Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

How Does Social Context Influence Our Brain and Behavior?

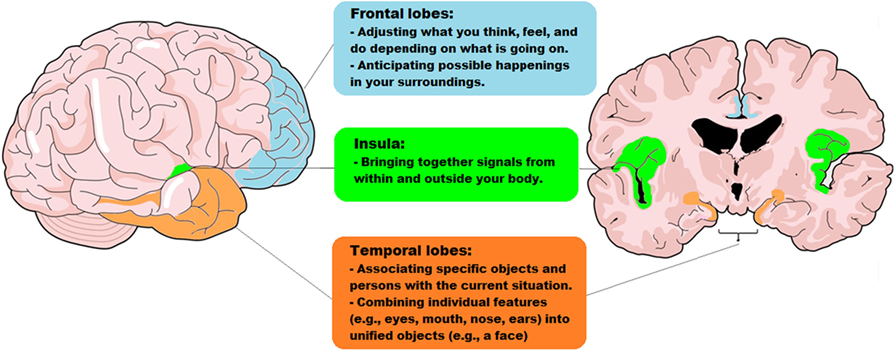

When we interact with others, the context in which our actions take place plays a major role in our behavior. This means that our understanding of objects, words, emotions, and social cues may differ depending on where we encounter them. Here, we explain how context affects daily mental processes, ranging from how people see things to how they behave with others. Then, we present the social context network model. This model explains how people process contextual cues when they interact, through the activity of the frontal, temporal, and insular brain regions. Next, we show that when those brain areas are affected by some diseases, patients find it hard to process contextual cues. Finally, we describe new ways to explore social behavior through brain recordings in daily situations.

Introduction

Everything you do is influenced by the situation in which you do it. The situation that surrounds an action is called its context. In fact, analyzing context is crucial for social interaction and even, in some cases, for survival. Imagine you see a man in fear: your reaction depends on his facial expression (e.g., raised eyebrows, wide-open eyes) and also on the context of the situation. The context can be external (is there something frightening around?) or internal (am I calm or am I also scared?). Such contextual cues are crucial to your understanding of any situation.

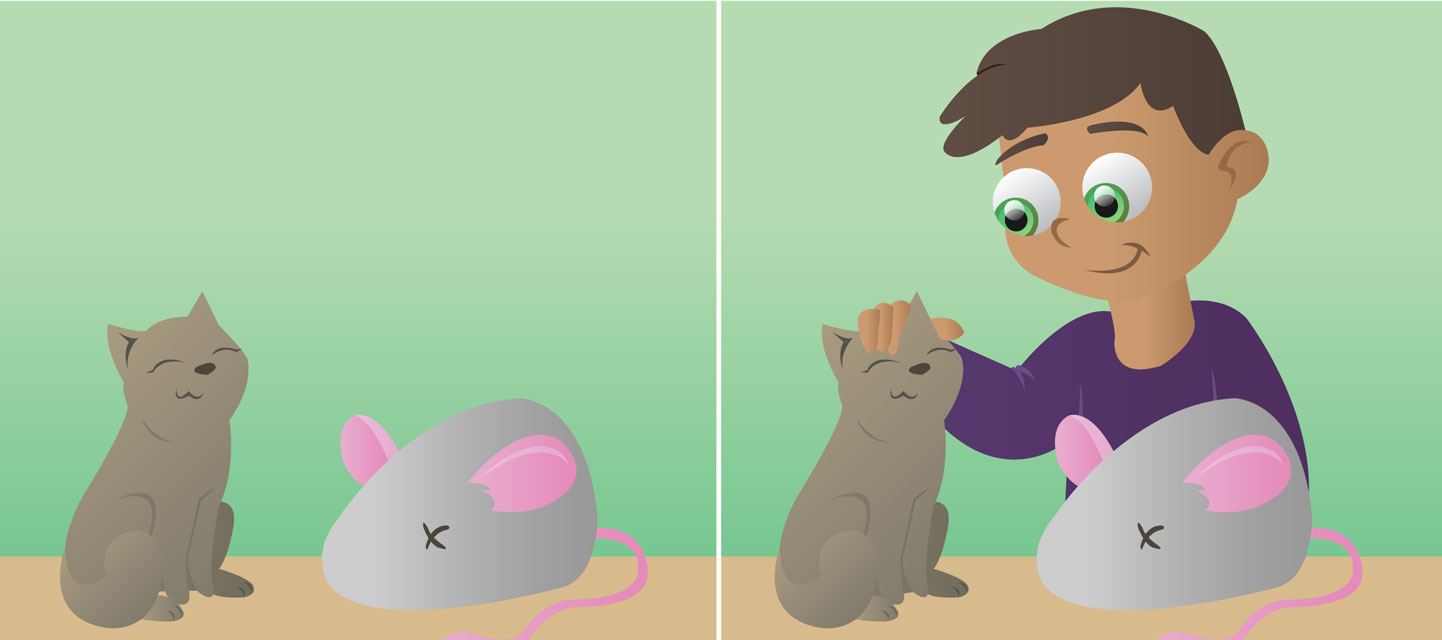

Context shapes all processes in your brain, from visual perception to social interactions [ 1 ]. Your mind is never isolated from the world around you. The specific meaning of an object, word, emotion, or social event depends on context ( Figure 1 ). Context may be evident or subtle, real or imagined, conscious or unconscious. Simple optical illusions demonstrate the importance of context ( Figures 1A,B ). In the Ebbinghaus illusion ( Figure 1A ), rings of circles surround two central circles. The central circles are the same size, but one appears to be smaller than the other. This is so because the surrounding circles provide a context. This context affects your perception of the size of the central circles. Quite interesting, right? Likewise, in the Cafe Wall Illusion ( Figure 1B ), context affects your perception of the lines’ orientation. The lines are parallel, but you see them as convergent or divergent. You can try focusing on the middle line of the figure and check it with a ruler. Contextual cues also help you recognize objects in a scene [ 2 ]. For instance, it can be easier to recognize letters when they are in the context of a word. Thus, you can see the same array of lines as either an H or an A ( Figure 1C ). Certainly, you did not read that phrase as “TAE CHT”, correct? Lastly, contextual cues are also important for social interaction. For instance, visual scenes, voices, bodies, other faces, and words shape how you perceive emotions in a face [ 3 ]. If you see Figure 1D in isolation, the woman may look furious. But look again, this time at Figure 1E . Here you see an ecstatic Serena Williams after she secured the top tennis ranking. This shows that recognizing emotions depends on additional information that is not present in the face itself.

- Figure 1 - Contextual affects how you see things.

- A,B. The visual context affects how you see shapes. C. Context also plays an important role in object recognition. Context-related objects are easier to recognize. “THE CAT” is a good example of contextual effects in letter recognition (reproduced with permission from Chun [ 2 ]). D,E. Context also affects how you recognize an emotion [by Hanson K. Joseph (Own work), CC BY-SA 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 ), via Wikimedia Commons].

Contextual cues also help you make sense of other situations. What is appropriate in one place may not be appropriate in another. Making jokes is OK when studying with your friends, but not OK during the actual exam. Also, context affects how you feel when you see something happening to another person. Picture someone being beaten on the street. If the person being beaten is your best friend, would you react in the same way as if he were a stranger? The reason why you probably answered “no” is that your empathy may be influenced by context. Context will determine whether you jump in to help or run away in fear. In sum, social situations are shaped by contextual factors that affect how you feel and act.

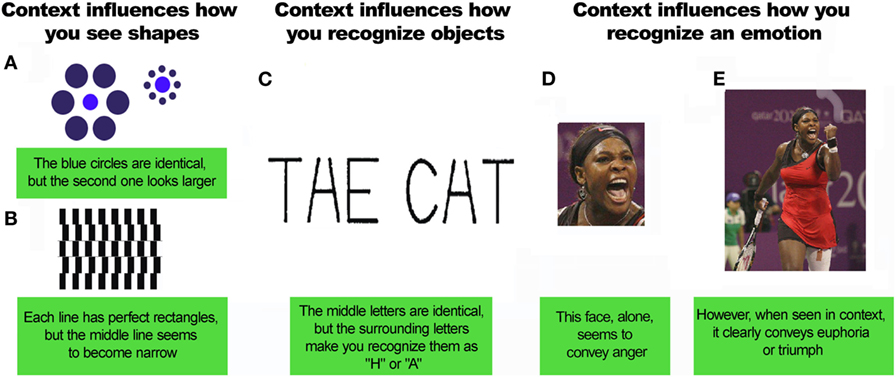

Contextual cues are important for interpreting social situations. Yet, they have been largely ignored in the world of science. To fill this gap, our group proposed the social context network model [ 1 ]. This model describes a brain network that integrates contextual information during social processes. This brain network combines the activity of several different areas of the brain, namely frontal, temporal, and insular brain areas ( Figure 2 ). It is true that many other brain areas are involved in processing contextual information. For instance, the context of an object that you can see affects processes in the vision areas of your brain [ 4 ]. However, the network proposed by our model includes the main areas involved in social context processing. Even contextual visual recognition involves activity of temporal and frontal regions included in our model [ 5 ].

- Figure 2 - The parts of the brain that work together, in the social context network model.

- This model proposes that social contextual cues are processed by a network of specific brain regions. This network is made up of frontal (light blue), temporal (orange), and insular (green) brain regions and the connections between these regions.

How Does Your Brain Process Contextual Cues in Social Scenarios?

To interpret context in social settings, your brain relies on a network of brain regions, including the frontal, temporal, and insular regions. Figure 2 shows the frontal regions in light blue. These regions help you update contextual information when you focus on something (say, the traffic light as you are walking down the street). That information helps you anticipate what might happen next, based on your previous experiences. If there is a change in what you are seeing (as you keep walking down the street, a mean-looking Doberman appears), the frontal regions will activate and update predictions (“this may be dangerous!”). These predictions will be influenced by the context (“oh, the dog is on a leash”) and your previous experience (“yeah, but once I was attacked by a dog and it was very bad!”). If a person’s frontal regions are damaged, he/she will find it difficult to recognize the influence of context. Thus, the Doberman may not be perceived as a threat, even if this person has been attacked by other dogs before! The main role of the frontal regions is to predict the meaning of actions by analyzing the contextual events that surround the actions.

Figure 2 shows the insular regions, also called the insula, in green. The insula combines signals from within and outside your body. The insula receives signals about what is going on in your guts, heart, and lungs. It also supports your ability to experience emotions. Even the butterflies you sometimes feel in your stomach depend on brain activity! This information is combined with contextual cues from outside your body. So, when you see that the Doberman breaks loose from its owner, you can perceive that your heart begins to beat faster (an internal body signal). Then, your brain combines the external contextual cues (“the Doberman is loose!”) with your body signals, leading you to feel fear. Patients with damage to their insular regions are not so good at tracking their inner body signals and combining them with their emotions. The insula is critical for giving emotional value to an event.

Lastly, Figure 2 shows the temporal regions marked with orange. The temporal regions associate the object or person you are focusing on with the context. Memory plays a major role here. For instance, when the Doberman breaks loose, you look at his owner and realize that it is the kind man you met last week at the pet shop. Also, the temporal regions link contextual information with information from the frontal and insular regions. This system supports your knowledge that Dobermans can attack people, prompting you to seek protection.

To summarize, combining what you experience with the social context relies on a brain network that includes the frontal, insular, and temporal regions. Thanks to this network, we can interpret all sorts of social events. The frontal areas adjust and update what you think, feel, and do depending on present and past happenings. These areas also predict possible events in your surroundings. The insula combines signals from within and outside your body to produce a specific feeling. The temporal regions associate objects and persons with the current situation. So, all the parts of the social context network model work together to combine contextual information when you are in social settings.

When Context Cannot be Processed

Our model helps to explain findings from patients with brain damage. These patients have difficulties processing contextual cues. For instance, people with autism find it hard to make eye contact and interact with others. They may show repetitive behaviors (e.g., constantly lining up toy cars) or excessive interest in a topic. They may also behave inappropriately and have trouble adjusting to school, home, or work. People with autism may fail to recognize emotions in others’ faces. Their empathy may also be reduced. One of our studies [ 6 ] showed that these problems are linked to a decreased ability to process contextual information. Persons with autism and healthy subjects performed tasks involving different social skills. Autistic people did poorly in tasks that relied on contextual cues—for instance, detecting a person’s emotion based on his gestures or voice tone. But, autistic people did well in tasks that didn’t require analyzing context, for example tasks that could be completed by following very general rules (for example, “never touch a stranger on the street”). Thus, the social problems that we often see in autistic people might result from difficulty in processing contextual cues.

Another disease that may result from problems processing contextual information is called behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia . Patients with this disease exhibit changes in personality and in the way they interact with others, after about age 60. They may do improper things in public. Like people with autism, they may not show empathy or may not recognize emotions easily. Also, they find it hard to deal with the details of context needed to understand social events. All these changes may reflect general problems processing social context information. These problems may be caused by damage to the brain network described above.

Our model can also explain patients with damage to the frontal lobes or those who have conditions such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder [ 7 ]. Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by atypical social cognition and inability to distinguish between real and imagined world (as in the case of hallucinations). Similar but milder problems appear in patients with bipolar disorder, which is another psychiatric condition mainly characterized by oscillating periods of depression and periods of elevated mood (called hypomania or mania).

In sum, the problems with social behavior seen in many diseases are probably linked to poor context processing after damage to certain brain areas, as proposed by our model ( Figure 2 ). Future research should explore how correct this model is, adding more data about the processes and regions it describes.

New Techniques to Assess Social Behavior and Contextual Processing

The results mentioned above are important for scientists and doctors. However, they have a great limitation. They do not reflect how people behave in daily life! Most of the research findings came from tasks in a laboratory, in which a person responded to pictures or videos. These tasks do not really represent how we act every day in our lives. Social life is much more complicated than sitting at a desk and pressing buttons when you see images on a computer, right? Research based on such tasks doesn’t reflect real social situations. In daily life, people interact in contexts that constantly change.

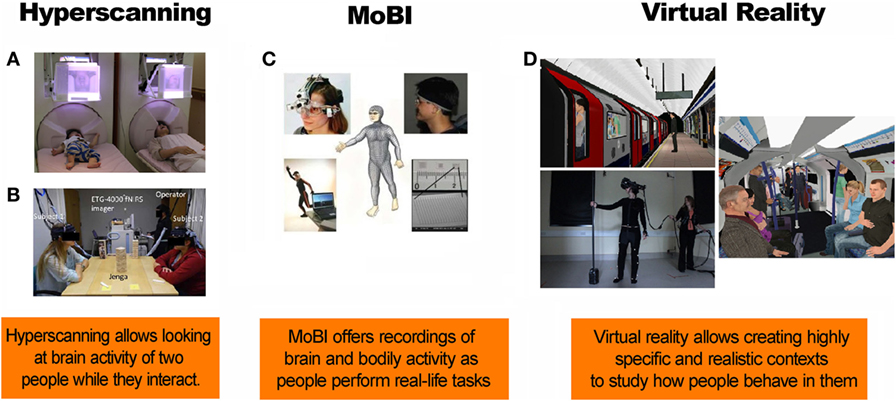

Fortunately, new methods allow scientists to assess real-life interactions. Hyperscanning is one of these methods. Hyperscanning allows measurement of the brain activity of two or more people while they perform activities together. For example, each subject can lie inside a separate scanner (a large tube containing powerful magnets). This scanner can detect changes in blood flow in the brain while the two people interact. This approach is used, for example, to study the brains of a mother and her child while they are looking at each other’s faces ( Figure 3A ).

- Figure 3 - New techniques to study processing of contextual cues.

- A. A mother and her infant look at each others’ facial expression while their brain activity is recorded (reproduced with permission from Masayuki et al. [ 8 ]). B. Hyperscanning of people interacting with each other during a game of Jenga (reproduced with permission from Liu et al. [ 9 ]). C. A new method of studying brain activity, called mobile brain/body imaging (MoBI) (reproduced with permission from Makeig et al. [ 10 ]). D. Virtual reality simulations of a virtual train at the station and a virtual train carriage (reproduced with permission from Freeman et al. [ 11 ]).

Hyperscanning can also be done using electroencephalogram equipment. Electroencephalography measures the electrical activity of the brain. Special sensors called electrodes are attached to the head. They are hooked by wires to a computer which records the brain’s electrical activity. Figure 3B shows an example of the use of electroencephalogram hyperscanning. This method has been used to measure the brain activity in two individuals while they are playing Jenga. Future research should apply this technique to study the processing of social contextual cues.

One limitation of hyperscanning is that it typically requires participants to remain still. However, real-life interactions involve many bodily actions. Fortunately, a new method called mobile brain/body imaging (MoBI, Figure 3C ) allows the measurement of brain activity and bodily actions while people interact in natural settings.

Another interesting approach is to use virtual reality . This technique involves fake situations. However, it puts people in different situations that require social interaction. This is closer to real life than the tasks used in most laboratories. As an example, consider Figure 3D . This shows a virtual reality experiment in which participants traveled through an underground tube station in London. Our understanding of the way context impacts social behavior could be expanded in future virtual reality studies.

In sum, future research should use new methods for measuring real-life interactions. This type of research could be very important for doctors to understand what happens to the processing of social context cues in various brain injuries or diseases. These realistic tasks are more sensitive than most of the laboratory tasks that are usually used for the assessment of patients with brain disorders.

Empathy : ↑ The ability to feel what another person is feeling, that is, to “place yourself in that person’s shoes.”

Autism : ↑ A general term for a group of complex disorders of brain development. These disorders are characterized by repetitive behaviors, as well as different levels of difficulty with social interaction and both verbal and non-verbal communications.

Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia : ↑ A brain disease characterized by progressive changes in personality and loss of empathy. Patients experience difficulty in regulating their behavior, and this often results in socially inappropriate actions. Patients typically start to show symptoms around age 60.

Hyperscanning : ↑ A novel technique to measure brain activity simultaneously from two people.

Virtual Reality : ↑ Computer technologies that use software to generate realistic images, sounds, and other sensations that replicate a real environment. This technique uses specialized display screens or projectors to simulate the user’s physical presence in this environment, enabling him or her to interact with the virtual space and any objects depicted there.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from CONICYT/FONDECYT Regular (1170010), FONDAP 15150012, and the INECO Foundation.

[1] ↑ Ibanez, A., and Manes, F. 2012. Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 78(17):1354–62. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182518375

[2] ↑ Chun, M. M. 2000. Contextual cueing of visual attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4(5):170–8. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01476-5

[3] ↑ Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., and Gendron, M. 2011. Context in emotion perception. Curr. Direct Psychol. Sci. 20(5):286–90. doi:10.1177/0963721411422522

[4] ↑ Beck, D. M., and Kastner, S. 2005. Stimulus context modulates competition in human extrastriate cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 8(8):1110–6. doi:10.1038/nn1501

[5] ↑ Bar, M. 2004. Visual objects in context. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5(8):617–29. doi:10.1038/nrn1476

[6] ↑ Baez, S., and Ibanez, A. 2014. The effects of context processing on social cognition impairments in adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Front. Neurosci. 8:270. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00270

[7] ↑ Baez, S, Garcia, A. M., and Ibanez, A. 2016. The Social Context Network Model in psychiatric and neurological diseases. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 30:379–96. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_443

[8] ↑ Masayuki, H., Takashi, I., Mitsuru, K., Tomoya, K., Hirotoshi, H., Yuko, Y., and Minoru, A. 2014. Hyperscanning MEG for understanding mother-child cerebral interactions. Front Hum Neurosci 8:118. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00118

[9] ↑ Liu, N., Mok, C., Witt, E. E., Pradhan, A. H., Chen, J. E., and Reiss, A. L. 2016. NIRS-based hyperscanning reveals inter-brain neural synchronization during cooperative Jenga game with face-to-face communication. Front Hum Neurosci 10:82. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00082

[10] ↑ Makeig, S., Gramann, K., Jung, T.-P., Sejnowski, T. J., and Poizner, H. 2009. Linking brain, mind and behavior: The promise of mobile brain/body imaging (MoBI). Int J Psychophys 73:985–1000

[11] ↑ Evans, N., Lister, R., Antley, A., Dunn, G., and Slater, M. 2014. Height, social comparison, and paranoia: An immersive virtual reality experimental study. Psych Res 218(3):348–52. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.014

Doc’s Things and Stuff

social context | Definition

Social context refers to the environment of people, relationships, and culture that surrounds and influences an individual’s behavior and experiences.

Understanding Social Context

Definition and importance.

Social context is the setting in which social interactions occur, encompassing the cultural, economic, political, and social conditions that influence people’s lives. It plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions. Understanding social context helps explain why people act the way they do and how various factors influence human behavior.

Elements of Social Context

Cultural norms and values.

Cultural norms and values are the shared beliefs and practices that guide behavior within a society. These norms and values shape how individuals interact with each other and understand the world. For example, cultural norms around family structure, work ethic, and social roles influence how people behave and make decisions.

Social Structures

Social structures refer to the organized patterns of relationships and institutions that make up society. These include family, education systems, religious institutions, and economic systems. Social structures provide a framework for social behavior and influence individuals’ opportunities and constraints.

Social Roles and Status

Social roles are the expected behaviors associated with particular positions in society, such as being a student, parent, or employee. Social status refers to the prestige or social value assigned to these roles. Both roles and status influence how individuals interact with others and navigate their social world. For example, a person’s status as a doctor may command respect and influence their interactions with patients and colleagues.

Economic Conditions

Economic conditions, such as wealth distribution, employment rates, and access to resources, significantly impact social context. Economic stability or instability can influence individuals’ stress levels, opportunities for education and employment, and overall quality of life. For instance, economic downturns often lead to increased job insecurity and can affect family dynamics and mental health.

Political Environment

The political environment includes the laws, policies, and government structures that regulate society. Political conditions can affect individuals’ rights, access to services, and participation in civic life. For example, policies on healthcare, education, and immigration directly impact people’s lives and social interactions.

The Role of Social Context in Shaping Behavior

Influence on identity.

Social context plays a vital role in shaping individual identity. Through interactions with family, peers, and broader society, people develop their sense of self and their place in the world. For example, a person’s cultural background, social class, and community can influence their values, aspirations, and self-perception.

Behavior and Decision-Making

Individuals make decisions and behave in ways that are influenced by their social context. For example, peer pressure can affect teenagers’ choices, such as engaging in risky behaviors or conforming to group norms. Similarly, cultural expectations around gender roles can influence career choices and family dynamics.

Socialization Process

Socialization is the process by which individuals learn and internalize the norms, values, and behaviors appropriate to their society. This process occurs throughout life, beginning in childhood and continuing through adulthood. Social institutions like family, schools, and media play significant roles in socialization, transmitting cultural norms and expectations.

Social Context and Social Change

Impact of social movements.

Social movements can challenge and change the existing social context. Movements for civil rights, gender equality, and environmental sustainability have reshaped societal norms and policies. For example, the women’s rights movement has significantly altered norms around gender roles and workplace equality.

Technological Advancements

Technological advancements can also transform social context by changing how people communicate, work, and access information. The rise of social media, for instance, has created new forms of social interaction and influenced cultural norms around communication and self-presentation.

Challenges and Opportunities

Navigating diverse social contexts.

In increasingly multicultural societies, individuals often navigate multiple social contexts simultaneously. This can create challenges in balancing different cultural expectations and norms. However, it also presents opportunities for learning, growth, and greater cultural understanding.

Addressing Social Inequality

Understanding social context is crucial for addressing social inequalities. By recognizing how factors like economic conditions, social structures, and cultural norms contribute to disparities, policymakers and activists can develop more effective strategies for promoting social justice and equity.

Social context is a multifaceted concept that encompasses the various environments influencing individuals’ behaviors, attitudes, and experiences. By examining the elements and impacts of social context, we gain a deeper understanding of human behavior and the complex interplay of social forces. This understanding is essential for fostering more inclusive and equitable societies.

References and Further Reading

- Dornbusch, S. M. (1989). The sociology of adolescence . Annual review of sociology , 15 (1), 233-259.

On This Site

- Fundamentals of Sociology

This work is licensed under an Open Educational Resource-Quality Master Source (OER-QMS) License .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Social Context

‘Social Context’ refers to the immediate physical and social setting in which people live or in which something happens or develops. This includes the culture that the individual was educated or lives in, and the people and institutions with whom they interact. Social context influences and, to some extent, determines thought, feeling, and action. It ranges from a brief interaction with a stranger to broad societal and cultural forces.

Understanding Social Context

To grasp the concept of social context, we must delve into its components and the influence it exerts on individuals and societies.

Social context can be broken down into various elements, including cultural norms, social structures (like family or community), and the specific situation in which an individual finds themselves.

Influence on Behavior and Perceptions

Social context significantly impacts individual behavior, perceptions, and interactions. It can shape an individual’s values, beliefs, and expectations.

The Role in Different Fields

Social context plays a pivotal role across various disciplines, from psychology to sociology and beyond.

In Psychology

In psychology, social context is used to understand individual behavior in social situations and the influences of societal norms and structures.

In Sociology

Sociologists study social context to comprehend societal patterns, trends, and structures, helping them understand social phenomena and changes over time.

Understanding the social context offers valuable insights into various aspects of life and society.

Enhances Communication

By understanding the social context of a situation, we can communicate more effectively, considering cultural norms, values, and expectations.

Guides Policy and Decision-Making

Social context is crucial in informing policy-making, ensuring that decisions consider societal norms, values, and structures.

To further illuminate the concept, let’s consider some examples of social context.

Example 1: Educational Settings

The social context of a classroom— including its cultural norms, student-teacher dynamics, and broader school environment— can influence students’ learning and engagement.

Example 2: Online Communities

Online communities, like those on social media platforms, have their unique social contexts that impact user behavior, interactions, and content creation.

Recognizing and Analyzing Social Context

Being able to recognize and analyze social context is a valuable skill. Here are some tips to help.

Be Observant

Pay attention to the physical and social environment, the individuals involved, and the cultural and societal norms at play.

Keep an Open Mind

Maintain an open mind and be sensitive to cultural differences, acknowledging that social context can differ greatly between societies and groups.

In essence, social context is a crucial factor that shapes our behaviors, interactions, perceptions, and the world around us. By understanding and considering social context, we can communicate more effectively, make informed decisions, and appreciate the complexity and diversity of human societies.

Social Psychology: Definition, Theories, Scope, & Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Social psychology is the scientific study of how people’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, intentions, and goals are constructed within a social context by the actual or imagined interactions with others.

It, therefore, looks at human behavior as influenced by other people and the conditions under which social behavior and feelings occur.

Baron, Byrne, and Suls (1989) define social psychology as “the scientific field that seeks to understand the nature and causes of individual behavior in social situations” (p. 6).

Topics examined in social psychology include the self-concept , social cognition, attribution theory , social influence, group processes, prejudice and discrimination , interpersonal processes, aggression, attitudes , and stereotypes .

Social psychology operates on several foundational assumptions. These fundamental beliefs provide a framework for theories, research, and interpretations.

- Individual and Society Interplay : Social psychologists assume an interplay exists between individual minds and the broader social context. An individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are continuously shaped by social interactions, and in turn, individuals influence the societies they are a part of.

- Behavior is Contextual : One core assumption is that behavior can vary significantly based on the situation or context. While personal traits and dispositions matter, the circumstances or social environment often play a decisive role in determining behavior.

- Objective Reality is Difficult to Attain : Our perceptions of reality are influenced by personal beliefs, societal norms, and past experiences. Therefore, our understanding of “reality” is subjective and can be biased or distorted.

- Social Reality is Constructed : Social psychologists believe that individuals actively construct their social world . Through processes like social categorization, attribution, and cognitive biases, people create their understanding of others and societal norms.

- People are Social Beings with a Need to Belong : A fundamental assumption is the inherent social nature of humans. People have an innate need to connect with others, form relationships, and belong to groups. This need influences a wide range of behaviors and emotions.

- Attitudes Influence Behavior : While this might seem straightforward, it’s a foundational belief that our attitudes (combinations of beliefs and feelings) can and often do drive our actions. However, it’s also understood that this relationship can be complex and bidirectional.

- People Desire Cognitive Consistency : This is the belief that people are motivated to maintain consistency in their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Cognitive dissonance theory , which posits that people feel discomfort when holding conflicting beliefs and are motivated to resolve this, is based on this assumption.

- People are Motivated to See Themselves in a Positive Light : The self plays a central role in social psychology. It’s assumed that individuals are generally motivated to maintain and enhance a positive self-view.

- Behavior Can be Predicted and Understood : An underlying assumption of any science, including social psychology, is that phenomena (in this case, human behavior in social contexts) can be studied, understood, predicted, and potentially influenced.

- Cultural and Biological Factors are Integral : Though earlier social psychology might have been criticized for neglecting these factors, contemporary social psychology acknowledges the roles of both biology (genes, hormones, brain processes) and culture (norms, values, traditions) in shaping social behavior.

Early Influences

Aristotle believed that humans were naturally sociable, a necessity that allows us to live together (an individual-centered approach), whilst Plato felt that the state controlled the individual and encouraged social responsibility through social context (a socio-centered approach).

Hegel (1770–1831) introduced the concept that society has inevitable links with the development of the social mind. This led to the idea of a group mind, which is important in the study of social psychology.

Lazarus & Steinthal wrote about Anglo-European influences in 1860. “Volkerpsychologie” emerged, which focused on the idea of a collective mind.

It emphasized the notion that personality develops because of cultural and community influences, especially through language, which is both a social product of the community as well as a means of encouraging particular social thought in the individual. Therefore Wundt (1900–1920) encouraged the methodological study of language and its influence on the social being.

Early Texts

Texts focusing on social psychology first emerged in the 20th century. McDougall published the first notable book in English in 1908 (An Introduction to Social Psychology), which included chapters on emotion and sentiment, morality, character, and religion, quite different from those incorporated in the field today.

He believed social behavior was innate/instinctive and, therefore, individual, hence his choice of topics. This belief is not the principle upheld in modern social psychology, however.

Allport’s work (1924) underpins current thinking to a greater degree, as he acknowledged that social behavior results from interactions between people.

He also took a methodological approach, discussing actual research and emphasizing that the field was a “science … which studies the behavior of the individual in so far as his behavior stimulates other individuals, or is itself a reaction to this behavior” (1942: p. 12).

His book also dealt with topics still evident today, such as emotion, conformity, and the effects of an audience on others.

Murchison (1935) published The first handbook on social psychology was published by Murchison in 1935. Murphy & Murphy (1931/37) produced a book summarizing the findings of 1,000 studies in social psychology. A text by Klineberg (1940) looked at the interaction between social context and personality development. By the 1950s, several texts were available on the subject.

Journal Development

• 1950s – Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology

• 1963 – Journal of Personality, British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology

• 1965 – Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

• 1971 – Journal of Applied Social Psychology, European Journal of Social Psychology

• 1975 – Social Psychology Quarterly, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

• 1982 – Social Cognition

• 1984 – Journal of Social and Personal Relationships

Early Experiments

There is some disagreement about the first true experiment, but the following are certainly among some of the most important.

Triplett (1898) applied the experimental method to investigate the performance of cyclists and schoolchildren on how the presence of others influences overall performance – thus, how individuals are affected and behave in the social context.

By 1935, the study of social norms had developed, looking at how individuals behave according to the rules of society. This was conducted by Sherif (1935).

Lewin et al. then began experimental research into leadership and group processes by 1939, looking at effective work ethics under different leadership styles.

Later Developments

Much of the key research in social psychology developed following World War II, when people became interested in the behavior of individuals when grouped together and in social situations. Key studies were carried out in several areas.

Some studies focused on how attitudes are formed, changed by the social context, and measured to ascertain whether a change has occurred.

Amongst some of the most famous works in social psychology is that on obedience conducted by Milgram in his “electric shock” study, which looked at the role an authority figure plays in shaping behavior. Similarly, Zimbardo’s prison simulation notably demonstrated conformity to given roles in the social world.

Wider topics then began to emerge, such as social perception, aggression, relationships, decision-making, pro-social behavior, and attribution, many of which are central to today’s topics and will be discussed throughout this website.

Thus, the growth years of social psychology occurred during the decades following the 1940s.

The scope of social psychology is vast, reflecting the myriad ways social factors intertwine with individual cognition and behavior.

Its principles and findings resonate in virtually every area of human interaction, making it a vital field for understanding and improving the human experience.

- Interpersonal Relationships : This covers attraction, love, jealousy, friendship, and group dynamics. Understanding how and why relationships form and the factors that contribute to their maintenance or dissolution is central to this domain.

- Attitude Formation and Change : How do individuals form opinions and attitudes? What methods can effectively change them? This scope includes the study of persuasion, propaganda, and cognitive dissonance.

- Social Cognition : This examines how people process, store, and apply information about others. Areas include social perception, heuristics, stereotypes, and attribution theories.

- Social Influence : The study of conformity, compliance, obedience, and the myriad ways individuals influence one another falls within this domain.

- Group Dynamics : This entails studying group behavior, intergroup relations, group decision-making processes, leadership, and more. Concepts like groupthink and group polarization emerge from this area.

- Prejudice and Discrimination : Understanding the roots of bias, racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice, as well as exploring interventions to reduce them, is a significant focus.

- Self and Identity : Investigating self-concept, self-esteem, self-presentation, and the social construction of identity are all part of this realm.

- Prosocial Behavior and Altruism : Why do individuals sometimes help others, even at a cost to themselves? This area delves into the motivations and conditions that foster cooperative and altruistic behavior.

- Aggression : From understanding the underlying causes of aggressive behavior to studying societal factors that exacerbate or mitigate aggression, this topic seeks to dissect the nature of hostile actions.

- Cultural and Cross-cultural Dimensions : As societies become more interconnected, understanding cultural influences on behavior, cognition, and emotion is crucial. This area compares and contrasts behaviors across different cultures and societal groups.

- Environmental and Applied Settings : Social psychology principles find application in health psychology, environmental behavior, organizational behavior, consumer behavior, and more.

- Social Issues : Social psychologists might study the impact of societal structures on individual behavior, exploring topics like poverty, urban stress, and crime.

- Education : Principles of social psychology enhance teaching methods, address issues of classroom dynamics, and promote effective learning.

- Media and Technology : In the digital age, understanding the effects of media consumption, the dynamics of online communication, and the formation of online communities is increasingly relevant.

- Law : Insights from social psychology inform areas such as jury decision-making, eyewitness testimony, and legal procedures.

- Health : Concepts from social psychology are employed to promote health behaviors, understand doctor-patient dynamics, and tackle issues like addiction.

Example Theories

Allport (1920) – social facilitation.

Allport introduced the notion that the presence of others (the social group) can facilitate certain behavior.

It was found that an audience would improve an actor’s performance in well-learned/easy tasks but leads to a decrease in performance on newly learned/difficult tasks due to social inhibition.

Bandura (1963) Social Learning Theory

Bandura introduced the notion that behavior in the social world could be modeled. Three groups of children watched a video where an adult was aggressive towards a ‘bobo doll,’ and the adult was either just seen to be doing this, was rewarded by another adult for their behavior, or was punished for it.

Children who had seen the adult rewarded were found to be more likely to copy such behavior.

Festinger (1950) – Cognitive Dissonance

Festinger, Schacter, and Black brought up the idea that when we hold beliefs, attitudes, or cognitions which are different, then we experience dissonance – this is an inconsistency that causes discomfort.

We are motivated to reduce this by either changing one of our thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes or selectively attending to information that supports one of our beliefs and ignores the other (selective exposure hypothesis).

Dissonance occurs when there are difficult choices or decisions or when people participate in behavior that is contrary to their attitude. Dissonance is thus brought about by effort justification (when aiming to reach a modest goal), induced compliance (when people are forced to comply contrary to their attitude), and free choice (when weighing up decisions).

Tajfel (1971) – Social Identity Theory

When divided into artificial (minimal) groups, prejudice results simply from the awareness that there is an “out-group” (the other group).

When the boys were asked to allocate points to others (which might be converted into rewards) who were either part of their own group or the out-group, they displayed a strong in-group preference. That is, they allocated more points on the set task to boys who they believed to be in the same group as themselves.

This can be accounted for by Tajfel & Turner’s social identity theory, which states that individuals need to maintain a positive sense of personal and social identity: this is partly achieved by emphasizing the desirability of one’s own group, focusing on distinctions between other “lesser” groups.

Weiner (1986) – Attribution Theory

Weiner was interested in the attributions made for experiences of success and failure and introduced the idea that we look for explanations of behavior in the social world.

He believed that these were made based on three areas: locus, which could be internal or external; stability, which is whether the cause is stable or changes over time: and controllability.

Milgram (1963) – Shock Experiment

Participants were told that they were taking part in a study on learning but always acted as the teacher when they were then responsible for going over paired associate learning tasks.

When the learner (a stooge) got the answer wrong, they were told by a scientist that they had to deliver an electric shock. This did not actually happen, although the participant was unaware of this as they had themselves a sample (real!) shock at the start of the experiment.

They were encouraged to increase the voltage given after each incorrect answer up to a maximum voltage, and it was found that all participants gave shocks up to 300v, with 65 percent reaching the highest level of 450v.

It seems that obedience is most likely to occur in an unfamiliar environment and in the presence of an authority figure, especially when covert pressure is put upon people to obey. It is also possible that it occurs because the participant felt that someone other than themselves was responsible for their actions.

Haney, Banks, Zimbardo (1973) – Stanford Prison Experiment

Volunteers took part in a simulation where they were randomly assigned the role of a prisoner or guard and taken to a converted university basement resembling a prison environment. There was some basic loss of rights for the prisoners, who were unexpectedly arrested, and given a uniform and an identification number (they were therefore deindividuated).

The study showed that conformity to social roles occurred as part of the social interaction, as both groups displayed more negative emotions, and hostility and dehumanization became apparent.

Prisoners became passive, whilst the guards assumed an active, brutal, and dominant role. Although normative and informational social influence played a role here, deindividuation/the loss of a sense of identity seemed most likely to lead to conformity.

Both this and Milgram’s study introduced the notion of social influence and the ways in which this could be observed/tested.

Provides Clear Predictions

As a scientific discipline, social psychology prioritizes formulating clear and testable hypotheses. This clarity facilitates empirical testing, ensuring the field’s findings are based on observable and quantifiable phenomena.

The Asch conformity experiments hypothesized that individuals would conform to a group’s incorrect judgment.

The clear prediction allowed for controlled experimentation to determine the extent and conditions of such conformity.

Emphasizes Objective Measurement

Social psychology leans heavily on empirical methods, emphasizing objectivity. This means that results are less influenced by biases or subjective interpretations.

Double-blind procedures , controlled settings, and standardized measures in many social psychology experiments ensure that results are replicable and less prone to experimenter bias.

Empirical Evidence

Over the years, a multitude of experiments in social psychology have bolstered the credibility of its theories. This experimental validation lends weight to its findings and claims.

The robust body of experimental evidence supporting cognitive dissonance theory, from Festinger’s initial studies to more recent replications, showcases the theory’s enduring strength and relevance.

Limitations

Underestimates individual differences.

While social psychology often looks at broad trends and general behaviors, it can sometimes gloss over individual differences.

Not everyone conforms, obeys, or reacts in the same way, and these nuanced differences can be critical.

While Milgram’s obedience experiments showcased a startling rate of compliance to authority, there were still participants who resisted, and their reasons and characteristics are equally important to understand.

Ignores Biology

While social psychology focuses on the social environment’s impact on behavior, early theories sometimes neglect the biological underpinnings that play a role.

Hormones, genetics, and neurological factors can influence behavior and might intersect with social factors in complex ways.

The role of testosterone in aggressive behavior is a clear instance where biology intersects with the social. Ignoring such biological components can lead to an incomplete understanding.

Superficial Snapshots of Social Processes

Social psychology sometimes offers a narrow view, capturing only a momentary slice of a broader, evolving process. This might mean that the field fails to capture the depth, evolution, or intricacies of social processes over time.

A study might capture attitudes towards a social issue at a single point in time, but not account for the historical evolution, future shifts, or deeper societal underpinnings of those attitudes.

Allport, F. H. (1920). The influence of the group upon association and thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 3(3), 159.

Allport, F. H. (1924). Response to social stimulation in the group. Social psychology , 260-291.

Allport, F. H. (1942). Methods in the study of collective action phenomena. The Journal of Social Psychology , 15(1), 165-185.

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67(6), 601.

Baron, R. A., Byrne, D., & Suls, J. (1989). Attitudes: Evaluating the social world. Baron et al, Social Psychology . 3rd edn. MA: Allyn and Bacon, 79-101.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social processes in informal groups .

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews , 9(1-17).

Klineberg, O. (1940). The problem of personality .

Krewer, B., & Jahoda, G. (1860). On the scope of Lazarus and Steinthals “Völkerpsychologie” as reflected in the. Zeitschrift für Völkerpsychologie und Sprachwissenschaft, 1890, 4-12.

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R., & White, R. K. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created “social climates”. The Journal of Social Psychology , 10(2), 269-299.

Mcdougall, W. (1908). An introduction to social psychology . Londres: Methuen.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67(4), 371.

Murchison, C. (1935). A handbook of social psychology .

Murphy, G., & Murphy, L. B. (1931). Experimental social psychology .

Sherif, M. (1935). A study of some social factors in perception. Archives of Psychology (Columbia University).

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behavior. European journal of social psychology , 1(2), 149-178.

Triplett, N. (1898). The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American journal of Psychology , 9(4), 507-533.

Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion . New York: Springer-Verlag.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Decision-Making Processes in Social Contexts

Elizabeth bruch, fred feinberg.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Please direct correspondence to Elizabeth Bruch at: 500 S. State Street, Department of Sociology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104

Issue date 2017 Jul.

Over the past half-century, scholars in the interdisciplinary field of Judgment and Decision Making have amassed a trove of findings, theories, and prescriptions regarding the processes ordinary people enact when making choices. But this body of knowledge has had little influence on sociology. Sociological research on choice emphasizes how features of the social environment shape individual behavior, not people’s underlying decision processes. Our aim in this article is to provide an overview of selected ideas, models, and data sources from decision research that can fuel new lines of inquiry on how socially situated actors navigate both everyday and major life choices. We also highlight opportunities and challenges for cross-fertilization between sociology and decision research that can allow the methods, findings, and contexts of each field to expand their joint range of inquiry.

Keywords: heuristics, decision making, micro-sociology, discrete choice

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, there has been an explosion of interest in, and recognition of the importance of, how people make decisions. From Daniel Kahneman’s 2002 Nobel Prize for his work on “Heuristics and Biases,” to the rise in prominence of Behavioral Economics, to the burgeoning policy applications of behavioral “nudges” ( Kahneman 2003 ; Camerer & Loewenstein 2004 ; Shafir 2013 ), both scholars and policy makers increasingly focus on choice processes as a key domain of research and intervention. Researchers in the interdisciplinary field of Judgment and Decision Making (JDM)—which primarily comprises cognitive science, behavioral economics, academic marketing, and organizational behavior—have generated a wealth of findings, insights, and prescriptions regarding how people make choices. In addition, with the advent of rich observational data from purchase histories, a related line of work has revolutionized statistical models of decision making that aim to represent underlying choice process.

But for the most part these models and ideas have not penetrated sociology. 1 We believe there are several reasons for this. First, JDM research has largely been focused on contrasting how a fully informed, computationally unlimited (i.e., “rational”) person would behave to how people actually behave, and pointing out systematic deviations from this normative model ( Loewenstein 2001 ). Since sociology never fully embraced the rational choice model of behavior, debunking it is less of a disciplinary priority. 2 Second, JDM research is best known for its focus on problems that involve risk , where the outcome is probabilistic and the payoff probabilities are known ( Kahneman & Tversky 1979 , 1982 , 1984 ), and ambiguity , where the outcome is probabilistic and the decision-maker does not have complete information on payoff probabilities ( Ellsberg 1961 ; Einhorn & Hogarth 1988 ; Camerer & Weber 1992 ). In both these cases, there is an optimal choice to be made, and the research explores how people’s choices deviate from that answer. But most sociological problems—such as choosing a romantic partner, neighborhood, or college—are characterized by obscurity : there is no single, obvious, optimal, or correct answer.

Perhaps most critically, the JDM literature has by and large minimized the role of social context in decision processes. This is deliberate. Most experiments performed by psychologists are designed to isolate processes that can be connected with features of decision tasks or brain functioning; it is incumbent on researchers working in this tradition to “de-socialize” the environment and reduce it to a single aspect or theoretically predicted confluence of factors. Although there is a rich body of work on how heuristics are matched to particular decision environments ( Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier 2011 ), these environments are by necessity often highly stylized laboratory constructs aimed at exerting control over key features of the environment. 3 This line of work intentionally de-emphasizes or eliminates aspects of realistic social environments, which limits its obvious relevance for sociologists.

Finally, there is the challenge of data availability: sociologists typically do not observe the intermediate stages by which people arrive at decision outcomes. For example, researchers can fairly easily determine what college a person attended, what job they chose, or whom they married, but they rarely observe how they got to that decision—that is, how people learned about and evaluated available options, and which options were excluded either because they were infeasible or unacceptable. But such process data can be collected in a number of different ways, as detailed later in this article. Moreover, opportunities to study sociologically relevant decision processes are rapidly expanding, owing to the advent of disintermediated sources like the Internet and smart phones, which allow researchers to observe human behavior at a much finer level of temporal and geographic granularity than ever before. Equally important, these data often contain information on which options people considered , but ultimately decided against. Such activity data provide a rich source of information on sociologically relevant decision processes ( Bruch et al. 2016 ).

We believe that the time is ripe for a new line of work that draws on insights from cognitive science and decision theory to examine choice processes and how they play out in social environments. As we discuss in the next section, sociology and decision research offer complementary perspectives on decision-making and there is much to be gained from combining them. One benefit of this union is that it can deepen sociologists’ understanding of how and why individual outcomes differ across contexts. By leveraging insights on how contextual factors and aspects of choice problems influence decision strategies, sociologists can better pinpoint how, why, and when features of the social environment trigger and shape human behavior. This also presents a unique opportunity for cross-fertilization. While sociologists can draw from the choice literature’s rich understanding of and suite of tools to probe decision processes, work on decision-making can also benefit from sociologists’ insights into how social context enables or constrains behavior.

The literature on judgment and decision-making is enormous; our goal here is to offer a curated introduction aimed at social scientists new to this area. In addition to citing recent studies, we deliberately reference the classic and integrative literature in this field so that researchers can acquaint themselves with the works that introduced these ideas, and gain a comfortable overview to it. We highlight empirical studies of decision making that help address how people make critical life decisions, such as choosing a neighborhood, college, life partner, or occupation. Thus, our focus is on research that is relevant for understanding decision processes characterized by obscurity, where there is no obvious correct or optimal answer. Due to its selective nature, our review does not include a discussion of several major areas of the JDM literature, most notably Prospect Theory, which focuses on how people can distort both probabilities and outcome values when these are known (to the researcher) with certainty; we also do not discuss the wide range of anomalies documented in human cognition, for example mental accounting, the endowment effect, and biases such as availability or anchoring ( Tversky & Kahneman 1973 ; Kahneman & Tversky 1973 , 1981 ; Kahneman et al. 1991 ).

The balance of the article is as follows. We first explain how decision research emerged as a critique of rational choice theory, and show how these models of behavior complement existing work on action and decision-making in sociology. The core of the paper provides an overview of how cognitive, emotional, and contextual factors shape decision processes. We then introduce the data and methods commonly used to study choice processes. Decision research relies on a variety of data sources, including results from lab and field experiments, surveys, brain scans, and observations of in-store shopping and other behavior. We discuss their relative merits, and provide a brief introduction to statistical modeling approaches. We close with some thoughts about opportunities and challenges for sociologists wanting to incorporate insights and methods from the decision literature into their research programs.

SOCIOLOGICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSEPCTIVES ON DECISION PROCESSES

To understand how sociology and psychology offer distinct but complementary views of decision processes, we begin with a brief introduction to the dominant model of human decision-making in the social sciences: rational choice theory. This model, endemic to neoclassical economic analyses, has permeated into many fields including sociology, anthropology, political science, philosophy, history, and law ( Coleman 1991 ; Gely & Spiller 1990 ; Satz & Ferejohn 1994 ; Levy 1997 ). In its classic form, the rational choice model of behavior assumes that decision makers have full knowledge of the relevant aspects of their environment, a stable set of preferences for evaluating choice alternatives, and unlimited skill in computation ( Samuelson 1947 ; Von Neumann & Morgenstern 2007 ; Becker 1993 ). Actors are assumed to have a complete inventory of possible alternatives of action; there is no allowance for focus of attention or a search for new alternatives ( Simon 1991 , p. 4). Indeed, a distinguishing feature of the classic model is its lack of attention to the process of decision-making. Preference maximization is a synonym for choice ( McFadden 2001 , p. 77).

Rational choice has a long tradition in sociology, but its popularity increased in the 1980s and 1990s, partly as a response to concern within sociology about the growing gap between social theory and quantitative empirical research ( Coleman 1986 ). Quantitative data analysis, despite focusing primarily on individual-level outcomes, is typically conducted without any reference to—let alone a model of—individual action ( Goldthorpe 1996 ; Esser 1996 ). Rational choice provides a theory of action that can anchor empirical research in meaningful descriptions of individuals’ behavior ( Hedström & Swedberg 1996 ). Importantly, the choice behavior of rational actors can also be straightforwardly implemented in regression-based models readily available in statistical software packages. Indeed while some scholars explicitly embrace rational choice as a model of behavior ( Hechter and Kanazawa 1997 ; Kroneberg and Kalter 2012 ), many others implicitly adopt it in their quantitative models of individual behavior.

Beyond Rational Choice

Sociologists have critiqued and extended the classical rational choice model in a number of ways. They have observed that people are not always selfish actors who behave in their own best interests ( England 1989 ; Margolis 1982 ), that preferences are not fixed characteristics of individuals ( Lindenberg and Frey 1993 ; Munch 1992 ), and that individuals do not always behave in ways that are purposive or optimal ( Somers 1989 ; Vaughan 1998 ). Most relevant to this article, sociologists have argued that the focus in classical rational choice on the individual as the primary unit of decision-making represents a fundamentally asocial representation of behavior. In moving beyond rational choice, theories of decision-making in sociology highlight the importance of social interactions and relationships in shaping behavior ( Pescosolido 1992 ; Emirbayer 1997 ). A large body of empirical work reveals how social context shapes people’s behavior across a wide range of domains, from neighborhood and school choice to decisions about friendship and intimacy to choices about eating, drinking, and other health-related behaviors ( Carrillo et al. 2016 ; Perna and Titus 2005 ; Small 2009 ; Pachucki et al. 2011 ; Rosenquist et al. 2010 ).

But This focus on social environments and social interactions has inevitably led to less attention being paid to the individual-level processes that underlie decision-making. In contrast, psychologists and decision theorists aiming to move beyond rational choice have focused their attention squarely on how individuals make decisions. In doing so, they have amassed several decades of work showing that the rational choice model is a poor representation of this process. 4 Their fundamental critique is that decision-making, as envisioned in the rational choice paradigm, would make overwhelming demands on our capacity to process information ( Bettman 1979 ; Miller 1956 ; Payne 1976 ). Decision-makers have limited time for learning about choice alternatives, limited working memory, and limited computational capabilities ( Miller 1956 ; Payne et al. 1993) As a result, they use heuristics that keep the information-processing demands of a task within the bounds of their limited cognitive capacity. 5 It is now widely recognized that the central process in human problem solving is to apply heuristics that carry out highly selective navigations of problem spaces ( Newell & Simon 1972 ).

However, in their efforts to zero in on the strategies people use to gather and process information, psychological studies of decision-making have focused largely on individuals in isolation. Thus, sociological and psychological perspectives on choice are complementary in that they each emphasize a feature of decision-making that the other field has left largely undeveloped. For this reason, and as we articulate further in the conclusion, we believe there is great potential for cross-fertilization between these areas of research. Because our central aim is to introduce sociologists to the JDM literature, we do not provide an exhaustive discussion of sociological work relevant to understanding decision processes. Rather, we highlight studies that illustrate the fruitful connections between sociological concerns and JDM research.

In the next sections, we discuss the role of different factors—cognitive, emotional, and contextual—in heuristic decision processes.

THE ROLE OF COGNITIVE FACTORS IN DECISION PROCESSES

There are two major challenges in processing decision-related information: first, each choice is typically characterized by multiple attributes, and no alternative is optimal on all dimensions; and, second, more than a tiny handful of information can overwhelm the cognitive capacity of decision makers ( Cowan 2010 ). Consider the problem of choosing among three competing job offers. Job 1 has high salary, but a moderate commuting time and a family-unfriendly workplace. Job 2 offers a low salary, but has a family-friendly workplace and short commuting time. Job 3 has a family-friendly workplace but a moderate salary and long commuting time. This choice would be easy if one alternative clearly dominated on all attributes. But, as is often the case, they all involve making tradeoffs and require the decision maker to weigh the relative importance of each attribute. Now imagine that, instead of three choices, there were ten, a hundred, or even a thousand potential alternatives. This illustrates the cognitive challenge faced by people trying to decide among neighborhoods, potential romantic partners, job opportunities, or health care plans.

We focus in this section on choices that involve deliberation, for example deciding where to live, what major to pursue in college, or what jobs to apply for. 6 (This is in contrast to decisions that are made more spontaneously, such as the choice to disclose personal information to a confidant [ Small & Sukhu 2016 ].) Commencing with the pioneering work of Howard & Sheth (1969) , scholars have accumulated substantial empirical evidence for the idea that such decisions are typically made sequentially , with each stage reducing the set of potential options ( Swait 1984 ; Roberts & Lattin 1991 , 1997 ). For a given individual, the set of potential options can first be divided into the set that he or she knows about, and those of which he or she is unaware. This “awareness set” is further divided into options the person would consider, and those that are irrelevant or unattainable. This smaller set is referred to as the consideration set , and the final decision is restricted to options within that set.

Research in consumer behavior suggests that the decision to include certain alternatives in the consideration set can be based on markedly different heuristics and criteria than the final choice decision (e.g., Payne 1976 ; Bettman & Park 1980 ; Salisbury & Feinberg 2012 ). In many cases, people use simple rules to restrict the energy involved in searching for options, or to eliminate options from future consideration. For example, a high school student applying to college may only consider schools within commuting distance of home, or schools where someone she knows has attended. Essentially, people favor less cognitively taxing rules that use a small number of choice attributes earlier in the decision process to eliminate almost all potential alternatives, but take into account a wider range of choice attributes when evaluating the few remaining alternatives for the final decision ( Liu & Dukes 2013 ).

Once the decision maker has narrowed down his or her options, the final choice decision may allow different dimensions of alternatives to be compensatory; in other words, a less attractive value on one attribute may be offset by a more attractive value on another attribute. However, a large body of decision research demonstrates that strategies to screen potential options for consideration are non-compensatory ; a decision-maker’s choice to eliminate from or include for consideration based on one attribute will not be compensated by the value of other attributes. In other words, compensatory decision rules are “continuous,” while non-compensatory decision rules are discontinuous or threshold ( Swait 2001 ; Gilbride & Allenby 2004 ).

Compensatory Decision Rules

The implicit decision rule used in statistical models of individual choice and the normative decision rule for rational choice is the weighted additive rule. Under this choice regime, decision-makers compute a weighted sum of all relevant attributes of potential alternatives. Choosers develop an overall assessment of each choice alternative by multiplying the attribute weight by the attribute level (for each salient attribute), and then sum over all attributes. This produces a single utility value for each alternative. The alternative with the highest value is selected, by assumption. Any conflict in values is assumed to be confronted and resolved by explicitly considering the extent to which one is willing to trade off attribute values, as reflected by the relative importance or beta coefficients ( Payne et al. 1993 , p. 24). Using this rule involves substantial computational effort and processing of information.

A simpler compensatory decision rule is the tallying rule, known to most of us as a “pro and con” list ( Alba & Marmorstein 1987 ). This strategy ignores information about the relative importance of each attribute. To implement this heuristic, a decision maker decides which attribute values are desirable or undesirable. Then she counts up the number desirable versus undesirable attributes. Strictly speaking, this rule forces people to make trade-offs among different attributes. However, it is less cognitively demanding than the weighted additive rule, as it does not require people to specify precise weights associated with each attribute. But both rules require people to examine all information for each alternative, determine the sums associated with each alternative, and compare those sums.

Non-Compensatory Decision Rules

Non-compensatory decision rules do not require decision makers to explicitly consider all salient attributes of an alternative, assign numeric weights to each attribute, or compute weighted sums in one’s head. Thus they are far less cognitively taxing than compensatory rules. The decision maker need only examine the attributes that define cutoffs in order to make a decision (to exclude options for a conjunctive rule, or to include them for a disjunctive one). The fewer attributes that are used to evaluate a choice alternative, the less taxing the rule will be.

Conjunctive rules require that an alternative must be acceptable on one or more salient attributes. For example, in the context of residential choice, a house that is unaffordable will never be chosen, no matter how attractive it is. Similarly, a man looking for romantic partners on an online dating website may only search for women who are within a 25-mile radius and do not have children. Potential partners who are unacceptable on either dimension are eliminated from consideration. So conjunctive screening rules identify “deal-breakers”; being acceptable on all dimensions is a necessary but not sufficient criterion for being chosen.

A disjunctive rule dictates that an alternative is considered if at least one of its attributes is acceptable to chooser i. For example, a sociology department hiring committee may always interview candidates with four or more American Journal of Sociology publications, regardless of their teaching record or quality of recommendations. Similarly (an especially evocative yet somewhat fanciful example), a disjunctive rule might occur for the stereotypical “gold-digger” or “gigolo,” who targets all potential mates with very high incomes regardless of their other qualities. Disjunctive heuristics are also known as “take-the-best” or “one good reason” heuristics that base their decision on a single overriding factor, ignoring all other attributes of decision outcomes ( Gigerenzer & Goldstein 1999 ; Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier 2011 ; Gigerenzer 2008 ).

While sociologists studying various forms of deliberative choice do not typically identify the decision rules used, a handful of empirical studies demonstrate that people do not consider all salient attributes of all potential choice alternatives. For example, Krysan and Bader (2009) find that white Chicago residents have pronounced neighborhood “blind spots” that essentially restrict their knowledge of the city to a small number of ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods. Daws and Brown (2002 Daws and Brown (2004) find that, when choosing a college, UK students’ awareness and choice sets differ systematically by socioeconomic status. Finally, in a recent study of online mate choice, Bruch and colleagues (2016) build on insights from marketing and decision research to develop a statistical model that allows for multistage decision processes with different (potentially noncompensatory) decision rules at each stage. They find that conjunctive screeners are common at the initial stage of online mate pursuit, and precise cutoffs differ by gender and other factors.

THE ROLE OF EMOTIONAL FACTORS IN DECISION PROCESSES

Early decision research emphasized the role of cognitive processes in decision-making (e.g., Newell & Simon 1972 ). But more recent work shows that emotions—not just strong emotions like anger and fear, but also “faint whispers of emotions” known as affect ( Slovic et al. 2004 , p. 312)—play an important role in decision-making. Decisions are cast with a certain valence, and this shapes the choice process on both conscious and unconscious levels. In other words, even seemingly deliberative decisions, like what school to attend or job to take, may be made not just through careful processing of information, but based on intuitive judgments of how a particular outcome feels ( Loewenstein & Lerner 2003 ; Lerner et al. 2015 ). This is true even in situations where there is numeric information about the likelihood of certain events ( Denes-Raj & Epstein 1994 ; Windschitl & Weber 1999 ; Slovic et al. 2000 ). This section focuses on two topics central to this area: first, that people dislike making emotional tradeoffs, and will go to great lengths to avoid them; and second, how emotional factors serve as direct inputs into decision processes. 7

Emotions Shape Strategies for Processing Information

In the previous section, we emphasized that compensatory decision rules that involve tradeoffs require a great deal of cognitive effort. But there are other reasons why people avoid making explicit tradeoffs on choice attributes. For one, some tradeoffs are more emotionally difficult than others, for example the decision whether to stay at home with one’s children or put them in day care. Some choices also involve attributes that are considered sacred or protected ( Baron & Spranca 1997 ). People prefer not to make these emotionally difficult tradeoffs, and that shapes decision strategy selection ( Hogarth 1991 ; Baron 1986 ; Baron & Spranca 1997 ). Experiments on these types of emotional decisions have shown that, when facing emotionally difficult decisions, decision-makers avoid compensatory evaluation and instead select the alternative that is most attractive on whatever dimension is difficult to trade off ( Luce et al. 2001 ; Luce et al. 1999 ). Thus, the emotional valence of specific options shapes decision strategies.

Emotions concerning the set of all choice alternatives—specifically, whether they are perceived as overall favorable or unfavorable—also affects strategy selection. Early work with rats suggests that decisions are relatively easy when choosing between two desirable options with no downsides ( Miller 1959 ). However, when deciding between options with both desirable and undesirable attributes, the choice becomes harder. When deciding between two undesirable options, the choice is hardest of all. Subsequent work reveals that this finding extends to human choice. For instance, people invoke different choice strategies when forced to choose “the lesser of two evils.” In their experiments on housing choice, Luce and colleagues (2000) found that when faced with a set of substandard options, people are far more likely to engage in “maximizing” behavior and select the alternative with the best value on whatever is perceived as the dominant substandard feature. In other words, having a suboptimal choice set reduces the likelihood of tradeoffs on multiple attributes. Extending this idea to a different sociological context, a woman confronted with a dating pool filled with what she perceives as arrogant men may focus her attention on selecting the least arrogant of the group.

Emotions as Information