- Control any potential confounding variables.

If your study system doesn’t match these criteria, there are other types of research you can use to answer your research question.

How you manipulate the independent variable can affect the experiment’s external validity – that is, the extent to which the results can be generalised and applied to the broader world.

First, you may need to decide how widely to vary your independent variable.

- just slightly above the natural range for your study region.

- over a wider range of temperatures to mimic future warming.

- over an extreme range that is beyond any possible natural variation.

Second, you may need to choose how finely to vary your independent variable. Sometimes this choice is made for you by your experimental system, but often you will need to decide, and this will affect how much you can infer from your results.

- a categorical variable : either as binary (yes/no) or as levels of a factor (no phone use, low phone use, high phone use).

- a continuous variable (minutes of phone use measured every night).

How you apply your experimental treatments to your test subjects is crucial for obtaining valid and reliable results.

First, you need to consider the study size : how many individuals will be included in the experiment? In general, the more subjects you include, the greater your experiment’s statistical power , which determines how much confidence you can have in your results.

Then you need to randomly assign your subjects to treatment groups . Each group receives a different level of the treatment (e.g. no phone use, low phone use, high phone use).

You should also include a control group , which receives no treatment. The control group tells us what would have happened to your test subjects without any experimental intervention.

When assigning your subjects to groups, there are two main choices you need to make:

- A completely randomised design vs a randomised block design .

- A between-subjects design vs a within-subjects design .

Randomisation

An experiment can be completely randomised or randomised within blocks (aka strata):

- In a completely randomised design , every subject is assigned to a treatment group at random.

- In a randomised block design (aka stratified random design), subjects are first grouped according to a characteristic they share, and then randomly assigned to treatments within those groups.

Sometimes randomisation isn’t practical or ethical , so researchers create partially-random or even non-random designs. An experimental design where treatments aren’t randomly assigned is called a quasi-experimental design .

Between-subjects vs within-subjects

In a between-subjects design (also known as an independent measures design or classic ANOVA design), individuals receive only one of the possible levels of an experimental treatment.

In medical or social research, you might also use matched pairs within your between-subjects design to make sure that each treatment group contains the same variety of test subjects in the same proportions.

In a within-subjects design (also known as a repeated measures design), every individual receives each of the experimental treatments consecutively, and their responses to each treatment are measured.

Within-subjects or repeated measures can also refer to an experimental design where an effect emerges over time, and individual responses are measured over time in order to measure this effect as it emerges.

Counterbalancing (randomising or reversing the order of treatments among subjects) is often used in within-subjects designs to ensure that the order of treatment application doesn’t influence the results of the experiment.

Finally, you need to decide how you’ll collect data on your dependent variable outcomes. You should aim for reliable and valid measurements that minimise bias or error.

Some variables, like temperature, can be objectively measured with scientific instruments. Others may need to be operationalised to turn them into measurable observations.

- Ask participants to record what time they go to sleep and get up each day.

- Ask participants to wear a sleep tracker.

How precisely you measure your dependent variable also affects the kinds of statistical analysis you can use on your data.

Experiments are always context-dependent, and a good experimental design will take into account all of the unique considerations of your study system to produce information that is both valid and relevant to your research question.

Experimental designs are a set of procedures that you plan in order to examine the relationship between variables that interest you.

To design a successful experiment, first identify:

- A testable hypothesis

- One or more independent variables that you will manipulate

- One or more dependent variables that you will measure

When designing the experiment, first decide:

- How your variable(s) will be manipulated

- How you will control for any potential confounding or lurking variables

- How many subjects you will include

- How you will assign treatments to your subjects

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that, done correctly, an observational study will never influence the responses or behaviours of participants. Experimental designs will have a treatment condition applied to at least a portion of participants.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

In a between-subjects design , every participant experiences only one condition, and researchers assess group differences between participants in various conditions.

In a within-subjects design , each participant experiences all conditions, and researchers test the same participants repeatedly for differences between conditions.

The word ‘between’ means that you’re comparing different conditions between groups, while the word ‘within’ means you’re comparing different conditions within the same group.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bevans, R. (2022, December 05). A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 11 November 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/guide-to-experimental-design/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

IMAGES

VIDEO