- Humanities ›

- Philosophy ›

- Philosophical Theories & Ideas ›

Would You Kill One Person to Save Five?

Understanding the “Trolley Dilemma”

- Philosophical Theories & Ideas

- Major Philosophers

- Ph.D., Philosophy, The University of Texas at Austin

- M.A., Philosophy, McGill University

- B.A., Philosophy, University of Sheffield

Philosophers love to conduct thought experiments. Often these involve rather bizarre situations, and critics wonder how relevant these thought experiments are to the real world. But the point of the experiments is to help us clarify our thinking by pushing it to the limits. The “trolley dilemma” is one of the most famous of these philosophical imaginings.

The Basic Trolley Problem

A version of this moral dilemma was first put forward in 1967 by the British moral philosopher Phillipa Foot, well-known as one of those responsible for reviving virtue ethics.

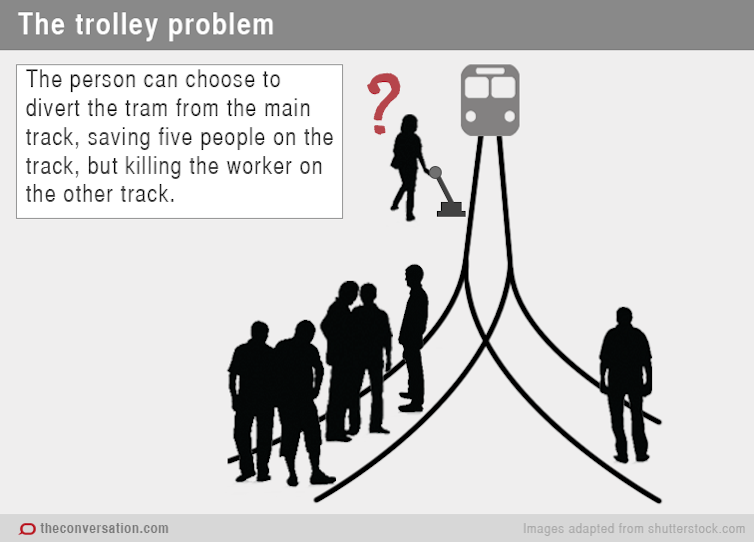

Here’s the basic dilemma: A tram is running down a track and is out control. If it continues on its course unchecked and undiverted, it will run over five people who have been tied to the tracks. You have the chance to divert it onto another track simply by pulling a lever. If you do this, though, the tram will kill a man who happens to be standing on this other track. What should you do?

The Utilitarian Response

For many utilitarians, the problem is a no-brainer. Our duty is to promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Five lives saved is better than one life saved. Therefore, the right thing to do is to pull the lever.

Utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism. It judges actions by their consequences. But there are many who think that we have to consider other aspects of action as well. In the case of the trolley dilemma, many are troubled by the fact that if they pull the lever they will be actively engaged in causing the death of an innocent person. According to our normal moral intuitions, this is wrong, and we should pay some heed to our normal moral intuitions.

So-called “rule utilitarians” may well agree with this point of view. They hold that we should not judge every action by its consequences. Instead, we should establish a set of moral rules to follow according to which rules will promote the greatest happiness of the greatest number in the long term. And then we should follow those rules, even if in specific cases doing so may not produce the best consequences.

But so-called “act utilitarians” judge each act by its consequences; so they will simply do the math and pull the lever. Moreover, they will argue that there is no significant difference between causing a death by pulling the lever and not preventing a death by refusing to pull the lever. One is equally responsible for the consequences in either case.

Those who think that it would be right to divert the tram often appeal to what philosophers call the doctrine of double effect. Simply put, this doctrine states that it is morally acceptable to do something that causes a serious harm in the course of promoting some greater good if the harm in question is not an intended consequence of the action but is, rather, an unintended side-effect. The fact that the harm caused is predictable doesn’t matter. What matters is whether or not the agent intends it.

The doctrine of double effect plays an important role in just war theory. It has often been used to justify certain military actions which cause “collateral damage.” An example of such an action would be the bombing of an ammunition dump that not only destroys the military target but also causes a number of civilian deaths.

Studies show that the majority of people today, at least in modern Western societies, say that they would pull the lever. However, they respond differently when the situation is tweaked.

The Fat Man on the Bridge Variation

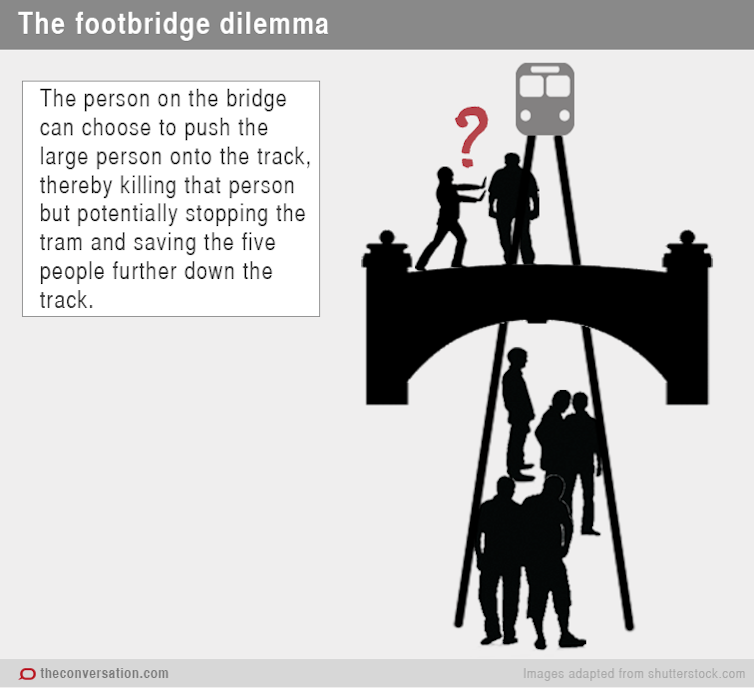

The situation is the same as before: a runaway tram threatens to kill five people. A very heavy man is sitting on a wall on a bridge spanning the track. You can stop the train by pushing him off the bridge onto the track in front of the train. He will die, but the five will be saved. (You can’t opt to jump in front of the tram yourself since you aren’t big enough to stop it.)

From a simple utilitarian point of view, the dilemma is the same — do you sacrifice one life to save five? — and the answer is the same: yes. Interestingly, however, many people who would pull the lever in the first scenario would not push the man in this second scenario. This raises two questions:

The Moral Question: If Pulling the Lever Is Right, Why Would Pushing the Man Be Wrong?

One argument for treating the cases differently is to say that the doctrine of double effect no longer applies if one pushes the man off the bridge. His death is no longer an unfortunate side-effect of your decision to divert the tram; his death is the very means by which the tram is stopped. So you can hardly say in this case that when you pushed him off the bridge you weren’t intending to cause his death.

A closely related argument is based on a moral principle made famous by the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). According to Kant , we should always treat people as ends in themselves, never merely as a means to our own ends. This is commonly known, reasonably enough, as the “ends principle.” It is fairly obvious that if you push the man off the bridge to stop the tram, you are using him purely as a means. To treat him as the end would be to respect the fact that he is a free, rational being, to explain the situation to him, and suggest that he sacrifice himself to save the lives of those tied to the track. Of course, there is no guarantee that he would be persuaded. And before the discussion had got very far the tram would have probably already passed under the bridge!

The Psychological Question: Why Will People Pull the Lever but Not Push the Man?

Psychologists are concerned not with establishing what is right or wrong but with understanding why people are so much more reluctant to push a man to his death than to cause his death by pulling a lever. The Yale psychologist Paul Bloom suggests that the reason lies in the fact that our causing the man’s death by actually touching him arouses in us a much stronger emotional response. In every culture, there is some sort of taboo against murder. An unwillingness to kill an innocent person with our own hands is deeply ingrained in most people. This conclusion seems to be supported by people’s response to another variation on the basic dilemma.

The Fat Man Standing on the Trapdoor Variation

Here the situation is the same as before, but instead of sitting on a wall the fat man is standing on a trapdoor built into the bridge. Once again you can now stop the train and save five lives by simply pulling a lever. But in this case, pulling the lever will not divert the train. Instead, it will open the trapdoor, causing the man to fall through it and onto the track in front of the train.

Generally speaking, people are not as ready to pull this lever as they are to pull the lever that diverts the train. But significantly more people are willing to stop the train in this way than are prepared to push the man off the bridge.

The Fat Villain on the Bridge Variation

Suppose now that the man on the bridge is the very same man who has tied the five innocent people to the track. Would you be willing to push this person to his death to save the five? A majority say they would, and this course of action seems fairly easy to justify. Given that he is willfully trying to cause innocent people to die, his own death strikes many people as thoroughly deserved. The situation is more complicated, though, if the man is simply someone who has done other bad actions. Suppose in the past he has committed murder or rape and that he hasn’t paid any penalty for these crimes. Does that justify violating Kant’s ends principle and using him as a mere means?

The Close Relative on the Track Variation

Here is one last variation to consider. Go back to the original scenario–you can pull a lever to divert the train so that five lives are saved and one person is killed–but this time the one person who will be killed is your mother or your brother. What would you do in this case? And what would be the right thing to do?

A strict utilitarian may have to bite the bullet here and be willing to cause the death of their nearest and dearest. After all, one of the basic principles of utilitarianism is that everyone’s happiness counts equally. As Jeremy Bentham, one of the founders of modern utilitarianism put it: Everyone counts for one; no-one for more than one. So sorry mom!

But this is most definitely not what most people would do. The majority may lament the deaths of the five innocents, but they cannot bring themselves to bring about the death of a loved one in order to save the lives of strangers. That is most understandable from a psychological point of view. Humans are primed both in the course of evolution and through their upbringing to care most for those around them. But is it morally legitimate to show a preference for one’s own family?

This is where many people feel that strict utilitarianism is unreasonable and unrealistic. Not only will we tend to naturally favor our own family over strangers, but many think that we ought to. For loyalty is a virtue, and loyalty to one’s family is about as basic a form of loyalty as there is. So in many people’s eyes, to sacrifice family for strangers goes against both our natural instincts and our most fundamental moral intuitions.

- Moral Philosophy According to Immanuel Kant

- What Is Ethical Egoism?

- An Introduction to Virtue Ethics

- Psychological Violence

- Soft Determinism Explained

- 3 Stoic Strategies for Becoming Happier

- The 5 Great Schools of Ancient Greek Philosophy

- The Ethics of Lying

- What Does It Mean to Live the Good Life?

- The Philosophy of Honesty

- Psychological Egoism

- The Self in Philosophy

- On Being Cynical

- Nietzsche's Idea of Eternal Recurrence

- Humpty Dumpty's Philosophy of Language

- What Does Nietzsche Mean When He Says That God Is Dead?

The trolley dilemma: would you kill one person to save five?

Senior Lecturer in Philosophy, University of Notre Dame Australia

Disclosure statement

Laura D'Olimpio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The University of Notre Dame Australia provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Imagine you are standing beside some tram tracks. In the distance, you spot a runaway trolley hurtling down the tracks towards five workers who cannot hear it coming. Even if they do spot it, they won’t be able to move out of the way in time.

As this disaster looms, you glance down and see a lever connected to the tracks. You realise that if you pull the lever, the tram will be diverted down a second set of tracks away from the five unsuspecting workers.

However, down this side track is one lone worker, just as oblivious as his colleagues.

So, would you pull the lever, leading to one death but saving five?

This is the crux of the classic thought experiment known as the trolley dilemma, developed by philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967 and adapted by Judith Jarvis Thomson in 1985.

The trolley dilemma allows us to think through the consequences of an action and consider whether its moral value is determined solely by its outcome.

The trolley dilemma has since proven itself to be a remarkably flexible tool for probing our moral intuitions, and has been adapted to apply to various other scenarios, such as war, torture, drones, abortion and euthanasia.

Now consider now the second variation of this dilemma.

Imagine you are standing on a footbridge above the tram tracks. You can see the runaway trolley hurtling towards the five unsuspecting workers, but there’s no lever to divert it.

However, there is large man standing next to you on the footbridge. You’re confident that his bulk would stop the tram in its tracks.

So, would you push the man on to the tracks, sacrificing him in order to stop the tram and thereby saving five others?

The outcome of this scenario is identical to the one with the lever diverting the trolley onto another track: one person dies; five people live. The interesting thing is that, while most people would throw the lever, very few would approve of pushing the fat man off the footbridge.

Thompson and other philosophers have given us other variations on the trolley dilemma that are also scarily entertaining. Some don’t even include trolleys.

Imagine you are a doctor and you have five patients who all need transplants in order to live. Two each require one lung, another two each require a kidney and the fifth needs a heart.

In the next ward is another individual recovering from a broken leg. But other than their knitting bones, they’re perfectly healthy. So, would you kill the healthy patient and harvest their organs to save five others?

Again, the consequences are the same as the first dilemma, but most people would utterly reject the notion of killing the healthy patient.

Actions, intentions and consequences

If all the dilemmas above have the same consequence, yet most people would only be willing to throw the lever, but not push the fat man or kill the healthy patient, does that mean our moral intuitions are not always reliable, logical or consistent?

Perhaps there’s another factor beyond the consequences that influences our moral intuitions?

Foot argued that there’s a distinction between killing and letting die. The former is active while the latter is passive.

In the first trolley dilemma, the person who pulls the lever is saving the life of the five workers and letting the one person die. After all, pulling the lever does not inflict direct harm on the person on the side track.

But in the footbridge scenario, pushing the fat man over the side is in intentional act of killing.

This is sometimes described as the principle of double effect , which states that it’s permissible to indirectly cause harm (as a side or “double” effect) if the action promotes an even greater good. However, it’s not permissible to directly cause harm, even in the pursuit of a greater good.

Thompson offered a different perspective. She argued that moral theories that judge the permissibility of an action based on its consequences alone, such as consequentialism or utilitarianism , cannot explain why some actions that cause killings are permissible while others are not.

If we consider that everyone has equal rights, then we would be doing something wrong in sacrificing one even if our intention was to save five.

Research done by neuroscientists has investigated which parts of the brain were activated when people considered the first two variations of the trolley dilemma.

They noted that the first version activates our logical, rational mind and thus if we decided to pull the lever it was because we intended to save a larger number of lives.

However, when we consider pushing the bystander, our emotional reasoning becomes involved and we therefore feel differently about killing one in order to save five.

Are our emotions in this instance leading us to the correct action? Should we avoid sacrificing one, even if it is to save five?

Real world dilemmas

The trolley dilemma and its variations demonstrate that most people approve of some actions that cause harm, yet other actions with the same outcome are not considered permissible.

Not everyone answers the dilemmas in the same way, and even when people agree, they may vary in their justification of the action they defend.

These thought experiments have been used to stimulate discussion about the difference between killing versus letting die, and have even appeared, in one form or another, in popular culture, such as the film Eye In The Sky .

- moral dilemma

Deputy Director of Medical Student Education

Public Policy Editor

ARDC Project Management Office Manager

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Next Stop: ‘Trolley Problem’

What to Know The trolley problem is a thought experiment in ethics about a fictional scenario in which an onlooker has the choice to save 5 people in danger of being hit by a trolley, by diverting the trolley to kill just 1 person. The term is often used more loosely with regard to any choice that seemingly has a trade-off between what is good and what sacrifices are "acceptable," if at all.

Holy forking shirtballs

Trolley problem is the name given to a thought experiment in philosophy and psychology. It has sprouted a number of variations, but is distilled to something like this: you are riding in a trolley without functioning brakes, headed toward a switch in the tracks. On the current track stand five people who stand to be killed if the trolley continues on its path. You have access to a switch that would make the trolley change to the other track, but another individual stands there. That person is certain to be killed if the switch is activated.

So do you switch tracks or not?

Utilitarianism vs. Deontologicalism

The problem comes up in discussions of ethics and moral choice, pitting the idea of responsibility against the measurement of good by an end result. On the one hand, it might seem obvious that the deaths of five would be a worse result than the death of an individual. On the other hand, in order to change course, you have to make the active decision to put that doomed individual in the path of the trolley.

The school of thought that killing the one person to save the five is usually aligned with utilitarianism (the belief that the best actions are those that result in the greatest good for the greatest number of people). Another school, that of deontological ethics, argues that an action is inherently right or wrong regardless of the consequences. This school would favor against taking the action that results in the killing of the individual on the other track.

The trolley dilemmas vividly distilled the distinction between two different concepts of morality: that we should choose the action with the best overall consequences (in philosophy-speak, utilitarianism is the most well-known example of this), like only one person dying instead of five, and the idea that we should always adhere to strict duties, like “never kill a human being.” The subtle differences between the scenarios provided helped to articulate influential concepts, like the distinction between actively killing someone versus passively letting them die, that continue to inform contemporary debates in law and public policy. The trolley problem has also been, and continues to be, a compelling teaching tool within philosophy — Lauren Cassani Davis, The Atlantic , 9 Oct. 2015 Twitter users are pointing out just how ridiculous the capitalist dilemma is right now — it's barely a trolley problem at all. Why put so much weight on economic development when there are literal human lives at risk? — Morgan Sung, Mashable , 24 Mar. 2020

History of the Trolley Problem

English philosopher Philippa Foot is credited with introducing this version of the trolley problem in 1967, though another philosopher, Judith Thomson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is credited with coining the term trolley problem . (Thomson also posed an alternate scenario, which involves the question of whether a bystander on an overpass should throw a fat man over the rail to his death in order to stop a trolley below from killing the five people on the track.)

Recent events have elevated the trolley problem to prominence in popular culture and political discourse. Notably, it served as a device in several episodes of the NBC sitcom The Good Place , whose characters are challenged with finding a path to goodness in the afterlife. As Chidi Anagonye, a professor of moral philosophy, leads discussions of ethical decision-making despite being chronically indecisive himself, he participates in the trolley problem on an actual trolley to bloody comic effect. (The trolley problem has also figured into the storylines of two other series, The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Orange Is the New Black .)

The trolley problem is one that can be easily visualized, and it can be used as a metaphor in so many scenarios that it has naturally become the subject of a number of internet memes.

"The trolley problem is just one more depressing example of academic philosophers’ obsession with concentrating on selected, artificial examples so as to dodge the stress of looking at real issues." - Mary Midgley pic.twitter.com/Zx9KjSaN58 — Ethics in Bricks (@EthicsInBricks) April 8, 2020

The trolley problem is invoked in political decision-making, and has surfaced in discussions concerning the response of leaders to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the moral implications of taking action that could reduce overall harm while endangering a select number in the process. In the technology sector, a scenario that closely resembles a literal trolley problem comes up with regard to autonomous vehicles and how to program them to harm the fewest number of people in the event of inevitable collision.

Experts feel the proposed $291 million budget will be insufficient, not to mention that the massive undertaking will take dedicated cooperation between federal, state, and local government. Also, turning our eye home has lessened resources slated to go to fighting AIDS abroad, but you’ll have to solve that particular Trolley Problem for yourself. — Jef Rouner, The Houston Press , 3 May 2019 The Predator drone, conceived in the 1990s and flown for millions of hours since then, has changed the way the US fights wars, both for better and for worse. It keeps US troops out of harm's way, but it also removes them from the in-the-moment decisions of war. Predator strikes can be incredibly precise, but they have killed hundreds of civilians. Drone warfare has been hotly debated since its inception—it's both a technological debate and a moral one, a sort of Trolley Problem for the skies. — David Pierce, _ Wired _, 1 Feb. 2018

The actual philosophical concepts aren't as important right now as the dilemma itself. It's supposed to be hard. Either way, you're on a trolley that smooshes someone and that stinks. If there were an easy answer, it wouldn't be a "problem." It would be the Fun Trolley Puzzle! 3/ — Ken Tremendous (@KenTremendous) March 24, 2020

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Arts & Culture

8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, pop rhetoric: our favorites, if you like to complain about 'decimate'..., the real origin of 'supercalifragilistic', 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), the longest long words list, pilfer: how to play and win, 15 bird sounds and the birds who make them, 8 words with fascinating histories, birds say the darndest things, grammar & usage, using bullet points ( • ), point of view: it's personal, 31 useful rhetorical devices, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), plural and possessive names: a guide.

IMAGES

VIDEO