Shopping Cart

No products in the cart.

Aphantasia – A Blind Mind’s Eye

- February 24, 2023

Share This Post

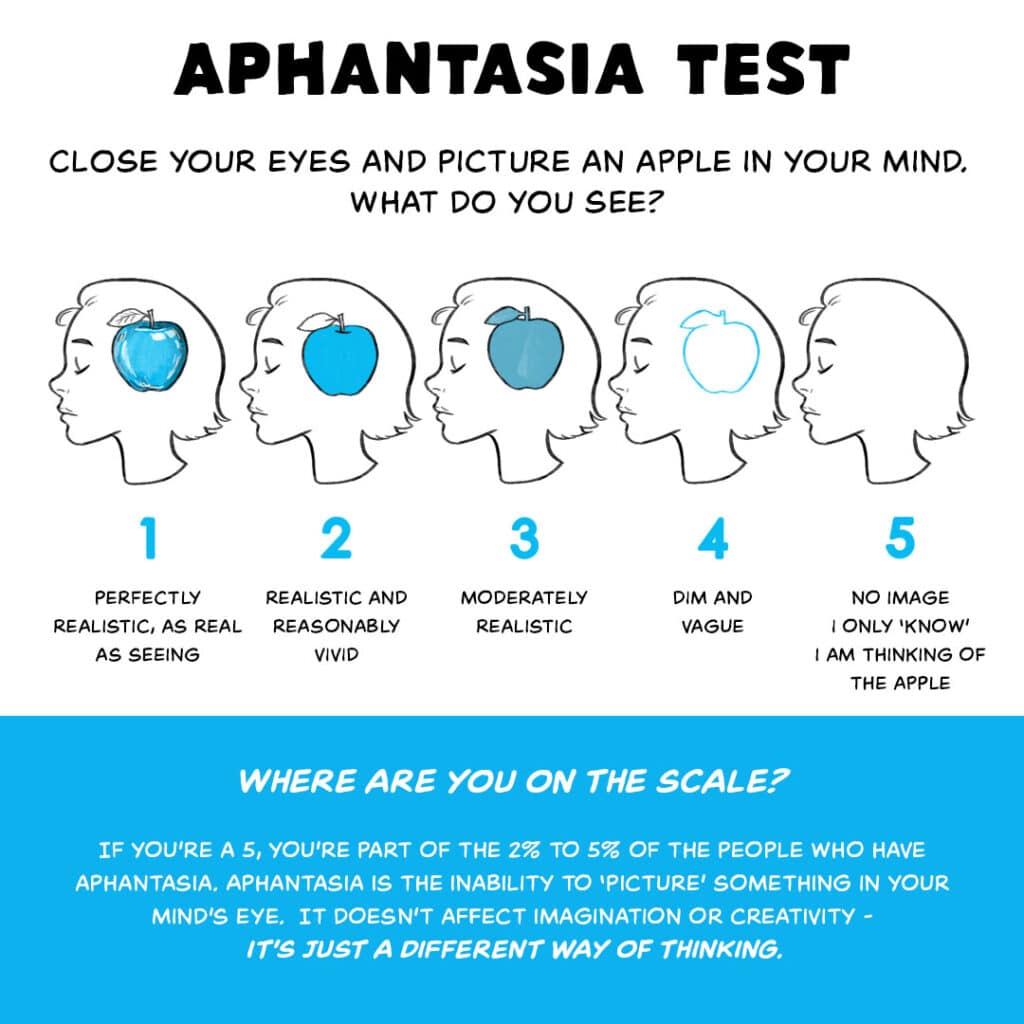

This week the brilliant minds at We Are Cognitive (the studio who animated SKR’s RSA Animate and A Future for Us All ) created and shared their version of a common simple aphantasia test above. It asks you to close your eyes and imagine an apple, then judge the clarity of the apple based on the scale of 1 – 5. If you score a 5, if you cannot see any apple at all but know you are thinking of an apple, then you might have a condition called aphantasia.

The Aphantasia Network defines the condition as “the inability to visualize. Otherwise known as image-free thinking .” They go on to say that “people with aphantasia don’t create any pictures of familiar objects, people, or places in their mind’s eye. Not for thoughts, memories, or images of the future.”

This means that people with aphantasia lack the ability to be visually imaginal – to bring to mind image s of things they have previously experienced – and visually imaginative – to bring to mind images of things they have never experienced.

The important word to note here is “visually.” Aphantasia does not mean a complete lack of imagination, it means a lack of visual imagination.

What we know about imagination is that it exists on a spectrum. Like the rest of human intelligence, our capacity to imagine is unique to each of us. The organisation Imagination Spectrum identifies at least six different capacities of imagination, and we all have a unique blend of each. They are:

Visual Imagination – The ability to imagine pictures in your mind without actually seeing them with your eyes.

Auditory Imagination – The ability to imagine sound in your mind without actually hearing with your ears.

Olfactory Imagination – The ability to imagine smells in your mind without actually smelling with your nose.

Gustatory Imagination – The ability to imagine tastes in your mind without actually tasting with your tongue.

Tactile Imagination – The ability to imagine sensations in your mind without actually feeling with your body.

Motor Imagination – The ability to imagine movements in your mind without actually moving with your body.

People with aphantasia lack or have decreased capacity for the first, Visual Imagination, but not necessarily the other five. It is currently estimated that 2-5% of the population have aphantasia, and that about 26% of these people have “total aphantasia” or aphantasia that is multisensory, that affects all of their sensory imaginations.

Even for the very small percentage of the population that has total aphantasia, the condition does not mean they do not have imaginations. Imagination is a nuanced and complicated phenomenon. It allows us to bring to mind things that aren’t immediately present to our senses, and even without being able to do this in a sensory capacity the ability to imagine is still very much present.

The Aphantasia Network writes that “while this may seem puzzling at first glance, on reflection, imagination is a much richer and more complex capacity than the ability to visualize. Visualization enables most of us to picture things to some degree in our mind’s eye: imagination allows us to represent, reshape and reconceive things in their absence. Aphantasia illustrates the wide variety of types of ‘representation’ available to human minds and brains.”

Over the past several months I have spoken to a number of people with aphantasia, and almost all of them have said they were baffled to learn that other people can actually bring images to mind. They assumed that when people say “picture an apple” they mean it more metaphorically than literally. It goes to show just how universal we assume our experiences are, and brings back the mind scrambling question of “how do I know if my red is the same as your red?”

It’s worth noting that the people I have spoken to have self-diagnosed as having aphantasia. This is for several reasons: as aphantasia is an understudied area of neuroscience that has very little awareness surrounding it, formal testing is very rare. Also, our relationship with our imaginations is highly personal and subjective. No one knows your imagination except you, so who better to make a diagnosis. That said, if only 2-5% of the population have aphantasia, then either I know a disproportionate amount of people with the condition, or that percentage is far too low, or the “picture an apple” test is an oversimplification.

When I close my eyes I cannot picture an apple. When I close my eyes I see the inside of my eyelids. However, when I open my eyes and imagine an apple, I can bring one clearly to mind. I have very vivid daydreams, and yet struggle in any guided meditation to visualise the imagery prompts. If I was judging myself on the “picture an apple” test alone, I would absolutely diagnose myself with aphantasia, but I know that I don’t have it because in other circumstances I can bring clear images to mind. I also know that I panic in routine eye exams in case I give the wrong answer. When promoted to close my eyes and think of an apple I can’t make one appear on demand, but in the middle of the night when I can’t fall back to sleep, I can visualise all sorts of things (many I wish I hadn’t). The point is, our capacity to imagine is more nuanced than even our basic ability to imagine – circumstance, situation, interest, all play a role, in amongst other factors.

The Aphantasia Network suggests a more in-depth test called the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire to help diagnose aphantasia. This test is an extended version of the apple test, and is currently the next best step if you think you might have the condition. (It was created in 1975 and last updated in the 1990s, and so I do wonder if the huge advancements in neuroscience since the 1990s might make a more recent update to the test worthwhile).

Very interestingly, new research into aphantasia was released last year. A team of researchers from the University of New South Wales, Australia, studied the pupil dilation of their subjects. They found that when subjects were asked to visualize “dark” or “bright” mental images, the size of their pupils dilated. In fact, the study found that the vividness of someone’s mental imagery correlates with changes in pupil size or lack thereof. Those subjects with strong capacities for mental visualisation had larger pupils during the visualisation process than those without.

The study also looked at people with aphantasia and found that while subjects had normal pupil dilation when looking at bright or dark objects, their pupils stayed the same size during the mental visualisation exercises.

Aphantasia and Creativity

A common concern in the people with aphantasia that I have spoken to is whether or not the condition affects their ability to be creative. The answer is a resounding no. Having aphantasia does not show any correlation with decreased creative capacity. In fact, some highly successful, highly creative individuals have famously had aphantasia: Ed Catmull , co-founder of Pixar and former president of Walt Disney Animation Studios. Craig Venter , the biologist who first sequenced the Human Genome. Blake Ross , creator of Mozilla Firefox. Glen Keane , Disney Animator and Creator of The Little Mermaid. Penn Jillette of Penn and Teller.

Creativity is the process of having original ideas that have value. As we have discussed often on TCR, imagination is a key aspect in the creative process. Creativity is “applied imagination.” Not only have we established that aphantasia does not mean a lack of imagination, we also know that the creativity often thrives when presented with boundaries or obstacles to overcome. The human mind is inherently creative and adaptive.

What is so amazing about the human brain is just how much we still have to learn about it. As more awareness is brought to aphantasia, I am excited to learn even more about the spectrum of imagination. It goes to show once again just how important it is to connect with our own unique capacities of imagination and creativity, and to encourage each generation to do the same: we all bring something new to the table.

For more information and support surrounding aphantasia, check out the Aphantasia Networ k.

We will soon be speaking to Dr Amir Amedi for the Creative Revolution Podcast. Dr Amedi is a neuroscientist who has studied the neuroscience of imagination. If you have any questions you would like us to ask him about aphantasia, or any other aspect of imagination and neuroscience, please let us know below!

Sign in , or join the Revolution , to view the comments.

Ignite your creative journey, embark on a journey of self-discovery, creative freedom, and professional growth. join our global community of creative thinkers, innovators, and pioneers. the creative revolution is more than a membership – it's a movement., more to explore.

New Feature: TCR WhatsApp Group

We’re excited to introduce a new way to stay connected on the go: The TCR WhatsApp Group.

Naming My Imaginary Friend: An ADHD Journey

Living with undiagnosed ADHD: A personal reflection on receiving an adult diagnosis. This post explores the realities of ADHD beyond attention deficit, including its emotional impact and lesser-known symptoms. It delves into the challenges of fitting a neurodiverse brain into a neurotypical world, while also recognizing the unique strengths that come with neurodiversity. In it I contemplate how we can better support and champion neurodiverse individuals, especially in educational settings.

Reclaim Your Creativity. Starting Now

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

- Message this member

- Add this member as a connection

Please note: This action will also remove this member from your connections and send a report to the site admin. Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

special offer!

Looking to unlock the full course.

We’re so pleased to find that you’ve enjoyed the mini-course so much you wish to unlock more!

As a special thank you, we’d like to give you one month free access to Pro Membership at The Creative Revolution. Continue learning with unlimited access to all our courses, articles, projects, groups, events and more for free – and then just $36/month after.

We look forward to welcoming you to the community.

FINAL OFFER!

Try The Creative Revolution For a 30-Day free Trial Today (… and get access to the digital bonuses for free!)

“Wow, they really want me to join The Creative Revolution!”

You bet we do! We genuinely believe that The Creative Revolution holds the transformative power for anyone, irrespective of their background or expertise, to awaken their creativity, elevate their potential and create a future for us all!

(Trust us, once you plunge into the depths of the Education Values Challenge… you’ll immediately recognise the exponential value of being a part of The Creative Revolution community.)

Usually, our policy is rock-solid: no free trials for The Creative Revolution. But just for you, right here, right now, we’re making an exception. Why? Because we’re confident about the immense value and transformative experience our community provides.

You can now secure a full 30-day free trial of The Creative Revolution! Dive deep into creativity, learn from the best, and take tangible actions to manifest your dreams.

But remember — this is your final call to leverage this unique opportunity. This offer disappears when you leave this page…

So, don’t wait!

Click the “Join The Revolution” button below before this offer is gone for good…

No thanks, I'm not interested... please take me to the confirmation page

Register for 'the educational values workshop' for free today.

Put in your primary email address below to claim your place before it fills up!

Wow, they really want me to join The Creative Revolution!”

(Trust us, once you plunge into the depths of the Element 7-Day Challenge… you’ll immediately recognise the exponential value of being a part of The Creative Revolution community.)

You can now secure a FULL 30-day free trial of The Creative Revolution! Dive deep into creativity, learn from the best, and take tangible actions to manifest your dreams.

But remember — this is your FINAL CALL to leverage this unique opportunity. This offer disappears when you leave this page…

Register For The Workshop For FREE Today!

You’re in the archive, new junkee.Com (and stories) here.

- The Junkee Takeaway

- About Junkee

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Turns Out Not Everyone Can Picture Things In Their Mind And Sorry, What?

Oh no, I just got over the whole "not everyone has an inner-monologue" thing.

The Neurocritic

Deconstructing the most sensationalistic recent findings in Human Brain Imaging, Cognitive Neuroscience, and Psychopharmacology

Wednesday, May 04, 2016

Imagine these experiments in aphantasia.

Aphantasia: How It Feels To Be Blind In Your Mind I just learned something about you and it is blowing my goddamned mind. . . . Here it is: You can visualize things in your mind. If I tell you to imagine a beach, you can picture the golden sand and turquoise waves. If I ask for a red triangle, your mind gets to drawing. And mom’s face? Of course. . . . I don’t. I have never visualized anything in my entire life. I can’t “see” my father’s face or a bouncing blue ball, my childhood bedroom or the run I went on ten minutes ago. I thought “counting sheep” was a metaphor. I’m 30 years old and I never knew a human could do any of this. And it is blowing my goddamned mind.

To my astonishment, I found that the great majority of the men of science to whom I first applied, protested that mental imagery was unknown to them, and they looked on me as fanciful and fantastic in supposing that the words 'mental imagery' really expressed what I believed everybody supposed them to mean. They had no more notion of its true nature than a colour-blind man who has not discerned his defect has of the nature of colour. They had a mental deficiency of which they were unaware, and naturally enough supposed that those who were normally endowed, were romancing.

Quick poll (please RT!): Can you draw up an image in your mind's eye...? — Kevin Mitchell (@WiringTheBrain) May 3, 2016

Mental images poll. Is 'mental image' a misnomer? Pls RT, this stuff is weird. (CC: @WiringTheBrain ; @blakeross ). — Ed Berry (@ed_berry) May 3, 2016

My own conclusion is, that an over-readiness to perceive clear mental pictures is antagonistic to the acquirement of habits of highly generalised and abstract thought, and that if the faculty of producing them was ever possessed by men who think hard, it is very apt to be lost by disuse. The highest minds are probably those in which it is not lost, but subordinated, and is ready for use on suitable occasions.

Subscribe to Post Comments [ Atom ]

26 Comments:

I didn't understand this until recently either. But I come from a family with a hilarious history of what we always called the "sense of direction" gene. Half of us lack any grasp of direction, which now makes me wonder if it's a mental mapping visualization problem. We were joking about our GPS savior on twitter as well. But one of the things that I remember in my youth was taking that ASVAB test that the army would do. I took it in high school. There was one section of the test that I didn't even understand. You had to look at these blocks and you had to rotate them in your mind somehow and predict what the other side would show (or something). I got 90th percentiles on every other section of this test, and that block-rotations section was no better than chance. I've been baffled by that for 40 years now. But I think this may be why. I wonder if you could look through old ASVAB data at this?

Mary - Thanks for your comment, that's a very good idea. According to the official site , "The ASVAB was introduced in 1968. Over 40 million examinees have taken the ASVAB since then." Wow! That's a huge database. But first, you'd have to find out how willing they'd be to share the data, and see if there are any questions that assess visual imagery.

So do aphantasiac people have visual dreams?

That's a great question. It seems to be split: some do, others don't. Check out these comments on a 2010 post by @PsychScientists. Here's a new comment from May 4 : "I can remember a lot of details about something I have seen or heard..I have a great memory for faces and objects that I have only seen once or just a few times. You can't gross me out nor do I have a problem going to sleep after watching a gory movie because I get no images." This individual seems to be unusual; many others have poor memories. In Zeman et al. (2015), 17/21 reported involuntary imagery during dreams. There is so much interesting research that can be done!

Oh, I forgot this part of the 4 May 2016 comment: "... I see no images at all. But, I have very vivid dreams and have a great memory (better than most people)."

Imagine you were living at a time before language had been invented. Surely these early Humans only had the mental images to enable them to draw cave paintings for example. I also believe this ability and our visual memory became compromised when we developed language and this enables those without the ability to see mental pictures to survive through language development. Perhaps those with creative talents had ability through genes responsible for schizophrenia hence its survival and those without mental visualisation had none.

Excellent article and a great introduction - its good to be reminded that this mental blindness has been known for many years yet has not penetrated the general consciousness. Most people have heard of colour blindness but only a few know of mental blindness. I am mentally blind - have been as long as I can remember - but that does not mean I do not have a visual memory - or that words with clear images (like elephant) are not easier to remember than words that are not (like whatever that other word was) - oddly with non visual images I can easily remember the first letter (C) even though I have no idea what the full word was. Before proposing a test you might want to run it by a wide sample of people with zero mental imaging because we have discovered that our memories are not all alike so assumptions like pictures do not make memory easier for those without mental imaging may be very wrong. I can do the memory game where you remember object by linking them (car on elephant in pool) but am limited to the number of items because my brain does not have a complete image but instead builds it step by step and the better they link to a story the easier it is to remember - elephant drove car into pool. I hope there is a lot more research done in the area and would love to see if their is a correlation between test scores and imaging ability. I believe this statement is not true for me: ", because the concreteness advantage (using imagery during encoding) could not be mobilized as an explicit (or perhaps implicit) strategy" I do imagine images (my apple is a gala) I just don't see them! What matters most to me is that we raise the awareness of the wide range of types of memories and help people understand that their really is no normal - simply a spectrum with photographic memory on one extreme and mental blindness on the other. We need parents and teachers to understand that not everyone learns the same way and penalizing a student because they can't recall a chart or a picture is unfair.

I used to have the ability to imagine pictures vividly. I remember designing objects as a child as a past time activity. Then with 16 I smoked a joint and had a bad trip, on which a several-year long depersonalisation disorder (DP) followed. From this point on I was unable to imagine anything visually, even after overcoming the disorder. According to DP forum members it is a common symptom of DP. I have great haptic imagination and normal acoustic, but visually it's almost gone.

website http://aphant.asia/index.php/forum Yes to dream imagery, and have lots of trouble with craters in astro-photography...

That's a very interesting topic. I'd find it also interesting to know if people with aphantasia can have visual halluzinations (or if someone with aphantasia could never have it). "I have great haptic imagination and normal acoustic" I can imagine things visually but I've always wondered (since I first read about it) what haptic imagination (or kinestetic imagination) is and I don't think I've acoustic imagination either. But then, I sometimes "hear" my alarm-clock ringing when it's not actually ringing, so I must know what it sounds like and I must have some kind of acoustic imagination?

Thanks for your additional comments. Sharon - I agree that raising awareness is important. Given the variation between individuals, as measured on the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), I imagine (i.e. suspect) this would influence the results. In my view, whether there are concreteness/imageability effects for words is an open question, which is why it would be interesting to study in those with aphantasia. When you say that you "imagine images (my apple is a gala) I just don't see them!" -- do you mean "imagine" as an abstract concept? Or do you imagine other sensory aspects (taste/smell/sound when biting into one)? drkrvn - I'm sorry about your DP (which is a distinctive feature, I believe). You raise the interesting point that your issue is with visual imagination only (and that it was acquired after drug use). It seems there's a lot of variation in the affected sensory modalities in those with congenital/developmental aphantasia. For some it's all senses, for others it's not. Non Significance - Do you ever "hear" songs and music in your mind's ear? Or get them stuck in your head, the "earworm" phenomenon. For me, musical imagery is more vivid than my visual imagery, which is pretty good but not crystal clear (i.e., not exactly like seeing in real life). Your point about visual hallucinations is fascinating, and raises the question about whether hallucinogenic drugs could induce visual percepts in those lacking visual imagery. Maybe not? I'M NOT ENDORSING SELF-EXPERIMENTATION, but for the population of aphantasics in the UK who have already experimented with LSD, mushrooms etc., then maybe a collaboration between Dr. Zeman and Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris (of LSD neuroimaging fame) would be most informative! Anonymous - thank for mentioning that site, you've given me the opportunity to expand on the links in the last paragraph of my post. Can’t form a mental image? No big deal. - Notes from Two Scientific Psychologists Aphantasia Community Aphantasia/Non-imager Group ...both of the above Facebook pages associated with the mega-community, Aphantasia Aphantasia Genetics Working group The Eye's Mind , University of Exeter

Great post. I have very strong auditory / music imagery. If I imagine a tune then I can actually hear it - I know it's not real but I hear it, not in a metaphorical sense. With visual imagery it's harder to describe. If I think of an apple I don't see an apple, at best I get certain vague visual percepts that are kind of like flashes of apple-like features. But these are only "imagery" in a metaphorical sense. I get visual imagery, often very vivid, in dreams. And I have experienced waking visual imagery under certain conditions (when I first started on the antidepressant mirtazapine, specifically, also on some other drugs). So in some sense my brain must be set up to produce these imagery, it just chooses not to most of the time...

Re: "some with aphantasia report severe deficits in autobiographical memory." It would also be good to add to your references the website for Brian levine's lab at Baycrest and their work on Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory (SDAM). http://sdamstudy.weebly.com/

Thank you, I've added a link to that site.

Thank you for your response. No, I’ve never had an earworm and I can’t hear songs in my mind (at all). (Yet, somehow, I do recognize songs which I’ve heard often enough… though I don’t know what they sound like before I hear them.) But then, some people with no visual imagery say that they have a good memory and can recognize people without having the ability to imagine them… That’s something I “can’t” do/find very hard, even though I have some (relatively vague, but still) visual imagery. Like Neuroskeptic I’ve also really vivid dreams, definitely a lot more “real” than visual imagery. (The next day(s) it sometimes feels like a (vivid) memory rather than a dream... So now I just need to manage to dream being on vacation and can train my brain while sleeping ;) )). I’ve also had medication induced visual hallucinations twice. Which were (maybe obviously) so real, that I couldn’t distinguish them from reality (at the time). But I’ve never had any increased waking visual imagery. I wonder how you (people who have very clear mental imagery, whether it’s visual, auditory or kinetic) can distinguish that from reality? Is it, that the mental imagery is willingly produced? (But then some people say, it’s not for them, they see what they think.) P.S.: I hope I didn’t post twice. There was an error before, so I tried again.

Like Sharon, I have never had any mental visual imagery and also feel like some of these suggestions of what would be impacted by a lack of mental imagery do not feel like they are necessarily true to my experience. Sometimes I wonder if I do have a visual image in my memory of certain things, I just can't actually "see" it in my mind, I just "know" the image. This seems to be a very difficult experience for those with mental imagery to understand, but in the Facebook group discussions, several people describe something very similar. If I were to "imagine an apple," my first thoughts right now are about it being crunchy to bite into and the size and weight of a generic apple. But if you were to ask about something that is more about the visual experience, sometimes it is like I almost see a picture, in that I know exactly the scene (I am thinking of a specific bridge in a park right now), but I can't actually "see" anything at all, yet I have a pretty immediate sense of knowing what it is and the colors that would be involved and where things are in the scene. Even though I see nothing, it feels more like looking at a picture than a verbal description. For some other things (especially faces) I have no such experience of an "invisible picture" and I can not recall what someone looks like unless I had a discussion or reason to remember a particular feature. I do remember what they look like in a way that I recognize them when I see them again. I also am able to do the test of imagining rotating an object in my mind. It takes some effort, but I "sketch out" and rotate the object in my mind to figure out the other perspective - I just don't see the object I am rotating. I do have a strong spatial/kinesthetic/proprioceptive awareness, so it feels to me as some combination of imagining the rotation as proprioceptive movement (which is a sense I definitely imagine), and very carefully visually tracking the invisible image I created in my mind. I know this sounds like a contradiction, but it would certainly be something to consider in a test of what can and cannot be a mechanism of memory in aphantasia. Someone else with aphantasia described drawing the shape with one's eyeballs as a way to "visualize" it without an image, and I also sometimes I do something like this.

I have been following stories on aphantasia with some delight since learning of its existence in the last year or so. It is my belief that no one has visual images in their head, and that those that think they do are mearly confused about what is happening with their brains as they recall an event or imagine a scene, object, or experience. For instance watch a few videos on change blindness. (Susan Blackman has a few compelling ones on youtube IIRC) Now think about a person imagining a scene in their head. I'm sure there may be a small subset of people who could keep all the facts of a busy street scene in their head. The majority of people though will simply believe they are seeing such a picture. (As people viewing a picture in change blindness experiments believe they are aware of all that is in their visual range.) If queried about particular features they may fill in the blanks as they go without ebven realizing that is what they are doing. I believe that even if people who state they can 'see' things in their head have visual sections of their brains light up it may just mean that the visual centers are online and contributing in some way to the illusion (or delusion if you will) of pictures in the head. As someone who would be labeled aphantasia I don't feel the need to prove a negative. Prove to me that other people actually do have a cartesian theater!

I was listing to the radio and it said picture a white horse ,under a tree by a brook I am 65 years old and i closed my eyes and it was just black . I ask my Husband if he could he said yes . I thought He was lying to me because i couldn't so I asked more people and they could . so after all these years i find out I am different . It sort of shocked me but if you never knew people could see these things you don't know your different til you hear about it

We have no idea, but they are color.

I don't think of myself as being mind blind because I "see"in concepts. I have come up with and designed several patents never seeing them in my mind's eye, but I completely understood them and knew what they would look like ad do. Never have seen anything in my mind's eye.

Hi, I am a 4th year student at the University of Edinburgh. My dissertation involves thinking about scenarios and objects, and the part aphantasia may play in this. If you are interested, please take a look at my questionnaire (should take less than 10 minutes!) and share it with anyone else who may be interested. You can find it here: https://edinburghppls.qualtrics.com/SE/?SID=SV_7aphPJ3t0Xb76sd

Yes we do. I have very vivid dreams sometimes. But with in a few minutes of waking, they are gone and I cannot visualise the event.

I found this post while searching for a connection between aphantasia and SDAM. Life long for both. No brain trauma that I'm aware of. Of course, I wouldn't remember if I had, would I? Anyway, I enjoyed the article.

Thanks for your comment, Daryl.

I think it's bogus. That is, people don't really have voluntary hallucinations, they're just "distracted from their actual vision", but not having the same sort of qualia-forming brain activity (unless perhaps they're about to sleep in a REM-like brain pattern). I find surprising that this concept is being taken for granted with no skepticism whatsoever, when there are longstanding debates on the nature of mental "imagery", with good arguments that it's not even really pictorial: Finally, Dennett (1969) presents two examples that seem to cause trouble for pictorialism and provide support for descriptionalism. The first example involves a striped tiger. (See also Armstrong 1968 for a related example involving a speckled hen.) Form a mental image of a tiger and then try to answer the following question: How many stripes does that tiger have? Invariably, the question cannot be answered; the mental images that we form typically do not contain that information. However, just as all tigers have a definite number of stripes, so too do all pictures of tigers. Thus, if mental images were pictorial, a mental image of a tiger should reveal a definite number of stripes. More formally, the objection to pictorialism that the striped tiger example poses can be stated as follows: Mental images can be indeterminate with respect to visual properties (e.g., the number of stripes on a tiger). Pictorial representations cannot be indeterminate with respect to visual properties. So, mental images are not pictorial representations. http://www.iep.utm.edu/imagery/#H1 While perhaps some people may have a harder time accessing some types of memory in a way that really constitutes some disability, I believe that the "phantasious"/volutional hallucination normal state is bogus. It seems like "repressed memories" in a way - real for those who thought they had them, but were just fooled into thinking they actually had them. There are plenty of well established perceptual illusions that would help creating the folk-psychological notion that we have these volitional hallucinations, in fact, we're actually immersed in a world of perceptions that are really illusory in many ways, like 98% of our field vision being actually "legally blind". But you wouldn't easily get it by relying just on self reports. The fact is that people are more "blind" than they are really aware of, and think they are not, with a hard time "believing" the illusions that made up normal perception are real. It wouldn't be surprising if this sort of unawareness was what happened with people who say they don't have aphantasia. Perhaps one should propose non-aphantasia it's really a mental manifestation of Anton–Babinski syndrome.

Now that I just read that, I recall a time when I experimented with micro dosing Psilocybin and that the results were as expected, but the one time I accidentally did slightly more, I in fact did not see visuals but did have audible hallucinations. Intense, but never a moment I thought it was real or could not tell when it was over.

Post a Comment

<< Home

Born in West Virginia in 1980, The Neurocritic embarked upon a roadtrip across America at the age of thirteen with his mother. She abandoned him when they reached San Francisco and The Neurocritic descended into a spiral of drug abuse and prostitution. At fifteen, The Neurocritic's psychiatrist encouraged him to start writing as a form of therapy.

View my complete profile

Previous Posts

- The Truth About Cognitive Impairment in Retired NF...

- What We Think We Know and Don't Know About tDCS

- Don't Lose Your Head Over tDCS

- Sleep Doctoring: Fatigue Amnesia in Physicians

- Everybody Loves Dopamine

- A Detached Sense of Self Associated with Altered N...

- Writing-Induced Fugue State

- The Brain at Rest

- Was I Wrong?

- How do you celebrate 10 years of an anonymous blog?

This is a paragraph of text that could go in the sidebar.

- Latest edition

- Collections

- Contributors

- For Writers

- Subscriptions

- Single editions

- Accessibility

Introduction

Reframing the thought experiment

Revolution in the head, featured in.

- Published 20210803

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-62-7

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction ‘Reframing the thought experiment’.

IT WAS ONLY recently that I learnt about aphantasia, a condition in which people cannot conjure up or visualise mental imagery. A friend explained that if she asked her children to imagine seeing an apple, they could describe exactly what they saw in their mind’s eye. She, on the other hand, could think about an apple, but could not bring an image – of an apple purchased, an apple eaten, an apple in a picture – to mind.

As someone who’s spent some time conjuring imaginary characters, places and events into being through fiction, not to mention trying to evoke passable versions of the real world in essays and journalism, this felt like a fascinating and fearsome proposition. In the current world, with its aspects of physical distance, separation and pre-industrial mobility, it presents as even more precarious.

I know it grabbed me as a concept because I find myself testing my internal visual acuity, springing small challenges on my own mind’s eye: can I picture this person? Can I picture this object? Can I recall and see this place, this painting, this creature? Tonight, I throw myself the challenge of Thomas More, author, lawyer, philosopher, executed in 1535 and canonised 400 years later.

And there he is, conjured up as Hans Holbein painted him in 1527: strong features, expensive trimmings, velvets and furs; a darkly direct gaze. I can conjure, too, the version created by Hilary Mantel to navigate hundreds of rich pages with Thomas Cromwell in Wolf Hall .

What’s this thought experiment about? It’s about imagination. It’s about the series of steps that links Thomas More to me here now – through history, through creativity, through the steps that his creations in his world have made and still make possible in mine, centuries later. Because tonight, I’m conjuring – through his image – the multitudinous atlas he made possible when he created a name for one perfect, unattainable nowhere.

The starting point of Sir Thomas More’s imagination matters here, as the progenitor of subsequent utopian creations. And Hilary Mantel’s imagination matters too because she returns More to the imaginative vocabulary, the imaginative populace of all her readers’ minds.

We can orient ourselves differently in this world – where we are and where we might be – by building out from each other’s imaginations. We need the place Thomas More imagined. We need the Thomas More Hilary Mantel imagined. We need the many disparate imaginations of each other, and then each of us can create new dot-points of no-places – or good-places – afterwards.

Remaking, transforming, reshaping and interpreting our own worlds, one train of thought at a time.

WE’RE WELL INTO the second year of this pandemic – at the time of writing this virus had accounted for at least 3.7 million lives around the planet, an almost unimaginable number of personal, familial, communal worlds remade. Early hopes that this moment of rupture might generate transformation or redress – an insistence on other systems, other shapes and futures – may have become tangled in the messy mechanics and logistics of vaccines, lockdowns, quarantines, separations, new precarities of daily life, but that makes them no less important. And there’s been no shortage of plans, proposals and suggestions for how to make the world anew. Part of Hey, Utopia! ’s mission is to explore different ways of conceiving of these as much as realising them, through the portals of the past, the present and the future; through new lenses, new frameworks, new fundamental questions.

The four editions of Griffith Review in 2021 set out to investigate different facets of sustainability: through resources, through mental wealth and wellbeing, through these utopias and – in November – through ideas of escape. Perhaps a current definition of sustainability has more licence, or greater necessity, to reflect not a sense of something ongoing – sustainability as maintenance – but the greater urgency for adaptation, change, evolution. Revolution. Of understanding other ways the world can be.

If imagination exists to understand the present and envision the future, as a special edition of Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene noted recently, ‘it is clear that who imagines our future, and what kinds of processes and inputs are used matters greatly to whether a transformation moves us toward addressing sustainability and justice.’

THESE STORIES WILL introduce a variety of proposed utopias – past, present and future – and some means for working towards others, alongside some of their inevitable dystopian cousins. This part of the world has had utopian labels applied to it in different ways at different times, from northern-hemisphere daydreams of a Great Southern Land to Samuel Butler’s fictional country Erewhon, brought forth from the vantage point of a sheep farm in New Zealand in the mid-nineteenth century. Australia itself has been presented as utopian – Tasmania, in particular. The realities hidden beneath these labels make clear the urgent necessity of shaking free from their utopian presumptions. In this, several writers here look towards the generous invitation of the Uluru Statement From the Heart as the most critical way for Australia to work towards a new relationship with itself. And this underscores the importance of reframing and reckoning with the past and its ongoing legacies to create a new future.

From worlds conceived for and by children, from the power of changing the world by recalibrating the measurements taken from it in areas as disparate as science, poverty, manufacturing and management, and from consideration of futures now past – particularly in distant sci-fi and the nostalgia of decades of world expos – all these voices intersect in different ways with how we imagine change and transformation, and how we ground what we imagine in the real world. They proffer not only possibilities but also an insistence on the importance of understanding that any newly made now is just the next transitory moment in which we find ourselves, heading towards a next step forward.

A suite of essays – by Julianne Schultz, Justin O’Connor, Kristen Rundle and Anna Yeatman – grew from conversations with Julian Meyrick around Thomas Piketty’s call in Capital and Ideology for a ‘just society’, a set of ‘sober, practical proposals’ that underscore one critical insight: not only must something be done to change the world’s direction, it can be. Their raft of words also launch new revisions, reflections and navigations of what Australia has been, is and may yet be, and I’m very grateful for Julian’s enthusiasm, vision and generous assistance through their editorial journey.

In these pages, alternate histories spring from creative time travel; alternative futures spring from an insistence on radical change – in the evolving on-the-ground intersections of sports and trans-athletes as much as in policy, law, governance and economics. Perhaps the very act of asking ‘what if?’, of role-playing ‘as-if’ alternatives, can lead to transformation. Perhaps the very act of asking ‘if not now, when?’ can alter the timescale for change. Even the pandemic can be recast to reveal moments of epiphany, recalibration, even creativity made possible – and financially supported – in the depths of its grip.

Each voice, each perspective also speaks to the ground-truth set out by American writer, teacher and religious scholar Sarah Sentilles: ‘When we make art – sentence, loaf of bread, garden, painting – we exercise the muscles we need to remake the world. We remember it’s possible to create something new.’

This edition of Griffith Review marks a great change in its own world. After eighteen years – and sixty-two editions as editor (2003–2018) – Julianne Schultz will leave Griffith University this September, stepping down as Griffith Review ’s publisher. Griffith Review grew from and depended on Julianne’s vision: under her leadership, the publication broke stories, ignited conversations, changed political directions, discovered new voices. A touchpoint of thought leadership and the ever-changing zeitgeist, it changed the shape of Australia’s literary landscape. Julianne is, as The Canberra Times once said, the ‘ultra-marathoner of Australian cultural life’, and it’s a privilege to work out from the extraordinary foundations she created, expanded and saw thrive. We’re grateful for the chance of having her words in her last edition, and excited to see which races she runs next.

THE PINK FLAMINGOS on this cover are from Melbourne artist Kate Ballis’s Infra Realism project, which blasts segments of the world into new being with one bright overlay. What Thomas More would make of that brilliant transformation, that evocation of another world, I’m not sure. How he’d imagine and see it – across the space between his time and ours – is an intriguing thought experiment in itself.

And those who live without actual internal vision, who live inside an aphantasic blank? My friend who cannot conjure up an apple has one of the broadest, sharpest, clearest, most imaginative and analytical ways of thinking, exploring, questioning and understanding that I know. Even without the pictures. Which is perhaps another way of saying there are no excuses then.

9 June, 2021

Share article

Tweet Share Share Pin 0 Shares

Subscribe to great writing

Access starts at just $6 per month. Print and digital options to suit every budget!

More from author

Between different worlds

Introduction Antarctica offers windows into many different worlds...

More from this edition

Facing foundational wrongs

Essay ROMAN QUAEDVLIEG STANDING tall in his smart black suit – medals glistening, insignia flashing – looked every bit the man-in-uniform from central casting when he stood...

Lost utopias

Picture Gallery

Home, together, a family

Memoir APPARENTLY, THE STEROIDS saved Charlotte’s life. Taking Charlotte out so early definitely saved Elizabeth’s life. The placenta was killing both of them: starving Charlotte...

What Really Happened with the Apple?

Sir isaac's most excellent idea, the center of mass for a binary system, two limiting cases, circular velocity and geosynchronous orbit, v circ = (gm/r) 1/2, open and closed orbits, escape velocity, v es = (2gm/r) 1/2, weight and the gravitational force, mass and weight, newton's derivation of kepler's laws, v circ = (gm/r) 1/2 = (2 pi r)/ p, (gm) p 2 = 4 pi 2 r 3, newton's interpretation of kepler's laws, g(m s + m p ) p 2 = 4 pi 2 r 3, g m s p 2 = 4 pi 2 r 3.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

One thought experiment got stuck in my mind (and as a non-physicist, I paraphrase from the show): An apple is placed in a closed box (in theory nothing can come out or in the box). Over time the apple decays, after more time the apple has become dust, years and years later the remaining chemicals get very hot, a long long time later the ...

It asks you to close your eyes and imagine an apple, then judge the clarity of the apple based on the scale of 1 - 5. If you score a 5, if you cannot see any apple at all but know you are thinking of an apple, then you might have a condition called aphantasia. The Aphantasia Network defines the condition as "the inability to visualize.

Imagine a box with an apple inside, locked up tight so nothing can get in or out. As time ticks away, the apple starts to change. It goes from a tasty fruit to tiny specks of dust. After a super-duper long time, these specks warm up and stick together like a giant space cotton. Eventually, the box is filled with itsy-bitsy pieces and bright light.

Spread. On February 3rd, 2023, Twitter user @stinkykatie posted the same apple visualization chart, writing, "if you close your eyes and try to picture a red apple, which one do you see? I see number 1 in full color, as vivid and detailed as a 4k video," garnering over 18,400 likes and 14,000 quote-tweets in a week.

The apple can decay without the hadrons decaying, but I think that's missing your point.. The "apple in a box" thought experiment is more of a demonstration of the interplay between statistical mechanics and entropy. Newton's The Second Law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of a closed system increases with the progress of time. That's the apple rotting away--the moisture and gases in ...

The apple will decay etc etc but because there are a finite number of possible states for the contents in the box, it must eventually reach a state it was in before (all good up to here) and so it will eventually become an apple again. ... - Thoughts experiments like these can be very revealing about how the universe work and lead to useful ...

The apple visualisation test raised questions about how people dream and whether every brain dreams in images or just feelings. Which, honestly, has just stressed me out now because if I don't visualise things, then my dreams could just be a big, fat lie. Omg this is insane to me! I'm a 1 and when I close my eyes it's like watching a film!

— Ed Berry (@ed_berry) May 3, 2016 Footnote 1 Aphantasia seems bizarrely overrepresented in Galton's cronies. Here's his explanation: My own conclusion is, that an over-readiness to perceive clear mental pictures is antagonistic to the acquirement of habits of highly generalised and abstract thought, and that if the faculty of producing them was ever possessed by men who think hard, it is ...

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction 'Reframing the thought experiment'. IT WAS ONLY recently that I learnt about aphantasia, a condition in which people cannot conjure up or visualise mental imagery. A friend explained that if she asked her children to imagine seeing an apple, they could describe exactly what they saw in…

Again, we expect the apple to be accelerated toward the ground, so this suggests that this force that we call gravity reaches to the top of the tallest apple tree. Sir Isaac's Most Excellent Idea ... This can be illustrated with the thought experiment shown in the following figure. Suppose we fire a cannon horizontally from a high mountain; the ...