Welcome to the new Ploughshares website!

For answers to frequently asked questions, please visit this page.

Literary Blueprints: The Wise Fool

After meeting Gothic characters the Byronic Hero and the Mad Woman , the time has come to visit periods before Romanticism in discovering a popular character known as The Wise Fool.

Origin Story: The idea of the Wise Fool is somewhat hard to trace. Unlike some other character types, he does not have a clear beginning, but rather a few key moments in literary history where he pops up in some form. Greek and Roman literature both contain examples of the Wise Fool, who often appears as a servant who tricks his master.

Looking at Biblical origins, the idea of the Fool is not someone who is lacking in intelligence, but someone who is a non-believer. The pairing of wisdom and folly perhaps originates in the book of Proverbs, in this case as a set of women, one with worth beyond all things (Wisdom) and one sent to lead men astray (Folly). These foils appear throughout Medieval literature in works such as Chaucer’s Tale of Melibee .

The idea of the Fool was more fully developed during the Middle Ages, although he wisdom will come with the Renaissance. The paradox of the Wise Fool, however, does not fully emerge until the Tudor period, most famously in Shakespeare’s King Lear where his Fool is the true source of wisdom in the play.

Characteristics: The Wise Fool is often literally a fool or jester—a comic character who is present for entertainment rather than intellect. Of course, the character has developed beyond those restrictions. Whatever his occupation, the Wise Fool is an outsider who is not valued for his (or her) intellect. It is there that the Fool is able to source his power. By being free from the standards of society, an outsider in essence, the Fool can observe and comment with few limitations, including mocking the social elite. But, like the cursed Greek prophet Cassandra, the truth of the Fool’s words may be missed by characters who dismiss them as worthless. His wisdom stems not from acquired knowledge but from common sense and insight. In modern literature, the Fool may suffer from some mental handicap which causes him to be perceived as unintelligent; however, he will have an innate gift that fuels his wisdom. The term Idiot Savant may be applied in this case. The Wise Fool can sometimes merge with the Trickster.

Famous Faces: Beginning with the Greeks, Philippus in Xenophon’s Symposium and Thersites in Homer’s Iliad both fill the role of the Wise fool. Shakespeare loved a Wise Fool, as evidenced by Twelfth Night’s Feste and the infamous Falstaff ( The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV ). Lear ’s Fool is so important to this Blueprint that Christopher Moore dedicated two books ( Fool and The Serpent of Venice ) to the character whom he names Pocket. John Steinbeck plays with the idea of the Idiot Savant with Of Mice and Men’s Lenny. Phillipa Gregory wrote a female Wise Fool in The Queen’s Fool . Harry Potter fans might recognize Luna Lovegood as a Wise Fool, though some argue Ron Weasley better defines the characteristics.

Similar Posts

Literary Enemies: Marilynne Robinson vs. Flannery O’Connor

Literary Enemies: Flannery O’Connor vs. Marilynne Robinson Disclaimer: Marilynne Robinson has no enemies. I hope you’ve never compared Marilynne Robinson to Flannery O’Connor, but I can see how you might have been tempted. There’s Iowa, first of all, and if it weren’t a proper noun I would have capitalized it anyway. Flannery O’Connor studied at…

In Praise of Unlikeable Characters

Doris Lessing’s Martha Quest begins, marvelously, with one of the best depictions of adolescent malaise I’ve ever read: the fifteen-year-old title character languishing on her porch in silent, miserable judgment (in “spasms of resentment”) while her mother knits, and gossips vacuously with a neighbor.

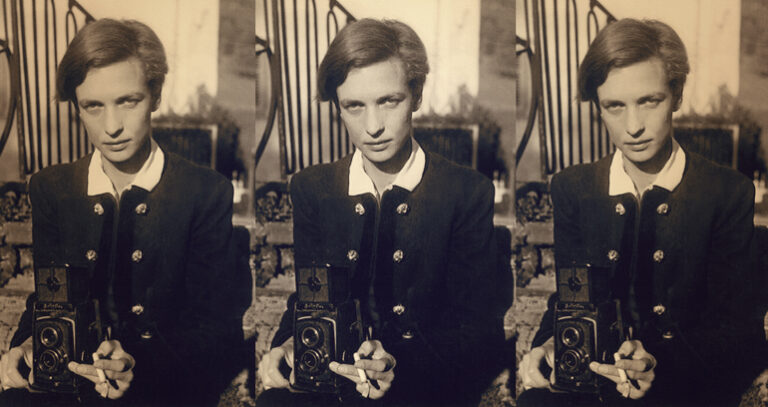

“She had a face that would haunt me for the rest of my life”: Looking for Annemarie Schwarzenbach

Grappling with the complexities of Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s life–falling in love with her, in a way–entails addressing not just her political and ideological stances in light of her personal relationships, but also the realities of queerness within history, and the interplay of both of these aspects.

Review Cart

No products in the cart.

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

The Praise of Folly

Desiderius erasmus.

One of the core arguments of The Praise of Folly is the idea that humanity’s conventional understanding of foolishness and wisdom is flipped. Written from the perspective of Foll y, the essay aims defend to folly from those who might condemn it, suggesting that fools often act more wisely than the wise, and that the wise often behave more foolishly than fools. For instance, Folly asks her readers to consider the things that scholars sacrifice to become truly educated: they shut themselves up in their studies, isolating themselves from the world and the people around them. Their wisdom, in other words, comes at the expense of health, looks, livelihood, sociality, and ultimately, happiness. Moreover, Folly argues that the life of a scholar does not even lead to true wisdom, for the person who shuts themselves away deprives themselves of the opportunity to truly experience the world. A person who is unwilling to go out and take risks—or rather, act foolishly—will never acquire the wisdom of someone who has made mistakes and learned from them. In this way, Folly shows that wisdom can, ironically, look quite foolish.

Of course, much of this argument depends on how one defines wisdom. For her part, Folly loosely defines wisdom as the successful pursuit of happiness, a plausible, if albeit convenient, definition. While it allows her to easily portray any painful sacrifice for knowledge as “foolish,” the definition disregards other more traditional components of wisdom, like the accumulation of information and knowledge. As such, Folly’s argument is more a reinterpretation of wisdom than a genuine attempt to throw away conventional understands of wisdom. The point of Folly’s argument, then, is not that folly and wisdom are incorrectly defined and should be swapped, but rather that binaries like these, when inspected from new angles, often reveal themselves to be more fluid than society might define them.

Folly vs. Wisdom ThemeTracker

Folly vs. Wisdom Quotes in The Praise of Folly

Nothing is more puerile, certainly, than to treat serious matters triflingly; but nothing is more graceful than to handle light subjects in such a way that you seem to have been anything but trifling. The judgement of others upon me will be what it will be. Yet unless self-love deceives me badly, I have praised folly in a way that is not wholly foolish.

However mortal folk may commonly speak of me (for I am not ignorant how ill the name of Folly sounds, even to the greatest fools), I am she – the only she, I may say–whose divine influence makes gods and men rejoice.

So it is from this brisk and silly little game of mine come forth the haughty philosophers (to whose places those are vulgarly called monks have now succeeded), and kings in their scarlet, pious priests, and triply most holy popes; also, finally, that assembly of the gods of the poets, so numerous that Olympus, spacious as it is, can hardly accommodate the crowd.

Old age would not be tolerable to any mortal at all, were it not that I, out of pity for its troubles, stand once more at its right hand; and just as gods of the poets customarily save, by some metamorphoses or other, those who are dying, in like manner I bring those who have one foot in the grave back to their infancy again, for as long as possible; so that the folk are not far off in speaking of them as “in their second childhood.”

For do you not see that the austere fellows who are buried in the study of philosophy, or condemned to difficult and wracking business, grow old even before they have been young–and this because by cares and continual hard driving of their brains they insensibly exhaust their spirits and dry up their radical moisture. On the contrary, my morons are as plump and sleek as the hogs of Acarnania (as the saying is), with complexions well cared for, never feeling the touch of old age; unless as rarely happens, they catch something by contagion from the wise—so true it is that the life of man is not destined to be happy.

In sum, no society, no union in life, could be either pleasant or lasting without me. A people does not for long tolerate its prince, or a master tolerate his servant, a handmaiden her mistress, a teacher his student, a friend his friend, a wife her husband, a landlord his tenant, a partner his partner, or a boarder his fellow-boarder, except as they mutually or by turns are mistaken, on occasion flatter, on occasion wisely wink, and otherwise soothe themselves with the sweetness of folly.

As nothing is more foolish than wisdom out of place, so nothing is more imprudent than unseasonable prudence.

Although that double-strength Stoic, Seneca, stoutly denies this, subtracting from the wise man any and every emotion, yet in doing so he leaves him no man at all but rather a new kind of god, or demiurgos, who never existed and will never emerge. Nay to speak more plainly, he creates a marble simulacrum of a man, a senseless block, completely alien to every human feeling.

Consider, among the several kinds of living creatures, do you not observe that the ones which live most happily are those which are farthest from any discipline, and which are controlled by no other master than nature? What could be more happy than the bees—or more wonderful?

And yet a remarkable thing happens in the experience of my fools: from them not only true things, but even sharp reproaches, will be listened to; so that a statement which, if it came from a wise man’s mouth, might be a capital offense, coming from a fool gives rise to incredible delight.

Hence there is either no difference, or if there is a difference, the state of fools is to be preferred. First their happiness costs least. It costs only a little bit of illusion. And second, they enjoy it in the company of so many others. The possession of no good thing is welcome without a companion.

And yet through a cloud, or as in a dream, they know one thing, that they were happiest while they were out of their wits. So they are sorry to come to themselves again and would prefer, of all good things, nothing but to be mad always with this madness. And this is a tiny little taste of that future happiness.

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays.

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

Wit, and't be thy will, put me into good fooling! Those wits that think they have thee do very oft prove fools; and I that am sure I lack thee may pass for a wise man. For what says Quinapalus? 'Better a witty fool than a foolish wit.'

Shakespeare's plays were written to be performed to an audience from different social classes and of varying levels of intellect. Thus they contain down-to-earth characters who appeal to the working classes, side-by-side with complexities of plot which would satisfy the appetites of the aristocrats among the audience. His contemporary status is different, and Shakespeare's plays have become a symbol of culture and education, being widely used as a subject for academic study and literary criticism. A close critical analysis of Twelfth Night can reveal how Shakespeare manipulates the form, structure, and language to contribute to the meaning of his plays.

Through the form of dialogue Shakespeare conveys the relationship between characters. For example, the friendship and understanding between Olivia, and her servant Feste, the clown, is shown in their dialogue in Act 1, Scene 5. In this scene Shakespeare shows that both characters are intellectuals by constructing their colloquy in prose.

Characterising Feste, Shakespeare gives him the aphorism,

This line illustrates the clown's acumen; and is a delightful example of the way in which he uses language, as well as form to manifest Feste's character. Far from being a fool, the clown is erudite and sagely and able to present the audience with a higher knowledge of the plot than that presented by the other characters in the play. This witty remark is a clear indication of his aloofness from the events of the play. He can look upon the unfolding scenario with the detachment of an outsider due to his minimal involvement with the action. Feste is a roaming entertainer who has the advantage of not having to take sides; he is an observer not a participant.

Another illustration of the way in which Shakespeare uses form to give meaning is in the dialogue between Viola and the Duke Orsino in Act 2 scene 4, where one line of iambic pentameter is frequently shared by the two characters. For example:

The merging of the characters' half-lines into one whole line is cleverly used by Shakespeare to show that the two characters are destined to be together. This technique of linking lines, which Shakespeare uses elsewhere, for example in Romeo and Juliet , shows the balance that the two characters provide for each other. This is an example of how he uses the form of language to aid the actors in portraying the characters in the way he intends.

The structure of a Shakespeare play also contributes to its meaning. In most of his plays there is a pattern consisting of three main sections:

Exposition - establishing the main character relationships in a situation involving a conflict.

Development - building up the dramatic tension and moving the conflict established to its climax. (In Twelfth Night , increasing complications resulting from love, and mistaken identity.)

Denouement - resolution of the conflict and re-establishing some form of equilibrium. (In Twelfth Night , the realisation of the disguises and the pairing up of the characters.)

The scenes of Twelfth Night are carefully woven together in order to create tension and humour, and to prepare us, almost subconsciously, for what is going to happen. We are given fragments of manageable information throughout the play so that when the complex plot unfolds we understand it by piecing together all the information given to us in previous scenes. For example, to return to the Duke and Viola, the audience is aware of the fact that she is disguised as a man, so understands more than the Duke himself does as he struggles with his feelings, believing he is falling in love with a man.

The audience is fed important information in Act 2 Scene 1 when Antonio and Sebastian meet and converse:

Through these lines Shakespeare lets the audience in on the fact that Sebastian is alive, and that he believes his sister Viola to be dead, and that the two resemble one another in appearance. We also see how Sebastian feels for his sister as he talks about her so passionately. This is an important part of the development stage of the play as it prepares us for the role which mistaken identity will play in the plot, and sets up the potential for dramatic irony.

Another scene which prepares us for dramatic irony is when Maria, Sir Andrew, and Sir Toby write the letter to Malvolio, under the pretence that it is from Olivia. As we the audience are aware of this deception it sets up the dramatic irony, because Malvolio himself is not aware of it when he finds and reads the letter during Act 2, Scene 5. Presuming the letter is for him, and from Olivia, he proceeds to embarrass himself.

The structure in which many subplots run through the play can be described as 'River Action'; actions not closely linked are moving in parallel to be integrated at the end of the play. This contrasts to the single or episodic action in Macbeth , or the mirror action in King Lear where there is both a main and a sub-plot present. Shakespeare has used this structural technique to create both humour and tension. The subplots also pick up on the themes of love and mistaken identities, preparing us for the part those themes will play in the main plot.

Shakespeare also supports the events and actions in the play through language, using it to convey to the audience the feelings and thoughts of the characters as they respond to events.

Language is used first and foremost for the purpose of conveying a difference in feelings or attitudes in different situations. For example Malvolio speaks in prose at the beginning of the play, showing intelligence, but near the end he speaks in verse;

Here Shakespeare has distorted the rhythm so that it cannot fit the rule of iambic pentameter, thus showing that Malvolio is feeling strong emotion. His confusion and humiliation becomes apparent through the breathless manner in which he speaks.

In contrast, we have these smoothly-flowing lines from Orsino:

By using iambic pentameter here Shakespeare defines Orsino's character to a certain degree. Iambic pentameter shows control and yet the emphasis here is on the instability and the intensity of his love for Olivia. The audience cannot help but feel pity towards his self-induced love sickness, but at the same time the situation provokes hilarity, as he has never actually met Olivia. This leads us to believe he is 'in love with being in love'.

Characters are there to instigate an emotional reaction from the audience, and when considering the characters of a Shakespeare play we may find as much characterisation as in a novel, but we must also consider that the characters have a mechanical function in the scheme of the play as a whole. It can help to think of them as vehicles to carry ideas or themes; for example Orsino introduces the theme of love.

The diction Shakespeare gives to his characters contributes to their characterisation. He gives characters with more intelligence a large vocabulary, where feeble-minded characters are more limited. Evidence of this in Twelfth Night is perhaps not as obvious as in other plays such as The Tempest , where Caliban has a very limited vocabulary, and struggles to find words. But characteristics of language such as imagery, metaphors, vocabulary and syntax used by Malvolio contrast for example with those used by the Clown. Although both characters are of a higher intelligence, the language chosen for each is very different;

Feste, the Clown, often plays with words, uses puns and aphorisms.

He proves to be intelligent in that he is witty and wise. He also proves to be quite mysterious, seeming to know more than most, but still being observant and quiet.

Malvolio is more well-spoken than witty, but he is more pompous and arrogant.

That final line from Malvolio's is there to make the audience pity him. By using the metaphor of 'the whole pack of you' an image is immediately created of a group surrounding him. The metaphor describes how he has been made a fool of by all of them, and also signifies his isolation from the rest of the cast and how he has become a loose end of the play, as everybody else has found love or companionship with another person in the play.

After analysing the way in which Shakespeare uses form, structure and language to shape meaning I have come to the conclusion that we are not consciously aware of these techniques when we are the audience. Directors and actors may take these factors into consideration when performing a play, to assist in conveying meaning to the audience. Different directors may interpret the text in different ways, but the play should be performed in such a way that subtle clues help the audience receive messages and understand the complexity of the developing plot, so that we are not obliged to be continually struggling to interpret the text for ourselves.

- Aristotle: Poetics

- Matthew Arnold

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Henry Fielding

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

- Ernest Hemingway

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Carl Gustav Jung

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Tom Stoppard

- William Wordsworth

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Studying English Literature

- The author, the text, and the reader

- What is literary writing?

- Indian women's writing

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Renaissance poetry

- The Age of Reason

- Romanticism

- New York! New York!

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

- The Spy in the Computer

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

evoke laughter with his ignorance- and the wise fool, in whom wit and piercing satire supplement low comedy. Shakespeare’s body of work developed a complex variety of interpretations for the fool, a character trope that Elizabethan audiences would have been able to sum up at a glance.

Literary Blueprints: The Wise Fool. Reading | Series. By Amber Kelly March 26, 2015. After meeting Gothic characters the Byronic Hero and the Mad Woman, the time has come to visit periods before Romanticism in discovering a popular character known as The Wise Fool.

The wise fool, or the wisdom of the fool, is a form of literary paradox in which, through a narrative, a character recognized as a fool comes to be seen as a bearer of wisdom. [2]

Rather than tempt a sweeping survey of the entire Dickensian canon, I have chosen three representative figures - Dick Swiveller, Barnaby Rudge, and Pinch - to illuminate the moral, symbolic, and psychological nature. Dickens' wise fools. "Wise fool" is a generic term embracing several distinct character types.

Fool: Why to keep one's eyes of either side's nose, that what a man cannot smell out, he may spy into. Lear: I did her wrong. Fool: Canst tell how an oyster makes his shell? Lear: No.

Written from the perspective of Foll y, the essay aims defend to folly from those who might condemn it, suggesting that fools often act more wisely than the wise, and that the wise often behave more foolishly than fools.

Shakespeare introduces the figure of the Fool, as the central character in all his comedies, and probably the principal spokesman of his own view of life. The particular advantage, and so the outstanding quality, of the Fool is that he is free to say what he likes without fear of the contempt of others or the punishment of his superiors.

Shakespeare: Twelfth Night. Wit, and't be thy will, put me into good fooling! Those wits that think they have thee do very oft prove fools; and I that am sure I lack thee may pass for a wise man. For what says Quinapalus? 'Better a witty fool than a foolish wit.'

In calling Falstaff a compound of sense and vice, Johnson points directly at the oxymoronic nature of the wise fool.

Free Essay: The Wise Fools of Shakespeare “Infirmity that decays the wise doth ever make a better fool” – though uttered by one of his own characters...